(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Warren Vieth of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

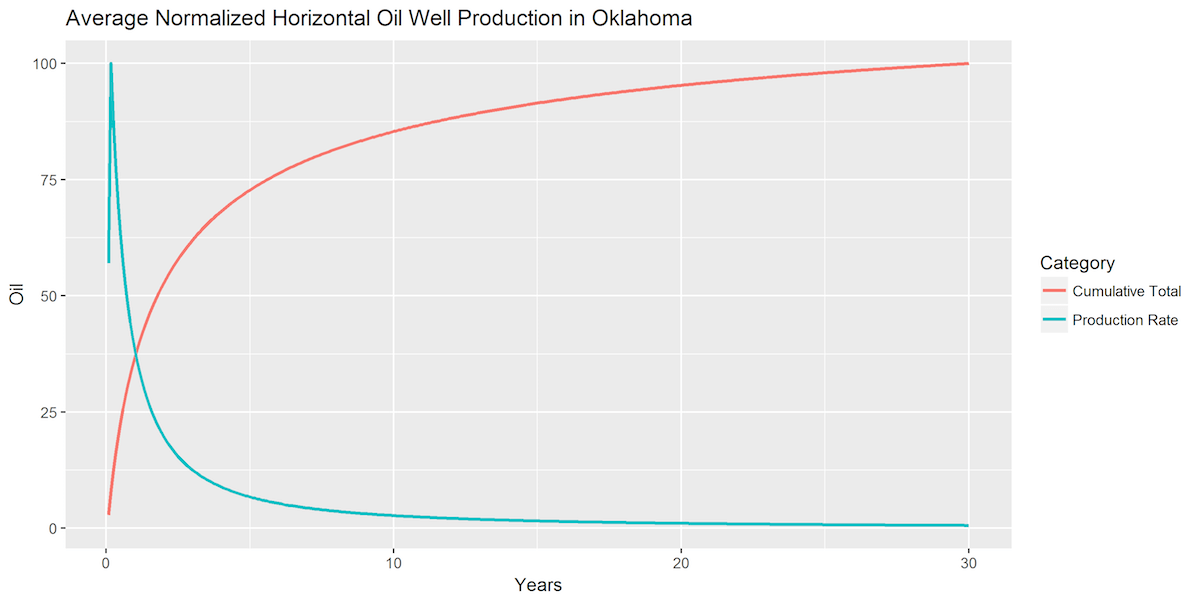

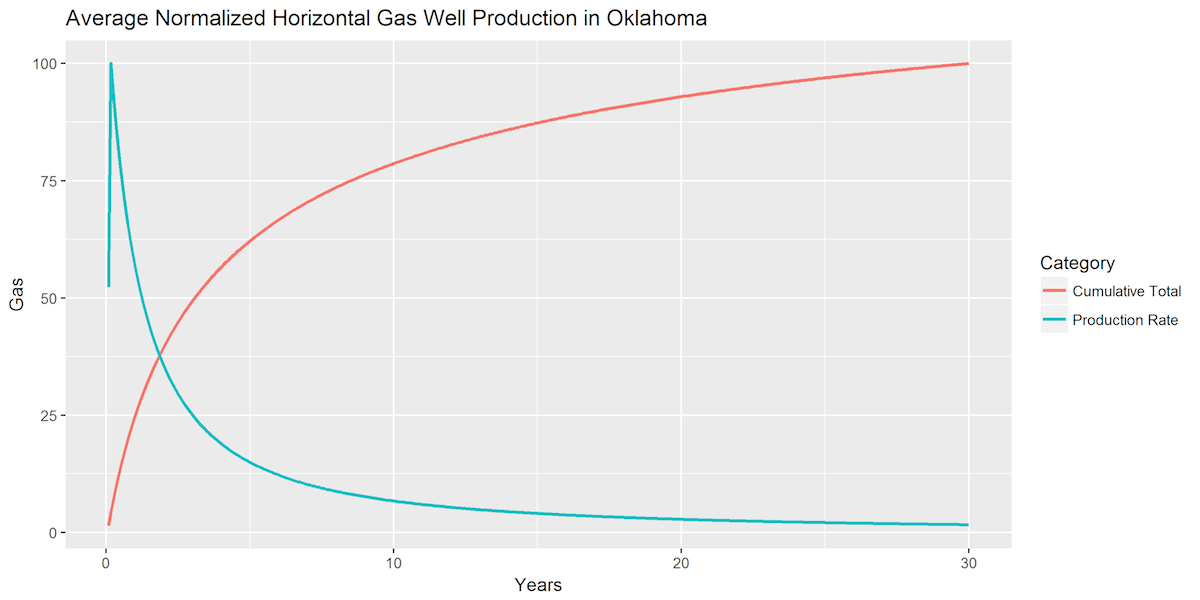

An Oklahoma Watch analysis of more than 3,000 horizontal wells shows that more than half of a typical well’s projected lifetime oil and gas production will occur during its first three years, when it is taxed at a much lower rate.

The analysis looks at all horizontal wells in the state that began production between February 2014 and January 2017. Oklahoma Watch obtained the data from the Oklahoma Tax Commission.

Wenzel Technology LLC, an Oklahoma City petroleum data analysis firm, plotted 30-year decline curves at Oklahoma Watch’s request to estimate how much of a typical well’s lifetime production occurs during any given month or year.

The findings are significant because they shed new light on how much money will be generated by the horizontal well drilling boom of recent years and how much tax revenue the state can expect to collect before the wells peter out over time.

“If you’re focused on policy in terms of taxation, it means you’re going to have to do it throughout the life of the well, or toward the front, if you’re going to get anything meaningful,” said Karl Wenzel, owner of the data analysis firm.

During recent legislative debates about the optimal level of taxation, lawmakers based their decisions on widely divergent estimates of how quickly horizontal well production is likely to decline.

One House member asserted that “most” of a typical well’s production would occur during the first two years. A petroleum engineer told legislators the halfway mark would not be reached until about four years.

The analysis by Oklahoma Watch and Wenzel Technology indicates the truth lies somewhere in between. Specifically:

- Following one year of sales, a horizontal well will have produced about 37 percent of its estimated lifetime oil production and 25 percent of its natural gas.

