The leaders of criminal justice reform efforts in Oklahoma say the state needs change for two reasons: Outrageous system costs are busting the state budget, and mass incarceration harms public safety and security.

But several Oklahoma district attorneys and their allies say conflating those two notions is a mistake. They fear advocates are pushing too many reforms too quickly without considering unintended consequences.

The result of these competing perceptions? A stalemate in the 2017 Oklahoma legislative session on a handful of bills intended to reduce prison populations, shorten criminal sentences and reform the classifications of certain crimes.

“Look, this issue of mass incarceration is impacting our state in a very negative way,” said Kris Steele, a former Speaker of the House who has spearheaded Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform in recent years. “We are beyond the point of having to reconsider our policies, and ultimately the Legislature has to determine to base their decisions on the data, on the facts and on the research. Not on fear, not on emotion and not on anecdotes.”

Steele says data and research provide clear evidence that the measures he, Gov. Mary Fallin and a mix of liberal and conservative action groups tried to pass this year are needed.

“It was a very diverse, deep coalition,” said Steele, who also serves as the executive director of The Education and Employment Ministry. “The support continues to grow, and for legislators to ignore that and not allow the issue to be discussed and voted on is concerning. This is real life stuff. This is families and individuals who are ultimately being swallowed up.”

‘There are lives on the line’

Despite Steele and Fallin’s efforts, several of the bills pushed for this year were held up at the end of session by Rep. Scott Biggs (R-Chickasha), chairman of the House Judiciary Committee on Criminal Justice and Corrections. A former prosecutor, Biggs had identified a major problem with some of the bills that modified laws in Title 57 of Oklahoma statutes.

Criminal Justice Reform bills

2017 Oklahoma Legislature

(Summaries from OK4CJR)HB 2284, which would require public defenders to receive continuing education training regarding best treatment practices for defendants with substance abuse or mental health problems and would require training for judges and state prosecutors on how to best deal with victims of domestic violence and trauma. The training is contingent on funding availability. (SIGNED)

SB 603, which would improve the risk assessment process and require the development of individualized plans for inmates to help them better reintegrate into society. (SIGNED)

SB 604, which would provide training for law enforcement officers on how to better deal with victims of domestic violence. (SIGNED)

HB 2286, which would modify the training and qualifications of the Pardon and Parole Board as well as enhancing transparency for the general parole process. It also would require the use of evidence-based community supervision with standards created by the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services.

HB 2281, which would create graduated penalties for certain crimes.

HB 2290, which would expand the parameters of drug court program objectives, would allow the introduction of alternative treatment plan in lieu of revocation and would provide sentencing options for certain offenders who successfully complete a drug court or mental health court program.

SB 609, which would establish the framework for a training and certification process for professional victim advocates.

SB 649, which would distinguish between those who have a history of committing violent crimes from persons with a history of committing nonviolent offenses in determining how much their sentences should be enhanced for being repeat offenders

SB 650, which would reform qualifications for certain expungement categories.

SB 689, which would allow judges and prosecutors more options in diverting people from prison to treatment and supervision programs. It also would decrease financial barriers for convicted individuals seeking to re-enter society, would expand the use of graduated sanctions and incentives that could be used in response to inmate behavior and would expand eligibility for certain programs that are alternatives to incarceration.

SB 786, which would create an additional burglary tier to distinguish by severity.

SB 793, which would set up an oversight council to monitor the effectiveness of criminal justice reform efforts.

“Title 57 deals with prison reformatories and what qualifies as violent or non-violent when you’re talking about earned credits or when you’re talking about parole. Title 21 deals with what is truly a violent crime compared to everything else,” Biggs said in an interview toward the end of session. “They’re just saying if they’re not 85 percent (crimes), then they’re non-violent, and that’s simply not true. Domestic abuse by strangulation? I’m pretty sure there’s a victim who would consider that a violent attack. Hate crimes? Ask a person around in the public walking the street, ‘Do you think hate crime is a violent crime?’ The answer is going to be, ‘Yes.'”

Some of Biggs’ concerns were addressed in amended versions of the bills, but the former district attorney still declined to hear the measures in committee despite pleas from Fallin and others.

“There are lives on the line and future generations of children that will be affected if we don’t pass smart-on-crime criminal justice policies in our state,” Fallin said during a press conference aimed at pressuring Biggs. “The public supports, in a bipartisan way, all walks of life, criminal justice reform in our state.”

‘A big leap of logic’

Count Washington and Nowata County District Attorney Kevin Buchanan as someone who finds that messaging disingenuous.

“I think we’re moving too fast. I totally understand the reason behind this, but I think the number one reason behind this, simply put, is money,” Buchanan said. “When we see the statements coming out of the Legislature and the governor’s office saying, ‘In order to strengthen public safety, we want to do the following things.’ Well, none of this is strengthening public safety. It’s just not. What we’re doing is saying we don’t have enough money to continue doing what we’ve been doing.”

Buchanan, who spent the first 26 years of his legal career in private criminal defense practice, criticized this year’s stalled bills as coming too quickly on the heels of SQ 780 and SQ 781, which he said pose their own unintended problems.

“State Question 780 said, ‘We want to change all drug (possession violations) to misdemeanors, and we want to raise the (felony) threshold of all theft crimes to $1,000,'” Buchanan said. “For some reason, the Legislature and the governor took that to mean the voters wanted to begin changing things like probation, what cases are violent crimes or not violent crimes. (That) is a big leap of logic without a bridge to cross on it.”

