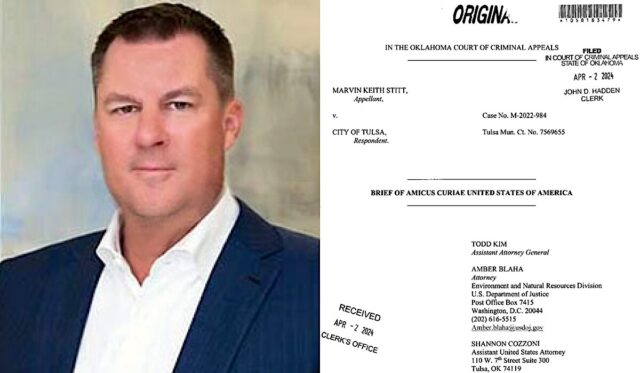

The United States has filed an amicus brief with the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals supporting petitioner Marvin Keith Stitt, a high-profile development that marks the first time the federal government has weighed in on major Indian law decisions coming from the state’s top criminal court since December.

Stitt, a Cherokee Nation citizen and Gov. Kevin Stitt’s brother, is challenging a charge of aggravated speeding brought against him in Tulsa Municipal Court after he was issued a citation within the Muscogee Nation Reservation in Tulsa.

RELATED

A tale of two brothers: Kevin Stitt fights to limit McGirt ruling, Keith Stitt uses it to challenge ticket by Tristan Loveless

Asked his thoughts on the United States submitting a brief in support of his brother’s case, Gov. Kevin Stitt found the odd circumstances amusing.

“It’s hilarious,” Stitt said. “But its back to what I’ve been saying. This is what I’ve been trying to tell people: Do you want a two-tiered system based on race? We’ve got Indians, and an Indian, remember, looks like me. It’s my brother in his Range Rover (…) driving across Tulsa — speeding — and the Tulsa Police Department wrote him a ticket, and all five tribes agreed with him that he didn’t have to pay the ticket (to the city).”

The governor scoffed at speculation that he and his brother have coordinated the unusual court case to prove a point about the July 2020 McGirt v. Oklahoma U.S. Supreme Court decision, which functionally affirmed eastern Oklahoma as a series of Indian Country reservations where only the federal government and tribes can prosecute tribal citizens accused of committing crimes.

“What’s funny is all the tribes are all having to support my brother, Keith,” Stitt said with a laugh. “I did not know he was going to [file the suit].”

According to constitutional law scholars like Erwin Chemerinsky, current U.S. Supreme Court precedent considers Indian status to be a political relationship — similar to citizenship — between a tribal government and its members, not a racial category.

Feds say McClanahan controls, not Bracker

As outlined in the new legal filing, the United States’ position in Stitt v. Tulsa is simple: Oklahoma lacks criminal jurisdiction over Native Americans in Indian Country.

The 30-page brief (embedded below) was filed Tuesday and focuses almost entirely on that argument, devoting little time to the “Bracker balancing test” analysis requested by the court.

The Bracker balancing test originates from Thurgood Marshall’s opinion in the 1980 U.S. Supreme Court case White Mountain Apache Tribe v. Bracker. The test is applied to determine whether federal law has preempted state law regulating non-Indians on a reservation by examining the nature of the federal, state and tribal interests at stake and trying to balance each side’s interests.

Notably, the U.S. Supreme Court has never applied the Bracker test to an Indian in Indian Country.

RELATED

Future ‘Bracker’ test teased as appellate court affirms Wyandotte Reservation 4-1 by Tristan Loveless

In Keith Stitt’s appeal, the United States’ brief focused on Oklahoma lacking criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens in Indian Country for 29 of its 30 pages. One page was devoted to arguing that the Bracker test should not be applied, with only a footnote to the application of the Bracker test.

Attorneys for the United States argued that under current U.S. Supreme Court precedent, the Bracker test is inappropriate to apply to a tribal citizen in Indian Country. Instead, the Department of Justice attorneys wrote, the court should apply a test from the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court case McClanahan v. Arizona State Tax Commission.

In the McClanahan case, Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote a unanimous opinion that held Arizona lacked jurisdiction to levy state income tax on Navajo citizens residing on the reservation and earning their income entirely from tribal sources, a decision relevant to the current Stroble v. Oklahoma Tax Commission case pending before the Oklahoma Supreme Court.

