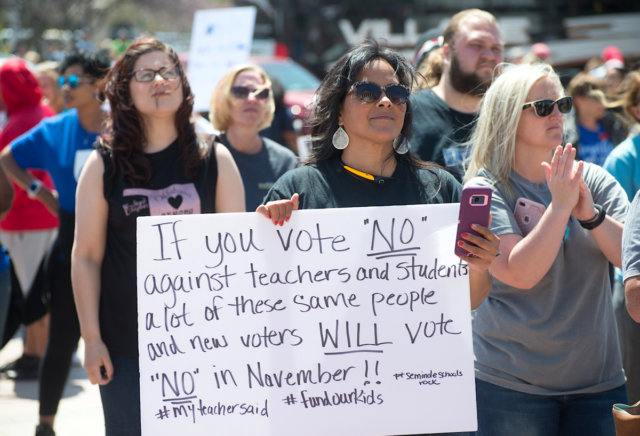

On a recent day of the Oklahoma teacher walkout, educators could be overheard asking, “Where is Floor Leader Echols’ office?” “Oh come with me, I went there yesterday, it’s this way.” The civic engagement transformation over the last two weeks has been exhilarating.

Students and teachers have seen what House and Senate sessions look like, heard how information circulates through the building, and learned a lot about the little interpersonal mechanics that keep state government running.

Some teachers have expressed a wish: that they would have been prepared with more civics education when they were students. Over the past two weeks, many students have begun to shift from amorphous concepts of political action to strategic concrete tactics.

Students know their voices will be powerful in shifting the needle toward fully funded public education in Oklahoma. But they don’t always know exactly how to leverage that power.

Public education requirements in Oklahoma include very little in the way of civics. High school seniors take a government class which is, in practice, a glorified recap of fifth- and eighth-grade history. They learn about the three branches of government, federalism and financial literacy. State standards include goals for students’ civic knowledge, but no curricular framework ensures civic participation as a priority.

Knowledge of what is going on is necessary

Government class may touch on the importance of voting, but it remains viewed as an essentially easy, if tedious, course.

Students who find politics inherently interesting may seek out information online, but the civic knowledge that can lead to passionate engagement is not systematically offered to all Oklahoma students. And prior political awareness has been a key indicator of which students would directly engage in the walkout.

Engaging students in action-oriented civics education could have prevented the decade-long trend of electing incumbents who have proven through their voting record that they do not prioritize education spending. Candidates typically target those 45 and older, as they vote in the highest numbers. This age group is not as directly affected by legislation that impacts public education; it is no surprise that Oklahoma’s elected officials reflect the priorities of this voting block. If 18-24-year-olds had been consistently voting over the past 10 years, perhaps the state of education funding would not have spiraled so drastically.

In the context of a mass protest at the Capitol, knowledge of what is going on is necessary to the perpetuation of the movement toward the specific goal. But the scale is also a draw; a mass protest is the perfect venue to hook people onto civic involvement and give them the tools to remain connected in meaningful ways in the future.

Teachers and students learned how state government functions on the fly in the two weeks of this walkout. Kids have grasped the difference between things like their state legislators and federal representatives — a bittersweet sight. It has been bitter because their civic education has failed them so dramatically, but it has been sweet because it serves as proof of the education that can come from being directly involved.