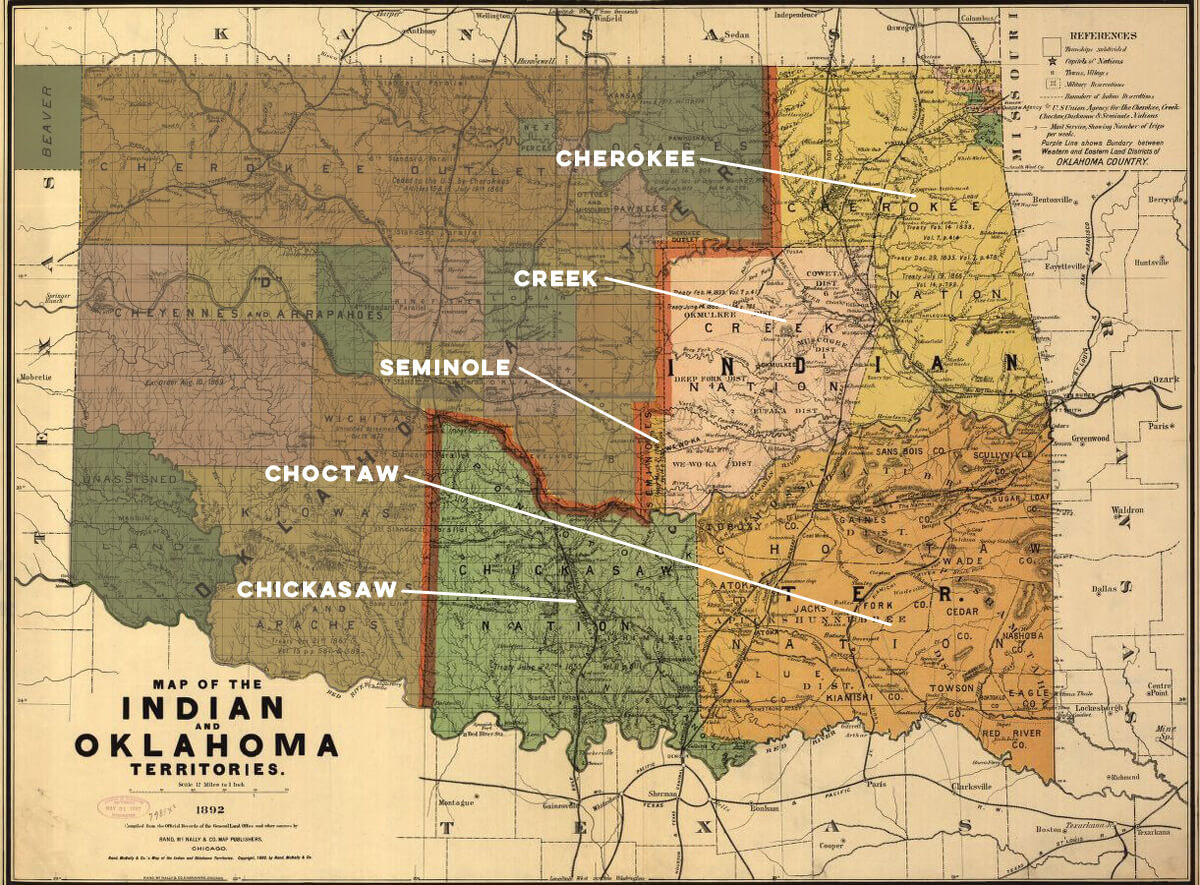

Oklahoma retains subject matter jurisdiction over crimes committed by Indigenous people in Indian Country, according to a recent decision from the state’s highest criminal court that could draw legal challenges from tribal citizens or nations in federal court.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals released its 3-2 decision in Deo v. Parish on Dec. 14. Written by Judge William J. Musseman, the majority decision held that Oklahoma retains subject matter jurisdiction — a procedural prerequisite stipulating that a certain court has the authority to hear a case — over a second-degree burglary case against Billy Zane Deo, a citizen of the Muscogee Nation.

The new decision effectively flips the burden of proof on defendants trying to have state charges dismissed based on Indian status in eastern Oklahoma, which was affirmed as a series of Indian Country reservations in 2020. After the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, state prosecutors generally had to prove subject matter jurisdiction over Indian defendants for a case to proceed. Now, judges must allow cases to continue until defendants raise an objection based on personal and territorial jurisdiction.

