While Gov. Kevin Stitt has made defending state sovereignty a major goal of his administration since the McGirt v. Oklahoma decision, his older brother — Marvin Keith Stitt — is the appellant in a case before the state’s highest criminal court that argues tribal sovereignty prohibits cities from adjudicating traffic tickets issued to Indigenous people within reservation boundaries.

The Stitt brothers’ difference in legal positions highlights Oklahoma’s major disagreements about how to respond to the McGirt decision, which functionally affirmed a series of Indian County reservations in eastern Oklahoma. Gov. Stitt has made championing state interests his primary response to the landmark decision, while tribal governors and chiefs have pushed to expand their nations’ sovereignty. Despite the positions of his brother, Keith Stitt has found himself defending the expansion of tribal authority through litigation stemming from a 2021 speeding ticket.

The brothers Stitt are citizens of the Cherokee Nation. Keith Stitt is an attorney and the founder of Colonial Title, a title company with offices in Tulsa and Owasso. Before running for governor, Kevin Stitt founded a mortgage company that has now become a bank.

While driving his green Range Rover down U.S. Highway 75 at approximately 78 mph in February 2021, Keith Stitt was pulled over by a Tulsa police officer in a 50-mph zone, according to court records. The officer approached Keith Stitt’s vehicle and asked for his driver’s license. He provided the officer both his Oklahoma license and his Cherokee Nation citizenship card before being issued a ticket for speeding between 16 and 20 mph over the speed limit.

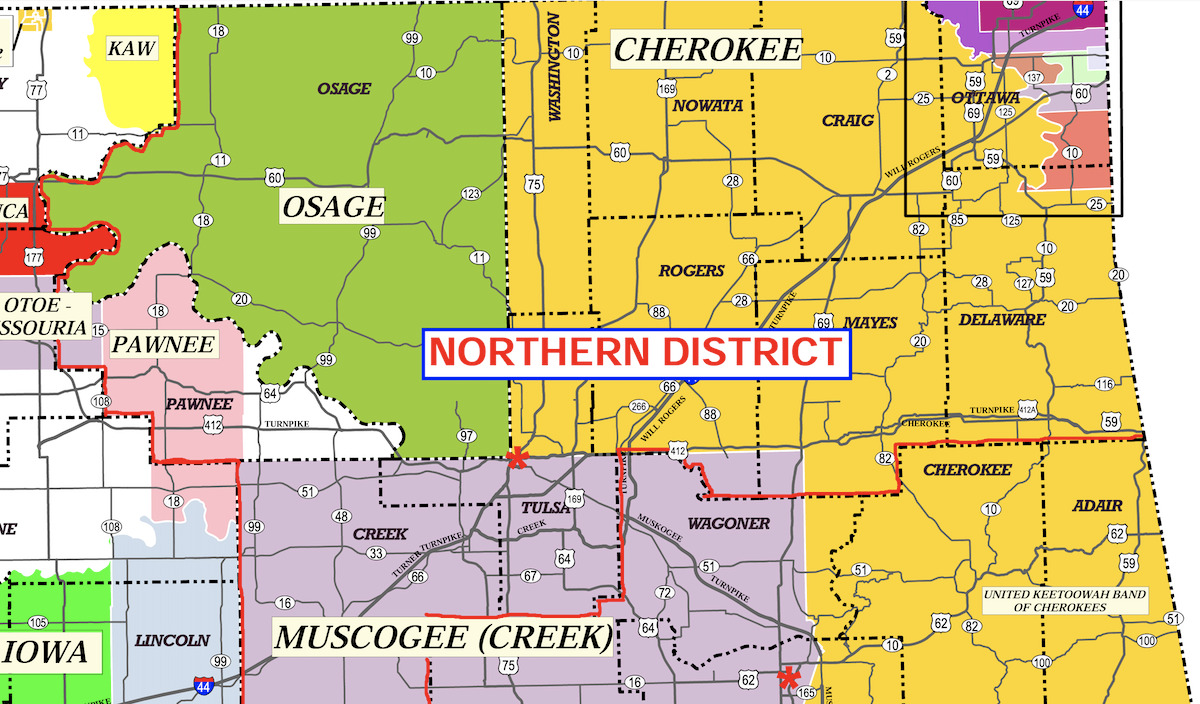

An attorney and tribal citizen, Keith Stitt was aware that he was driving in the Muscogee Nation Reservation, and he challenged the officer’s issuance of the ticket, according to court documents.

