The Wyandotte Nation has become the 10th tribal government in Oklahoma to have its reservation affirmed by a court since the McGirt v. Oklahoma decision in 2020.

The Wyandotte Reservation in Ottawa County continues to exist, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ruled in a 4-1 decision March 7. Other tribes whose reservations have been recognized include: the Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation, Choctaw Nation, Seminole Nation, Muscogee Nation, Quapaw Nation, Peoria Tribe, Miami Tribe and Ottawa Tribe.

While most reservations in Oklahoma were ruled never to have been disestablished, the Wyandotte Reservation is slightly different. According to the decision in State v. Fuller, the reservation was first established by treaty in 1867 and later explicitly disestablished by Congress when the tribe’s recognition was terminated by legislation in 1956. Crucially, Congress repealed the termination legislation in 1978 and reinstated federal recognition.

Since the 1978 act of Congress restored “all rights and privileges” to the Wyandotte Nation that were terminated in 1956, appellate court judges found that the 1978 law restored the Wyandotte Reservation and upheld a district court ruling that found the reservation still exists today. The court previously reached a similar decision when it upheld the Ottawa, Peoria and Miami reservations in State v. Brester.

“We find the district court’s determination that the Wyandotte Reservation has not been disestablished by Congress and remains Indian Country for purposes of federal criminal law was not an abuse of discretion,” wrote Presiding Judge Scott Rowland.

Wyandotte Reservation recognized, court disagreements simmer over Bracker test

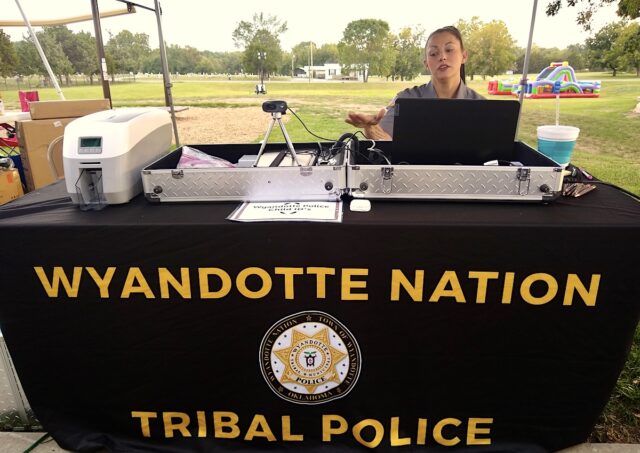

The Wyandotte Nation’s historic lands were in the area of Upper Sandusky, Ohio, about 70 miles north of Columbus. But federal removal policies relocated the tribe to Kansas and then Oklahoma, culminating in an east-west sliver of territory in the middle of what would become Ottawa County. The Wyandotte Nation has about 7,000 citizens, and its tribal police department also serves as the official police force for the town of Wyandotte.

While the March 7 decision is a win for advocates of tribal sovereignty, it also highlights significant disagreement about the direction of the state appellate court’s development of Indian law. Of the five judges on the OklahomaCourt of Criminal Appeals, all but Judge William Musseman wrote their own opinions.

Judge David Lewis’ three-paragraph concurring opinion was the most critical, accusing his colleagues of instigating “a counterrevolution in Indian law” based on their interpretation of the Castro-Huerta v. Oklahoma decision.

Lewis wrote:

I concur in the court’s conclusion that the Wyandotte Reservation was never disestablished by Congress. I continue to dissent from the court’s aggressive use of dicta in a footnote from Castro-Huerta as the charter for a counterrevolution in Indian law. Castro-Huerta’s application to this case is not even presented for our review. The last two pages of the (majority) opinion are thus dicta instructing lower courts in the future application of dicta.

Forced by the Supreme Court in McGirt to recognize the undiminished reservations of some of Oklahoma’s tribes, this court seems now to have set its sights on diminishing tribal sovereignty itself. The means for that project is “Bracker balancing” — the adjunct “jurisdictional analysis” by which state courts will weigh “tribal, state and federal interests” to decide whether prosecution of an Indian for a crime in Indian Country would infringe “tribal self-government.”

Rather than indulge the dangerous inference about the meaning of Castro-Huerta’s footnote that currently captivates this court, I will wait for stronger evidence that Congress or the Supreme Court has sanctioned this unprecedented state court intrusion upon tribal and federal sovereignty.

The footnote to which Lewis alludes from the majority opinion in Castro-Huerta hints that some Supreme Court justices could construe circumstances under which states had concurrent jurisdiction over Indians within Indian Country, something that does not currently exist in federal law.

“To the extent that a state lacks prosecutorial authority over crimes committed by Indians in Indian Country (a question not before us), that would not be a result of the General Crimes Act. Instead, it would be the result of a separate principle of federal law that, as discussed below, precludes state interference with tribal self-government,” U.S. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote, adding a citation to White Mountain Apache Tribe v. Bracker.

The Bracker balancing test originates from Thurgood Marshall’s opinion in that 1980 U.S. Supreme Court case. The test is applied to determine whether federal law has preempted state law regulating non-Indians on a reservation by examining the nature of the federal, state and tribal interests at stake and trying to balance each side’s interests.

Notably, the U.S. Supreme Court has never applied the Bracker test to an Indian in Indian Country.

Recent decisions highlight differences between judges

Lewis’ opinion was fiery enough for Rowland to address in his own opinion.

RELATED

With appeal possible, Deo decision says Oklahoma retains ‘subject matter jurisdiction’ in Indian Country by Tristan Loveless

“We see only this court, diligently striving to interpret and apply the decisions of the United States Supreme Court in an area of law that is in the midst of a sea change,” wrote Rowland. “(Lewis’) statements are an unfair attack on the court’s motives and are factually unsupported.”