Like Biggs, Buchanan fears further unintended consequences like the ones he has seen from SQ 780.

“Here’s what part of the complicating factor is. It’s not so much the funding for drug court,” Buchanan said. “I’m going to say that anywhere from a third to 50 percent of the people in my drug court program — and every Monday, I’m in drug court — are there because of drug-possession-related offenses. So now, July 1, when all those offenses become misdemeanors, those people are no longer eligible for drug court.”

He said drug court often forces spiraling and escalating addicts to take treatment more seriously.

“Drug court is a great tool,” he said. “But 780 took from me the ability to put people in the program. Misdemeanors don’t qualify.”

Buchanan said drug courts — which are not available statewide — deal with many offenders who commit theft crimes. But that will also change under SQ 780’s higher threshold for theft felonies.

“780 took away the eligibility of the vast majority of people that now are populating my drug court,” he said. “Really all it left are felony DUIs, and unless people are stealing more than $1,000 worth of things, I can’t get them in on theft charges either.”

He said since most guns are not worth $1,000, stealing firearms will become a misdemeanor. Meanwhile, he is concerned that the new treatment programs intended to arise from state savings based off SQ 780 will not receive funding for at least another calendar year.

“Our plan is supposed to be to start directing these people to the treatment options that 780 and 781 are counting on as key to 780 and 781 working. But those treatment options don’t exist,” Buchanan said. “They’re not there now, and they’re not going to be there July 1. So for the coming year, we don’t have any options.”

‘Over-stuffed and under-staffed prison system’

“It goes back to trying to do everything in such a big hurry that we’re sort of performing actions and then, by surprise, finding out what the consequences are,” Buchanan said. “They addressed some of those issues (in the 2017 bills), but the problem is the list that was provided by our organization to the Legislature to point out, ‘Hey do you realize this is what you’re doing?’ that was not an exhaustive list. We just pulled up some that were on the violent crime list. Our desire is that we slow down a little bit and make sure we study this.”

Biggs will be doing just that in a yet-to-be-scheduled interim study on the topic of violent and non-violent crime designations. To that end, everyone involved agrees criminal justice reform will be back on the table for the 2018 legislative session, but specific language is currently uncertain.

“What I’m hoping happens and what I’m going to do my best to be a part of is to bring all sides together and see if we can reach agreement on the language that should be in those bills so we can run them out next year quickly, just like we did REAL ID this year,” said House Majority Floor Leader Jon Echols (R-OKC).

Echols said he would have voted yes on the bills had they reached the House floor this year, but he defended his decision not to move the bills out of Biggs’ committee to get them there.

“Was leadership capable of moving those bills? I mean, of course. But I’ve had a solid track record this year that I’ve not moved bills unless both chairmen agreed,” Echols said. “Now, next year, do I have to assign those bills to Rep. Biggs’ committee? That’s a different issue.”

House Minority Leader Scott Inman (D-Del City) said he appreciates Echols’ commitment to hearing the bills in 2018, but he wished Echols and House Speaker Charles McCall (R-Atoka) would have taken action this year.

“It has been a passion for me and my caucus over the past five years to truly get smarter on how we handle the criminal justice system,” Inman said. “I appreciate Leader Echols’ desire to do the right thing on criminal justice reform next session, but the problem is we had the chance to do something on it this session.”

Inman said Oklahoma’s mass-incarceration practices functionally create “wards of the state” that are unable to find jobs after years of incarceration for felonies.

“Criminal justice reform has far-reaching impacts on the state,” he said. “Not just on the state’s budget or the over-stuffed and under-staffed prison system, but also on the lives of those people incarcerated and the lives of their families left behind.”

‘Get the damn bills to the floor’

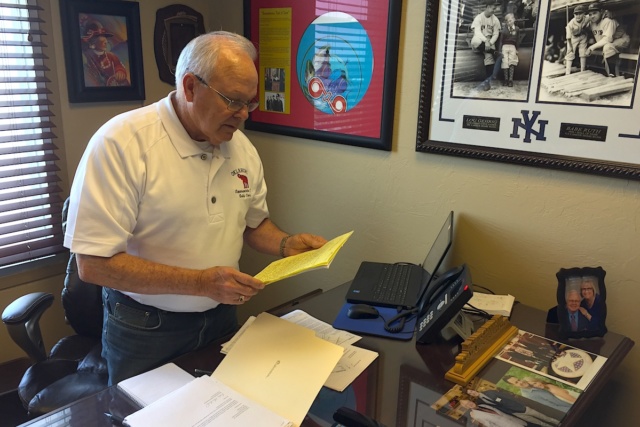

Rep. Bobby Cleveland (R-Slaughterville) has been visiting Oklahoma prisons since he was first elected in 2013. He regularly receives letters from inmates he met or who had heard of his visits.

He called the stalling of the bills “inexcusable.”

“In 1907, Kate Barnard was talking about what we’re doing today,” Cleveland said. “‘Stop warehousing. Stop putting people in prison. Try to help them.’ We’re making them meaner in prison, and we need to be teaching them.”

Rep. Cory Williams (D-Stillwater) criticized Biggs for blocking votes on the proposals.

“I happen to believe that you can honor victims and also provide value to the state of Oklahoma with the punishments you’re handing out and do it better to prevent victims in the future by changing the damn cycle,” Williams said. “The problem I have is this lack of transparency, this mockery of the process. Get the damn bills to the floor.”