- After two years, the well will have produced about 53 percent of its recoverable crude oil and 39 percent of its gas.

- After three years, the point at which the state severance tax goes up, the well will have produced about 62 percent of its oil and 49 percent of its gas.

The Oklahoma Watch study shows that a typical horizontal well’s oil production starts out with a bang, averaging 267 barrels a day during the first full month of production. By the 36th month, its oil production will have fallen to about 34 barrels a day, a decline of 87 percent.

The Oklahoma Oil & Gas Association is preparing its own analysis of oil and gas production in the booming “Stack” oil play of northwest Oklahoma.

The industry study is not complete, but the association shared some of its data with Oklahoma Watch. It indicates that the biggest Stack operators are drilling wells with less steep decline curves than the statewide averages. The trade group’s initial findings are summarized in the accompanying story.

Rates rise after sharp decline in monthly yields

Under a tax structure enacted three years ago, all wells that began production after June 30, 2015, are taxed at a 2 percent rate for their first three years of production and 7 percent thereafter.

The Oklahoma Watch analysis suggests that formula will provide a blended average tax rate of about 3.9 percent for oil and 4.4 percent for gas over the lifetime of the wells.

In recent presentations to analysts, several oil companies have said their initial production rates are increasing as they develop improved well completion techniques. If that trend continues, a bigger portion of a well’s production would tend to occur during the first three years when the lower tax rate applies.

The steep decline curves help to explain why oil and gas companies have pushed hard in recent years to adopt a two-stage tax rate formula. The better they get at front-loading a new well’s lifetime production, the lower their tax burden will be.