“Isn’t this my get out of jail free card?” court filings say Keith Stitt asked in reference to his tribal citizenship card.

The traffic ticket case was sent to Tulsa Municipal Court, and between February 2021 and June 2022 Judge Mitchell McCune rejected Keith Stitt’s motions to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. Keith Stitt appealed those rulings, and now Stitt v. Tulsa asks the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to determine whether Oklahoma municipalities within Indian Country reservations possess criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens.

The appeal pits a Stitt supported by tribal governments against the City of Tulsa, which has argued that either the Curtis Act or the Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta decision provides the city with criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens.

The lawsuit could help settle the question of which governments have criminal jurisdiction to adjudicate traffic infractions committed by tribal citizens within reservation boundaries. Owing to the McGirt decision, tribal governments of the Muscogee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Quapaw, Peoria and Miami nations possess criminal jurisdiction over crimes committed by tribal citizens within their reservations.

Tribal governments maintain that the state of Oklahoma and its subdivisions like the city of Tulsa lack criminal jurisdiction over crimes committed by tribal citizens in Indian Country.

“The views of the Cherokee Nation on this issue are clear and consistent: history, the law, and the constitution all confirm that tribes have inherent sovereign authority to exercise criminal jurisdiction over Indian citizens on their reservations, and the state does not,” Cherokee Nation Attorney General Chad Harsha said in a statement when asked about Stitt v. Tulsa.

Some cities, such as Tulsa in the Hooper v. Tulsa case, have argued that their municipal courts retain criminal jurisdiction over tribal citizens and continue to prosecute traffic infraction cases against tribal citizens within reservation boundaries. The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled last year that the Curtis Act no longer applied to Tulsa, but the dispute is ongoing.

Another pending lawsuit in federal court, Muscogee Nation v. Tulsa, also could settle the jurisdictional question. A declaration from a federal court that federal law prevents cities from exercising criminal jurisdiction over Native Americans could settle the question for state courts.

Kevin Stitt’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment about his brother’s legal challenge. Muscogee Nation press secretary Jason Salsman said Muscogee leaders are not commenting publicly on the pending case. Likewise, City of Tulsa communication director Michelle Brooks said the city “does not comment on pending litigation.”

Before appeal, city increased charge against Keith Stitt

McCune, the Tulsa municipal judge, denied two motions to dismiss Keith Stitt’s traffic ticket. On June 16, 2022, city prosecutors amended his charge to the higher crime of “aggravated speeding,” which includes a fine of up to $500 and up to 10 days in the city jail. The heightened charge was approved after his attorney notified the court that he intended to appeal McCune’s earlier decisions.

Brett Chapman, Keith Stitt’s attorney, worried that the amended charge could have had a “chilling effect” on his client, while noting the city had “legal authority” to take the action it did.

However, Chapman also said his client “remained resolute” in his decision to challenge the decision despite the higher charge and possibility of jail time. Chapman also indicated that if the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals sided with Tulsa, he would appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

‘Just another resource theft from Indigenous people’

Beyond sovereignty standards, this traffic ticket jurisdictional conflict is also fueled by the revenue from issued citations. Prior to McGirt, Tulsa and other cities collected all revenue from the tickets their officers issued to tribal members.

Since McGirt, tribal courts have been handling more and more of these cases and have been collecting ticket revenue. Chapman said Tulsa’s attempt to hear traffic tickets for tribal citizens in municipal court is part of a long history of resource theft from Indigenous people.

