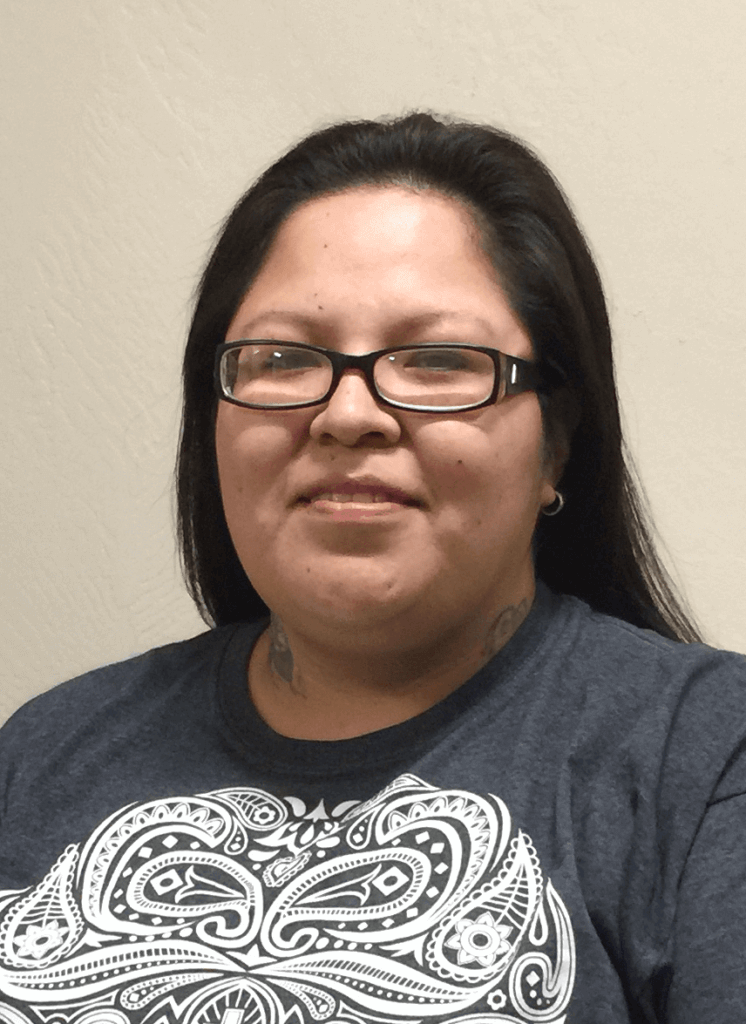

SHAWNEE, Oklahoma — Fawna Wolfe leans into her husband, Daniel, as people speak. The two are gathered, along with about eight others, at a meeting in a nondescript building off a road in Pottawatomie County.

The duo listens as peers recount their path to sobriety and how they stay clean in a world teeming with vices.

Wolfe, 36, looks forward to the Wednesday night meetings put on by the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, part of a Tribal-Reentry Program to help Native Americans in the Shawnee area live productively following incarceration.

“Prison is not for me,” Wolfe said during an interview before a Jan. 10 meeting.

The mother of five spent 16 months in prison following a 2010 DUI with personal injury in Seminole County.

“I was drinking. I had smoked meth, and my passenger, whenever we wrecked, he had hit the dashboard and split his lip,” she said.

Initially placed in drug court, Wolfe said she lacked a stable place to live for several years and continued to abuse substances while in drug court.

She left the program without permission, and, in 2014, while driving in Oklahoma City, she was pulled over, arrested and sent to prison. She rotated among women’s prisons in Oklahoma and learned that idle time is the enemy, she said. So, she enrolled in a Career Tech program while at Eddie Warrior Correctional Center.

“Mabel Bassett [Correctional Center] was the worst, seeing the girls. Seeing the lifers,” Wolfe recalled. “I kind of learned and know that’s not a place for me.”

A member of the Seminole Nation, Wolfe said she found little support from her tribe while in prison. She turned to the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, which accepts American Indians from a variety of tribes, for its reintegration program.

‘I’m a proud Indian, and I want to make it on my own’

CPN’s program started about five years ago thanks to a Department of Justice grant. It provides money to help buy work clothes and pay utilities for recently incarcerated individuals who are members of local tribes. If attendees show they have kept a job for a specified time frame, the program helps them rent an apartment or find other housing. They also provide substance abuse treatment at clinics in Oklahoma City if that’s needed, as well as GED classes, vocational-tech and college classes, and help with transportation.

“We go in there in the prison system and try to get the guys getting out in three months, get them qualified if they’re going to be in our service area,” said Burt Patadal, coordinator for the CPN’s Tribal-Reentry Program. Several other tribes in Oklahoma have similar re-entry programs, but many are only for citizens of that tribe.

Patadal believes one of the most beneficial parts of the program is the talking circle, where participants discuss issues relating to their current and former lives. This could include talking about drinking and using drugs, but it can also touch upon the participants’ cultures and families. A key lesson is self-sufficiency.

“They need to get self-sufficient,” Patadal said. “We try to get them to feel like, ‘I am somebody. I’m a proud Indian, and I want to make it on my own, and I don’t want to let someone else do it for me.’”

‘They have to want to quit’

Mary Lou Peacore, 58, is another program participant who turned her life around. Locked up twice since 1999 for DUIs, the grandmother of eight has been clean and sober for three years.

On Wednesday evenings, Peacore can be found in the program’s kitchen, cooking foods like cornbread, fried potatoes, nacho chili and beans.

“You can’t force nobody,” said Peacore. “They have to want to quit.”

In the past five years, about 300 people have completed the Citizen Potawatomi Nation’s Tribal-Reentry Program. Only one person has returned to prison, Patadal said.

During a recent meeting, the 69-year-old Patadal — who himself dealt with alcoholism for decades before becoming sober 26 years ago — spoke about getting a job no matter what the cost.

“If you need a job, there’s always McDonald’s,” he said, adding that he once worked at two different McDonald’s — one in the morning and one at night.

Patadal also read out of the White Bison book, which Wolfe said brings back memories of growing up in a traditional Indian church and being raised by her grandmother, who spoke fluent Seminole.

“Burt says words in Seminole. He says bits and pieces in Seminole. We answer him back,” she said. “I know words, bits and pieces.”

‘It keeps me sober’

Such lessons have caught Wolfe’s attention and brought her back week after week. So far it has worked out for her, and she has decided against returning to Seminole.

“I grew up there. I just didn’t want to go back,” she said. “You know everybody, and if I was to look for drugs, I know exactly where to go.”

Since arriving in the Shawnee area and joining the reintegration program, Wolfe has landed a job at a manufacturing facility. The CPN’s reintegration program helped her buy work boots for the job, an electric bike to get to work and a deposit for a house.

“It’s important because it gives me something to do, and it keeps me sober,” she said.