(Correction: This piece was updated at 3:55 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 22, to note that the attorney actions referenced in the civil case below were made on behalf of the Texas church and not the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma. NonDoc regrets the error.)

In a legal analysis recently published by NonDoc, the question was raised, “How does a 36-year-old man avoid jail time after admitting to the rape of a 13-year-old girl at an Oklahoma church camp?”

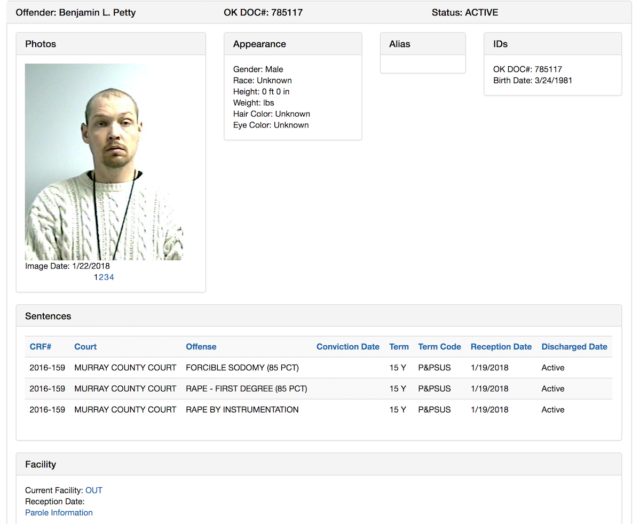

Instead of a criminal trial, the plea agreement that was made with the perpetrator given no prison time for first-degree rape, forcible sodomy and rape by instrumentation.

The analysis describes the legal pitfalls that could further harm the victim if a criminal trial were to have proceeded:

- She could have been forced to re-live the rape by giving testimony during a criminal trial.

- Her former sexual activity could have been called into question.

- Her past words and behavior could have raised doubts about her claims.

- The rapist could have been acquitted and would face no punishment at all.

- A possible acquittal could have jeopardized a future civil lawsuit and restitution for the victim.

Quotes from the legal professionals involved in the case cited reasons for why the deal was struck and how compromises were made solely to benefit the victim.

But was she truly spared further harm? Who stands to lose or gain the most by allowing her rapist to go free? How will any future victims be spared if he attacks again? And what will prevent more assaults at the religious camp?

While all of these questions remain unanswered, they lead to the most pertinent, far-reaching questions of all: What is the impact of failing to hold sex offenders fully accountable for their crimes, and how does this lack of accountability perpetuate a culture of shaming survivors into silence?

Statutory rape charge would have been better

Something very important is buried within the legal discussion of how the victim could have been subjected to further harm during a criminal trial, and that is how she should have been protected so that her attacker could be rightfully prosecuted and put behind bars. Only one fact truly matters, and it is indisputable: 36-year-old Benjamin Lawrence Petty raped a 13-year-old girl. Anything that could have been used in a cross examination to discount that fact should have been irrelevant because children are not capable of consenting to sexual activity of any kind.

Even if Murray County Assistant District Attorney David Pyle (since resigned) had doubts about securing a conviction on the first-degree rape charges, the least he could have done was charge Petty for statutory rape and push for maximum sentencing, which would have included jail time. And even if Petty’s defense attorney would have made an attempt to discount the victim’s claim, Oklahoma law only makes one exemption to statutory rape: when a minor over age 14 consents to a partner under 18, which this case clearly fails to meet.

Oklahoma’s Rape Shield Statute should have protected the victim from anything else brought into question. The victim, possibly, would have avoided taking the stand at all, especially if DNA evidence of the rape was provided.

District 20 judge now under fire

District 20 Judge Wallace Coppedge, who presided over the criminal case, could have rejected the deal and ordered Pyle and Petty’s defense attorney, Lee Berlin, to come up with a more acceptable negotiation that included prison time. Or, the judge could have forced Petty to face a trial that could have resulted in a maximum prison sentence.

Court transcripts (embedded below) show that the judge asked the family’s civil attorney, Bruce Robertson, if the family was in agreement with the plea deal. Robertson answered affirmatively but attempted to elaborate before being cut off by the judge, who said, “They either are or are not.”

As of Feb. 18, a petition calling for Coppedge’s removal from the bench had garnered more than 87,000 signatures from people around the country who are outraged that he allowed such a lenient sentence.

So, was it the judge’s responsibility to overrule what he perceived to be the family’s wishes in the name of justice?

Questioning the motives behind the plea deal

Robertson released a statement that said the family only agreed to the deal because Pyle led them to believe there was no other alternative and that Petty would not serve meaningful prison time because of medical conditions. He said Pyle’s final recommendation came after he had already assured the family his office would never agree to a plea that did not result in significant incarceration. But Pyle said the family never asked about an alternative deal. Who is telling the truth? Is there another motive behind the family’s agreement for the plea deal?

Defense attorney Berlin asserted that Robertson and the family clearly knew the details of the deal and willingly accepted it because they only cared about securing a guilty plea for the civil case, which could produce a payout. He even encouraged Pyle to test his theory by presenting the deal to Robertson and the family. If they easily agreed, there was Pyle’s answer. Their agreement then gave Berlin the leverage he needed to secure such a light sentence for his client.

Civil case underway

But Petty’s plea-deal confession was supposedly needed to clear a path for the civil case recently filed on behalf of “Jane Doe”, the name used to protect the minor’s identity.

The Baptist General Convention, owner and operator of the camp, along with two other churches that arranged Jane’s attendance and allowed Petty to volunteer as youth sponsor, are all named as defendants. The Texas chuch’s attorney is already digging into the girl’s past — including prior sexual abuse or activity that took place — to prepare for a defense strategy that should have been prevented in a criminal trial. In this case, however, she may not be afforded such protections, because shield laws are not applicable to civil lawsuits in Oklahoma.

Though she may never have to enter the courtroom (since many civil cases settle before going to trial), Jane will certainly be forced to re-live her rape during this lawsuit. Without shield-law protections, she could possibly be asked to recount even more trauma that took place outside of the rape. She could still be subjected to aggressive and coercive questioning, in this case by a high-profile forensic psychologist already hired by the Texas church poised to minimize monetary damages and salvage the reputation of Falls Creek Church Camp. Yet, her rapist walks free.

Final questions, boiled down

Though serving no time for his crime, Petty will serve 15 years of probation, be forced to wear an ankle monitor and forever be required to register as a sex offender. He risks the possibility of vigilante justice and public shaming by former social circles and may also face challenges to support himself financially because of his new criminal record. So why would his lawyer advise him to accept a plea deal when there was so much talk about a high risk for acquittal? After all, attorneys (and district attorneys) must discuss the details of their cases with each other in order to negotiate such deals in the first place. If Petty did accept the deal to avoid prison, why was such an option made available?

This all begs some final critical questions: How many people does it take to fail a 13-year-old rape victim? Was the plea deal really agreed upon by all parties as the best way to spare her from further damage in a criminal trial where her age clearly ruled out consent, and one in which shield laws should have protected her? Or, was there time to be saved by a judge, money to be made by a civil attorney and the girl’s family, a conviction rate to be maintained by a district attorney’s office, and prison time to be avoided by a defense attorney for his client?

In the legal world, it all comes down to strategy and basic risk/benefit analysis. In the bigger picture of society, however, leniency for sexual assault criminals inflicts the biggest damage of all by sending the messages: 1) to assailants that they won’t be held fully accountable for their crimes, and 2) to survivors that assaults aren’t to be taken seriously — they will be doubted, discounted and ultimately silenced.

Loading...

Loading...