NORMAN — Before beginning her training at the police academy in September 2016, Norman native Jennifer Bryan taught aerobics at the YMCA for nine years.

Now 37 and a single mom of four, she’s one of Norman’s newest police officers during a time of nationwide mistrust between officers and the communities they are sworn to serve and protect. The shootings of unarmed black men have taken center stage — including shootings in Oklahoma — and, on July 15, an Australian woman was shot and killed by a Minneapolis Police Department officer. The event caused international outrage.

Conversations are happening across the country about how officers could be trained to use less-than-lethal means of force to de-escalate tense — and potentially fatal — situations. But there isn’t a panacea to the excessive-use-of-force issues cities across the nation are experiencing. Rather, experts say, it’s a multi-faceted approach that might include better training tactics, a focus on making the demographics of police departments look more like the cities they police, and lifting the burden of resolving social issues off the shoulders of police officers.

‘Diversity is key’

Norman Police Department public safety information officer Sarah Jensen said recruiting officers of varied backgrounds is important to the department.

“Diversity is key to this department and has been a goal of the chief’s since he’s come into his role here for the last six years,” Jensen said. “So I would think we’re a progressive recruiting department.

“We would never want to lower our standards to meet certain areas. That’s never been the goal, but diversity is key.”

According to data provided by the department, NPD’s most recent academy graduated 15 officers to serve in the city’s police force — two officers were female, including Bryan, putting the total representation of women at 13.3 percent of academy graduates. This proportion of females roughly matches (within 2 percent) the current status quo of female officers in law enforcement agencies on the national level, which is 11.6 percent of all officers, according to the FBI’s most recent available data. (Females made up only 8 percent of all officers in Oklahoma that year, according to the same data set.)

But the officers who graduated from the 54th NPD academy, Bryan’s class, were not racially diverse. Whites comprised 86.7 percent of the class who graduated and moved on to NPD’s next phase of training, with only two officers (13.3 percent) identifying as Asian/Pacific Islander (both of those officers are male.) No officers of other races represented the department at graduation.

Data show NPD lacks diversity in specific areas

While Norman Police chief Keith Humphrey is black, he represents the only racial-minority officer in the entirety of the first-line supervisor, mid-level supervisor and executive-level ranks in the department. Racial minorities do comprise 12.4 percent of total line-level sworn officers — 21 out of a total of 169 sworn officers. The most recent city demographic data available on NPD’s open data portal indicate whites make up 81.1 percent of the total Norman population, while 18.9 percent represent non-white races.

Meanwhile, although women make up about half of Norman’s population, females constituted only 7.1 percent of all sworn officers in the department. There were no women of color represented in the ranks of sworn officers. Further, any time NPD made a contact with a member of the public during 2016 and the gender of the person was reported, 41.7 percent of the time the person contacted was female, according to open data provided by NPD.

As such, the department is doing better representing racial minorities than representing women when compared with the general Norman population. The department’s 12.4 percent of minority officers is much closer to the city’s actual demographics than the numbers for women.

These disparities may have to do with the difficulty of recruiting diverse officers in police departments in general.

“I think that recruiting is challenging in the police industry as a whole right now, mostly just because of the view of police in the media spotlight that has made it difficult for recruiting in some instances,” Jensen said. “At the same time, people will tell you that if you have a drive to serve your community, that doesn’t have an impact.”

‘Struggle on both sides’

Shay White is a black community leader in Tulsa who said she has personally experienced racial profiling from law enforcement. She said the relationship between police and citizens is fraught with “some disdain.”

“I think it’s a struggle on both sides as how to work better with each other due to the tension from the multiple police brutality and shooting incidents,” said White, who is running for Oklahoma House District 77 in 2018. “People closest to the problems usually know how to solve the problems, and if (more) people of color were on the police force, then maybe they could be advocates.”

White says having people of color on police forces is necessary, but she noted that assessing each officer-citizen situation on an individual basis should take priority.

“There can be an incident with a police [officer] of color that uses brutal force against another person of color or anyone, so I think dealing with the way they see situations and respond to them — no matter what color they are — is more important than diversifying the police force,” she said. “Adding a few people of color to that [law enforcement] system won’t reinvent the culture or replace the culture. I think, overall, there needs to be some kind of shift in the way police interact with civilians.”

In pockets of America, necessary conversations are happening

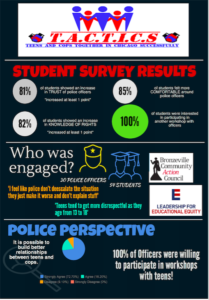

Tenth graders in south-side Chicago’s Wendell Phillips Academy High School created a program of workshops where officers from their district came to the school and interacted face-to-face with students.

The program consisted of workshops meant to enhance students’ understanding of their rights when contacted by police. Those workshops also sought to allow the officers access to teens in a calm, neutral setting to talk about fears and what appropriate responses might look like — from both sides.