Eliminating lack of subject matter jurisdiction as a defense also opens the door to Indian defendants to be prosecuted in state court if they fail to raise their personal and territorial jurisdiction defenses. Unlike subject matter jurisdiction, objections based on other forms of jurisdiction are waived if not raised in the early stages of the criminal case.

Issued the day before a federal court’s dismissal of Hooper v. City of Tulsa, the Deo decision lands among other recent rulings from the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals concerning criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country. Tribal leaders responded to the decision with criticism and an eye to federal law that could form the basis for an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Arrested before McGirt, but not convicted, Deo lingered in legal limbo

Deo pleaded guilty to second-degree burglary in August 2018 and received a seven-year deferred sentence. That December, he was charged with grand larceny and knowingly concealing stolen property in Okfuskee County District Court.

In January 2019, he pleaded guilty in exchange for admission to drug court, a specialized venue for handling drug offenders focused on rehabilitation. A month later, prosecutors filed to remove him from drug court, but that motion never received a ruling. In April 2019, he was charged in Okmulgee County District Court with false personation. After another plea, Deo was sentenced to 10 years in prison to run concurrently with his Okfuskee County cases.

In 2012 and 2022, after the McGirt decision, Deo’s attorney filed for dismissals by claiming the state court lacked subject matter jurisdiction. Judges in Okfuskee County and Okmulgee County denied the dismissals, and Okfuskee County District Judge Lawrence Parish’s ruling was appelaed to the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals. Now, with that court’s Dec. 14 decision, Deo’s case heads back to Okfuskee County District Court for further proceedings.

Department of Corrections records indicate Deo was discharged from the state prison system in May. DOC spokeswoman Kay Thompson said Deo was transferred an to Okfuskee County deputy sheriff, but records indicate Deo now has outstanding warrants related to his case being remanded to district court for further proceedings.

In their Dec. 14 decision, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals distinguished three types of jurisdiction in its opinion: personal, subject matter and territorial.

Territorial jurisdiction involves the area controlled by a government within which its laws are in effect. Personal jurisdiction refers to whether a court has jurisdiction over the person involved in the case, which usually means that the person has “minimum contacts” with the territorial jurisdiction. Subject matter jurisdiction limits the type of case that can be heard by a court. For example, bankruptcy courts are special courts with subject matter jurisdiction over bankruptcy cases.

Musseman: Bracker balancing applies to personal, territorial jurisdiction

The Deo decision holds that Oklahoma courts’ subject matter jurisdiction over crimes committed by Indians in the state is not preempted by federal law and that objections to jurisdiction based on McGirt v. Oklahoma stem from personal and territorial jurisdiction. It also found that the “Bracker balancing test” is only necessary if personal and territorial jurisdiction are at issue.

Deo’s attorney had failed to argue personal or territorial jurisdiction issues earlier and waived the objections by failing to raise them, the appellate court found.

“Therefore, Bracker balancing is only triggered once the territorial and personal jurisdiction components are satisfied and is not impacted by the type of controversy. As a result, Bracker balancing does not operate to preempt Oklahoma district court’s subject matter jurisdiction,” wrote Musseman, who was joined by presiding Judge Scott Rowland and Judge Gary L. Lumpkin, who both wrote concurring opinions.

Dissenting judges say majority ‘bypassing McGirt’

A dissenting opinion by Judge Robert L. Hudson argued that the Deo decision was sidestepping McGirt and ignoring the Bracker test.

“The majority opinion rebrands our consideration of Indian Country jurisdictional challenges based on McGirt v. Oklahoma from subject matter jurisdiction under state law to matters involving only personal and territorial jurisdiction — thereby bypassing McGirt,” Hudson wrote.

Judge David B. Lewis also wrote a dissent, forcefully arguing that “states have no jurisdiction of crimes committed by Indians in Indian Country unless it is expressly conferred by Congress.”

“‘No jurisdiction’ means no jurisdiction, no sovereign authority to act,” Lewis wrote. “Congress has never conferred criminal jurisdiction over Indians in Indian Country on the State of Oklahoma.”

Application of Bracker balancing test left ‘for future cases’

The Bracker balancing test originates from Thurgood Marshall’s opinion in the 1980 U.S. Supreme Court case White Mountain Apache Tribe v. Bracker. The test is applied to determine whether federal law has preempted state law regulating non-Indians on a reservation by examining the nature of the federal, state and tribal interests at stake and trying to balance each side’s interests.