“They’re stealing revenue. This is just another resource theft from the tribes,” Chapman said. “First, it was land with the Curtis Act, and now it’s ticket revenue.”

When heard in state courts, citations for speeding between one and 10 mph over the speed limit have their revenue divided between various state services, outlined in a statute, including:

- The court hearing the case;

- The District Attorneys Council Revolving Fund;

- The Oklahoma Court Information System Revolving Fund;

- The county sheriff’s service fee account;

- The attorney general’s victim service unit;

- The child abuse multidisciplinary account;

- The Council on Law Enforcement Education and Training Fund;

- The Automated Fingerprint Identification System maintained by OSBI;

- The forensic science improvement revolving fund of OSBI;

- The court clerk’s revolving fund; and

- The district court revolving fund.

Beyond litigation, however, another route exists to address cities’ concerns about lost revenues. Since the McGirt decision, the Cherokee Nation has entered into several revenue-sharing agreements with city governments to share citation fines paid by tribal citizens.

In an Oklahoma Bar Journal article published last year, Cherokee Nation Deputy Attorney General Chrissi Ross Nimmo argued for compacting between tribes and municipalities to resolve revenue concerns.

“As shown by the cross-deputization agreements and the municipal ticketing [agreements], if towns and cities within the Cherokee Nation are willing to come to the table and have a discussion, there are not many problems that cannot be solved together,” Nimmo wrote.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

Familiar arguments made in appellate briefs

In November 2022, Stitt v. Tulsa was officially filed with the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals. Since then, two waves of briefs have emerged: an initial set of filings and a supplemental set after the Hooper decision.

Most of the initial briefs focused on arguing over Section 14 of the Curtis Act’s meaning and mirrored the arguments made in federal court during the Hooper case. However, most of these arguments were likely rendered moot by the U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision holding that Section 14 of the Curtis Act was no longer applicable to Tulsa.

Nonetheless, in its supplemental briefs, the City of Tulsa has continued to argue the Curtis Act applies. If the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals sides with Tulsa on the Curtis Act argument, there would be inconsistent rulings interpreting the act from the highest state criminal court in Oklahoma and from the 10th Circuit federal court, which would substantially increase the likelihood of the U.S. Supreme Court intervening. In August 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court denied a petition to review the 10th Circuit’s Hooper decision.

Tulsa also argued in its supplemental briefing that the city, through the state, possesses concurrent jurisdiction to charge Keith Stitt under the Castro-Huerta decision and the “Bracker balancing test.” The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals has signaled in recent cases that “future cases” will decide the applicability of the Bracker balancing test to cases involving Native Americans in Indian Country. So far, the U.S. Supreme Court has only used the Bracker test on cases involving non-Native Americans in Indian Country, and the court has never applied the test to a Native American in Indian Country.

Tulsa is supported in its case by an amicus brief from the Oklahoma Association of Municipal Attorneys. OAMA President Beth Anne Childs has also represented Tulsa during the lawsuit.

Chapman’s theory: Tulsa never had criminal jurisdiction over Native Americans under the Curtis Act

If you ask Brett Chapman whether the Curtis Act ever provided criminal jurisdiction over Native Americans in Indian Territory, he says the answer is clear: No.

“Back in the day, they used to have these elaborate type of common law pleadings,” he said. “But today it’s all statutory.”

Since Oklahoma statehood in 1907, the constitutional protections for people charged with crimes have grown substantially through both legislation and court decisions. The practice of criminal law has fundamentally changed in the past 117 years, and Chapman argues that prior to these changes municipal ordinance violations in Indian Territory were treated as civil cases instead of criminal cases.

In towns recognized under the Curtis Act, the municipal courts were mayors’ courts where the town mayor would also serve as the municipal judge.

“I think that Congress clearly knew that that was not criminal in nature because they provided absolutely no appellate route on the criminal (side),” Chapman said. “They never moved over the criminal appeals section for the mayors’ courts.”