“McClanahan and the cases preceding and following it establish a general rule against state jurisdiction over Indians for on-reservation activity except as authorized by Congress,” the U.S. attorneys wrote in the Stitt-case brief filed Tuesday. “The state of Oklahoma lacks jurisdiction to prosecute this case.”

While the United States argues that the Bracker test is inapplicable, recent decisions by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals have indicated that a majority of that court’s judges are open to using the test to determine if the state has criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens in Indian Country.

Brett Chapman, the attorney representing Keith Stitt, said the DOJ’s amicus brief illustrates why his client’s case matters.

“The interest taken by the federal government in the case is another indication of the importance of these issues, not only to the parties to this case, but others not party to the case,” Chapman said.

Cases challenge Tulsa’s criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens

When it was filed Tuesday, the motion became the latest major development in Tulsa’s effort to continue exercising criminal jurisdiction in municipal courts over tribal citizens following the McGirt decision. Among other issues, the adjudication of traffic tickets by cities and towns is a significant source of revenue for Oklahoma municipalities.

Last year, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals’ Hooper v. Tulsa decision held that the Curtis Act no longer applied to Tulsa, invalidating the city’s argument that the Curtis Act provided the city criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens. The Hooper case was then sent back to the U.S. Northern District of Oklahoma where it was dismissed.

RELATED

Muscogee Nation sues City of Tulsa in latest jurisdictional fight

by Joe Tomlinson

But two other major cases — one in the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals and another in the U.S. Northern District of Oklahoma — are pending on the issue of municipal courts in Oklahoma exercising criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens within reservation boundaries.

In state court, the Keith Stitt speeding ticket case is pending, and the arguments have narrowed to center on whether the Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta decision allows for the state of Oklahoma to exercise criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens. The case initially focused on the Curtis Act, but supplemental briefings after the Hooper decision centered on whether the “Bracker balancing test” can be applied to tribal citizens.

In federal court, the Muscogee Nation sued the City of Tulsa seeking a declaratory judgment that the city lacks criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens within the Muscogee Nation Reservation.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

Tribes file notice, City of Tulsa objects

Two days before the federal government submitted its request to file a brief in the Keith Stitt speeding ticket case, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Choctaw Nations submitted a joint “notice of supplemental authority” on Feb 5 addressing the Hooper decision and a state court case referred to as the Crosson decision.

The tribes’ notice argued that the 10th Circuit’s Hooper decision settled the Curtis Act argument and that the Crosson decision held that the application of the Bracker test was a factual inquiry for the district court and should not be applied for the first time by the appellate court.

Ten days later, on Feb. 15, the City of Tulsa submitted a motion asking to strike the tribes’ notice of supplemental authority and to reject the United States’ motion to file a brief. Tulsa argued “this case is well past the 11th hour” and “that the [U.S. Attorney’s Office] is unaware of a highly publicized Indian Country jurisdiction case filed in the same federal courthouse where it operates is not a valid reason to delay here.” (The federal government submitted its motion to file an amicus brief Feb. 7, saying the DOJ “first learned about this court’s supplemental briefing request in late January,” around the time NonDoc published an overview of the case.)

The City of Tulsa’s brief also criticized the U.S. Attorney’s Office for not working with the city to help prosecute burglary cases and listed law enforcement cooperation commissions from which the city has the authority to withdraw:

Although the United States is supposed to maintain exclusive criminal jurisdiction over crimes committed by Indians when such crimes are enumerated in the Major Crimes Act, federal law enforcement agencies are not the primary investigators of such crimes within the City of Tulsa; Tulsa Police Department conducts the investigations and provides the prosecutors packets to the USAO, and then the federal law enforcement officers sometimes conduct follow-up investigations such as obtaining search warrants for cellar phones and so on.

Importantly, although many Tulsa Police Officers have federal commissions with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Federal Bureau of Investigation, and other agencies, the city has agreed to investigate these crimes which are the responsibility of the federal government through a written agreement and may withdraw from that agreement at any time giving 30 days’ notice just as the city can withdraw from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and [Muscogee (Creek) Nation] cross-deputization agreements with 60 days’ notice and Cherokee Nation cross-deputization agreement with 30 days’ notice. The USAO does not even prosecute all the Major Crimes (Act) cases presented by Tulsa police and continues to decline a significant number of cases for prosecution including almost all burglaries. As such, the USAO is certainly not going to prosecute the misdemeanor and traffic citations filed in the municipal court.

Read the federal amicus brief here

Loading...

Loading...