The Bracker test was brought new life by the June 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, where the court used the test to determine that Victor Manuel Castro-Huerta, a non-Indian, could be prosecuted by the state of Oklahoma for a crime against a tribal citizen committed in Indian Country.

Since Castro-Huerta, attorneys for Oklahoma and the City of Tulsa have argued that the Bracker test should be applied to determine if the state has jurisdiction to prosecute Indians for crimes committed in Indian Country.

Applying a Bracker analysis to a tribal citizen in Indian Country would stand as a new development in Indian law, and the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals stopped short of doing so in Deo v. Parish.

“To the extent the state has the power to prosecute Indians in Indian Country, that will be for future cases to decide,” Musseman wrote in a footnote.

Oklahoma’s subject matter jurisdiction after the Deo decision

The Deo decision immediately affects Indian defendants who are asking judges to dismiss their pre-McGirt pleas in cases that have not had a final judgment. Often, those criminal cases involve deferred sentences. Now, such defendants cannot seek relief by arguing that Oklahoma lacks subject matter jurisdiction, one of the few legal defenses that could have been brought up at any time.

The Deo decision also marks the first time an Oklahoma appellate court has asserted subject matter jurisdiction over crimes committed by Indians in Indian Country post-McGirt. In support of their decision, the court referenced a 1945 case, Ex parte Wallace, where it had held that an Oklahoma court had subject matter jurisdiction over a first-degree rape case involving a tribal citizen in Indian Country.

The court also made the rare decision to overturn parts of three decisions inconsistent with the new opinion, naming Magnan v. State, Hogner v. State and McClain v. State as partially overruled in a footnote.

Since the decision was made by Oklahoma’s highest criminal court, any request to appeal it would have to be granted by the U.S. Supreme Court. The decision is only binding on Oklahoma state courts and does not affect other states. It is unclear whether any party will seek an appeal.

Crosson, Deo decisions expand state authority in Indian Country

The Deo decision follows another Court of Criminal Appeals opinion, State v. Crosson, which held that state judges must issue an arrest warrant for a tribal citizen in Indian Country if there is probable cause for an arrest warrant.

RELATED

Precedential prosecution: How Brayden Bull ended up in federal, state and tribal courts by Tristan Loveless

Read together, the opinions mean that state judges must issue arrest warrants for Indigenous defendants when prosecutors present probable cause and that state courts have subject matter jurisdiction to hear those criminal cases.

The decisions flip the burden of proof on the question of criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country. Prior to the decisions, judges were dismissing cases because the state had to prove the court had jurisdiction before the case could proceed. After the decisions, the burden to prove that the state lacks jurisdiction shifts to defendants in the form of affirmative defenses they either raise or waive in their initial filings.

However, neither the Crosson case nor the Deo decision holds that the state of Oklahoma has criminal jurisdiction over Indians in Indian Country. Indigenous defendants accused of crimes within tribal reservation boundaries can still move for dismissal based on the state lacking personal and territorial jurisdictions.

Nonetheless, the new rulings do represent a notable expansion of state authority in Indian Country.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

Tribal leaders criticize Deo decision

As reported by the Tulsa World Muscogee Nation press secretary Jason Salsman and Cherokee Nation Attorney General Chad Harsha issued statements criticizing the Deo decision.

“It is well established in federal law that the state lacks criminal jurisdiction over Indians in Indian Country, and it was Oklahoma’s illegal prosecution of Indians in a reservation that led to the McGirt decision,” Harsha said. “Given this history, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals decision today is disappointing and we will carefully review it.”

Salsman decried “false rhetoric” surrounding criminal jurisdiction in eastern Oklahoma, and he hinted at the ruling’s potential incongruity with federal law.

“The legal gymnastics used to apply Castro-Huerta in this decision makes it clear that some courts in Oklahoma may be misinformed, embracing the false rhetoric from the political campaign to overturn the McGirt decision, and in a manner contrary to well-established federal law,” Salsman said.

A spokeswoman for Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt’s office did not respond to a request for comment prior to the publication of this story.

(Update: This article was updated at 12:30 p.m. Wednesday, Jan. 10, to include additional information provided by the Department of Corrections about Deo’s release from prison. It was updated again at 3:05 p.m. Thursday, Jan. 11, to reflect different information provided by DOC.)