The accusations and disagreement in the opinions from the Court of Criminal Appeals may signal the coming of a controversial opinion, or at least a decision with an outcome that is controversial among the judges.

Since at least December, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals has been heavily hinting at a desire to hear a case in which the “Bracker balancing test” could be applied to an Indian criminal defendant in Indian Country, a legal term of art applied to types of tribal land on which states lack authority to adjudicate criminal cases against tribal citizens and generally lack certain types of taxation and regulatory jurisdiction.

Any sort of state appellate court ruling that the state has concurrent jurisdiction over Native American criminal defendants who commit crimes within reservation boundaries would embark upon new legal precedent and would draw immediate appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

When the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals released the Deo v. Parish decision in December, every justice on the court wrote their own opinion, a highly unusual occurrence. That 3-2 decision held that Bracker balancing does not preempt state courts from exercising subject matter jurisdiction over a Native American defendant in Indian County, and it decision effectively flipped the burden of proof on defendants trying to have state charges dismissed based on Indian status in eastern Oklahoma.

After the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma, state prosecutors generally had to prove subject matter jurisdiction over Indian defendants for a case to proceed. Now, judges must allow cases to continue until defendants raise an objection based on personal and territorial jurisdiction.

While the state appellate court did not apply the Bracker test in the Deo case, the majority opinion noted in a footnote that “future cases” would decide the issue.

Bracker dispute spills over into Fuller opinions

The court’s disagreements over the Bracker test spilled over into the opinions in State v. Fuller, the case that affirmed the Wyandotte Reservation on March 7.

RELATED

The Wyandotte Nation’s long road to Land Back by Annemarie Cuccia

When arguing the Fuller case, the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office specifically did not brief the Bracker analysis and limited the appeal to the question of whether the Wyandotte Reservation continued to exist.

“At the oral argument held before this court on Dec. 14, 2023, counsel for the state clarified that for policy reasons, the state intentionally elected not to appeal the lower court’s ruling on the Bracker balancing test,” Rowland wrote. “Therefore, the only issue properly before this court is whether the district court abused its discretion in finding that the Wyandotte Reservation has not been disestablished and remains intact.”

In his opinions for both Deo and Fuller, Lewis raised his concerns about the future application of the Bracker balancing test. So far, the court has punted the application of the test to “future cases,” but eventually such a future case could come before the court.

A potential “future case” candidate before the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals that could draw application of the Bracker analysis is Stitt v. Tulsa, a traffic ticket jurisdictional dispute involving Gov. Kevin Stitt’s brother, Keith Stitt.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Facebook | X | Text or Email

Upcoming Stitt v. Tulsa appeal to have Bracker briefs

Keith Stitt, a Cherokee Nation citizen and the governor’s brother, is challenging a charge of aggravated speeding charge brought against him in Tulsa’s municipal court after he was issued a citation for driving too fast within the Muscogee Nation Reservation in Tulsa.

RELATED

A tale of two brothers: Kevin Stitt fights to limit McGirt ruling, Keith Stitt uses it to challenge ticket

by Tristan Loveless

As the case was pending before the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, the Five Tribes — Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, and Muscogee — all submitted amicus briefs in support of Keith Stitt, arguing the city’s municipal court did not have jurisdiction over an Indian defendant who committed a crime within Indian Country. Included in these briefs is an explanation of the tribal interests under the Bracker analysis.

On Feb. 7, attorneys for the United States requested to file a brief in Stitt v. Tulsa to present the United States’ “substantial interest in the allocation of criminal jurisdiction in Indian County” to the court. The motion marked the first time the federal government involved itself in the recent slew of Indian law decisions from the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals that began in December with the State v. Crosson and Deo v. Parish decisions.

On Feb. 23, the court granted the United States’ request to file a brief in the case, over an objection filed by the City of Tulsa. While the United States has not filed its brief yet, it is expected to include the federal interest of the Bracker analysis.

Since the City of Tulsa has briefed the state interest under the Bracker analysis, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals will be presented — for the first time — with briefings including all three required parts of the Bracker analysis.

A majority of judges on the court appear to have signaled their willingness to apply the Bracker test, with Lewis being a notable holdout likely to dissent to the test’s application:

- In both his Fuller concurring opinion and Deo dissent, Judge Robert Hudson wrote “we must apply the Bracker balancing test.”

- In his Deo concurring opinion, Judge Gary Lumpkin wrote that there is legal basis “for the application of the Bracker analysis, outlined in Castro-Huerta and set forth in this opinion, to determine if the state of Oklahoma’s action infringes on internal tribal affairs in cases where Congress has not specifically pre-empted the constitutional jurisdiction of the state of Oklahoma.”

- Musseman wrote the majority opinion in Deo v. Parish, holding the Bracker test did not preempt state subject matter jurisdiction over a tribal citizen who committed their crime within Indian Country.

- Rowland wrote in the State v. Fuller majority opinion that “the Supreme Court held that the General Crimes Act, by its very text, does not preempt state jurisdiction in any case and that any such preemption comes about as a result of the so-called Bracker balancing test.”

While those opinions appear to constitute a four-justice majority in favor of applying the Bracker balancing test to an Indian defendant charged for a crime committed in Indian Country for charges under the General Crimes Act, it is much less certain how the court may apply the test.

The Bracker test has been around for decades, and scholars note the wide variance in its application. Given that, predicting how the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals may or may not apply the Bracker test to an Indian defendant charged for a crime within a reservation would prove difficult.

Such a decision, if and whenever it comes, would likely be a first of its kind and could influence how other state courts interpret their criminal jurisdiction within Indian Country.