House Majority Leader Mike Sanders, R-Kingfisher, said the Legislature might need to “reevaluate” the three-year, 2-percent formula if new data corroborates the sharp decline in production from horizontal wells.

“Most people, they’ve heard the numbers 2 percent, 7 percent. But I don’t think they realize that with a lot of these wells, most of the oil is taken out in that short an amount of time,” Sanders said.

“They’ll see that in three years. But by then, if you’ve planned incorrectly and banked on budget numbers thinking that it’s always going to be there, then you’re going to have a problem.”

From 1971 until 1994, Oklahoma’s tax rate was a uniform 7 percent on most production. In 1994, the state created a special incentive for what was then an exotic and expensive new technology. New horizontal wells would be taxed at only 1 percent for the first five years and 7 percent thereafter. That formula remained in effect until the three-year, 2-percent structure was approved in 2014.

Over the past five years, horizontal wells have become the norm. Fewer than 20 percent of all new wells are vertical wells, according to the Oklahoma Corporation Commission.

State Treasurer Ken Miller said he thought it no longer made sense to have a two-stage tax rate.

“I don’t know why you need it,” Miller said. “You’re pulling the oil and gas out of the ground the same way in the first 36 months as you are after that, and you’re doing it with a production process and technology that are the same.”

Miller acknowledged that when he was in the Legislature, he authored a bill to continue providing a lower tax rate during the first few years of horizontal well production.

“When the state began incentivizing horizontal drilling, the technology was new and expensive, and it was the exception,” Miller said. “Now it’s become the rule.”

Oklahoma ‘in dire need of revenue’

Pete Brown, a vertical well operator who co-owns Brown & Borelli Inc. in Kingfisher and Cimarron Production Co. in Oklahoma City, said he believes a single-rate system would be fairer.

“They put the incentive in place to attract people in to drill horizontally. Well, they’re here, they’re doing it, and the incentive doesn’t make that much difference,” Brown said.

Brown said he received royalties from horizontal wells and would have less income if the initial tax rate were raised. But he said he thought it would be the right thing to do.

“The state of Oklahoma is in dire need of revenue, which they lost a lot of due to the tax incentives that they gave the oil and gas industry, never thinking that almost all the wells would go to horizontal,” Brown said.

Two former state finance officials, Jerry Johnson and Michael Clingman, estimated in May that the amount of money available to the legislature for appropriation this year would have been $248 million to $313 million higher if all oil and gas production were taxed at 7 percent, beginning Sept. 1.

Oklahoma’s gross production tax rate is lower than the taxes imposed by most other states. A study conducted earlier this year for the state of Idaho calculated Oklahoma’s “effective” tax rate at 3.2 percent, the lowest of eight oil-producing states. The study included property taxes on oil and gas reserves in its calculation of effective rates. Oklahoma does not assess a property tax on oil and gas.

Neighboring Texas, for example, has an effective 8.3 percent rate when property taxes are taken into account, the study showed. Wyoming’s effective rate is 13.4 percent, the nation’s highest. The average for the nine states included in the study was 9.5 percent.

Donelle Harder, vice president of the Oklahoma Oil & Gas Association, said the trade group would continue to fight for a dual-rate structure because it helped ensure that current levels of drilling activity would continue.

A single-rate structure, Harder said, would “put at risk is how much of a presence we will have” in Oklahoma.

Rig count statistics show that some states with higher tax rates, including North Dakota and Utah, experienced much sharper declines in drilling activity than Oklahoma did after oil prices plunged in late 2014.

“In the current commodity price environment, this two-tier gross production tax is allowing companies to more quickly be able to drill new wells in Oklahoma,” Harder said.

Wenzel, who did not take sides in the taxation debate, said he thought tax writers needed to strike a delicate balance.

“I would say there are two sides to this story that policymakers need to concern themselves with,” Wenzel said. “One is that investors are worried about getting a return on investment. The other is that if you’re going to get any serious revenue off these wells, if you wait too long, it’s gone.”

For more information on the analysis, go to this link.