According to teachers Corinne Durrette and Gabrielle Benoit, the officers who participated in the program said that they enjoyed having a space to interact with students that wasn’t reactive or negative. Further, 100 percent of students surveyed after the workshops indicated that they would like to participate in another workshop with officers in the future.

Students dubbed the workshop series T.A.C.T.I.C.S., which stands for Teens and Cops Together in Chicago Successfully. A partnership between The Aspen Institute and the Bezos Family Foundation facilitated the student-designed program.

“As teachers, so much of we’ve been taught [emphasizes] the importance of having ‘culturally responsive practices,’” Benoit said in a phone interview. “So if you cannot get the diversity of demographics that you’re looking for, you do need to be responsive in your practices to ensure that you are serving your population in the best way and the most effective way.”

University of Oklahoma adjunct instructor of African and African-American studies Ebony Iman Dallas has attended public forums between police and African-Americans that opened up the possibility for conversation and mutual understanding.

“[They can] talk about their cousin that keeps getting pulled over for no reason or their cousin that lost their lives to the police brutality,” Dallas said via WhatsApp voice call from Somaliland, where she is currently traveling and working. “I think having those types of conversations, of course, it’s not gonna be comfortable, particularly for the police department to have to hear those things, but I think it’s really important to start to have those conversations to build trust. And then everybody gets their side heard, and we start coming to some understanding of each other’s perspectives.”

‘A start in the right direction’

Some of the conversations that African-American studies teacher Dallas champions are already happening in Oklahoma, said OU vice-president for the university community Jabar Shumate.

Shumate offered a glowing review of NPD chief Humphrey and said the chief works closely with his office to resolve issues regarding minority communities when they arise.

“Partnerships really first start with relationships and relationship-building, meaning that there’s a greater understanding of not only our students, [but also] our faculty and staff, in which we know each other not in a situation of conflict or adversarial behavior, but there are times where we can build true relationships first where there’s trust,” Shumate said. “[The police-university relationship] is not where we want it to be, but we continue to work on it, and most important is we have the relationships, I think, to be effective at building (…) a better relationship with the police department. We continue to work at it, and one thing I can say about Chief Humphrey and the Norman P.D. is they are very, very intentional on their work with us to build better relationships.”

Humphrey concurred with Shumate, saying that having open dialogue is vital to maintaining positive police-community relationships. According to Humphrey, NPD has been able to avoid the excessive use-of-force incidents seen in other parts of the nation, in part, because of these conversations.

In an email interview, Humphrey said avoiding such incidents has been “a team effort that starts with both the chief and citizens of the respective city establishing the tone for the expectations of the department’s officers. Ensuring that all officers have the mindset of a guardian and not only of a warrior.”

He added that policy and training must be reviewed continuously to reduce use-of-force events.

When it comes to officer diversity, however, Humphrey acknowledged there is work to be done.

“When the topic of diversity is mentioned, some become nervous,” he said. “It is not solely about race or ethnicity. Diversity is recognizing differences and working to understand and embrace those differences.

“I do strongly believe that every organization should resemble the communities it represents. Getting ahead of the concern and admitting there is a need for improvement is a start in the right direction.”

‘Change the mission of the police’

In a Newsweek article from May 2015, Delores Jones-Brown — John Jay College of Criminal Justice professor and founder of the school’s Center on Race, Crime and Justice — said more diverse departments don’t necessarily or causally lead to fewer incidents of excessive use of force, but that it’s “a combination of diversity and better training [that] should lead to better results.”

But not all academics agree that changes from within the police department — such as de-escalation training or diversity workshops — will be effective in reducing violence or inherent racial biases in departments. Brooklyn College professor of sociology Alex Vitale said changes need to come from the outside — from elected officials who define the mission of police departments.

“Ultimately, [internal police reforms] will produce at-best incremental changes, marginal improvement,” Vitale said via phone interview. “We have to get to the root of the problem, which is that we’re asking them to do stuff they shouldn’t be doing.”

Vitale suggested changing the mission of policing.

“Get rid of the war on drugs. Quit trying to solve all the social problems by arresting people, whether they’re mentally ill, whether they’re homeless, whether they’re young people acting out in schools,” he said. “These are not police problems. These are problems which should be solved in other ways.”

By other ways, Vitale is referring to social programs that focus on specific problems most communities presently face.

“[The programs are] all external to policing. We don’t need police homeless outreach units; we don’t need police mental health-crisis teams. We need actual social workers who have access to housing and other social services to do outreach to homeless people,” he said. “And we need trained mental health workers to do outreach to people with mental illness.

“So what I’m saying is we need to pressure elected officials to start putting those alternatives in place and redirecting money from police, courts and prisons into those alternatives.”