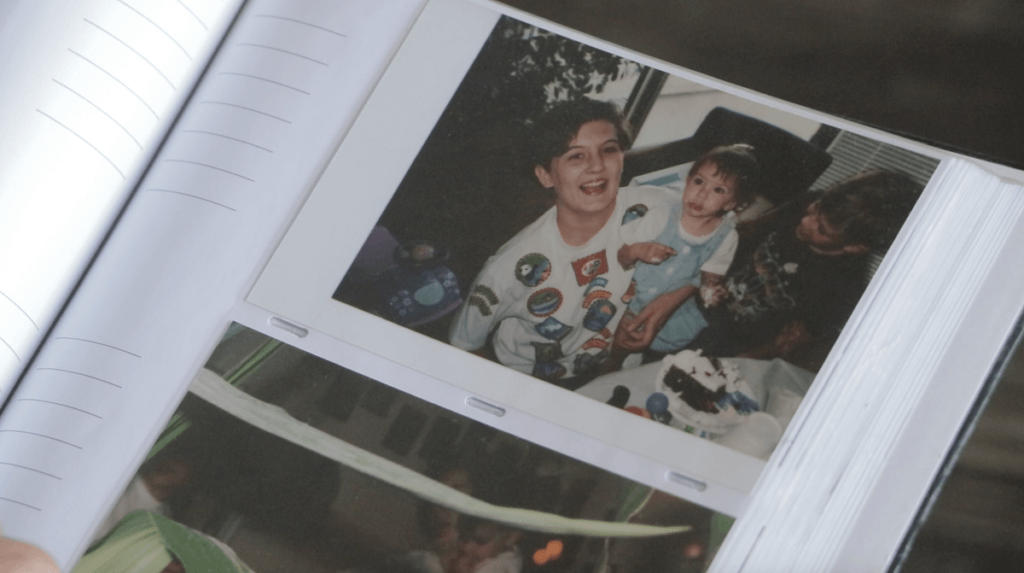

On April 18, 1995, Baylee Almon was busy celebrating her first birthday. Her mother, Aren, a 23-year-old single mother at the time, celebrated at their apartment in downtown Oklahoma City with cake and a few friends. They enjoyed the party through the afternoon, not thinking what the next day would bring.

On April 19, 1995, Baylee would be killed in the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.

She, along with 167 other individuals, lost her life that day due to an explosion orchestrated by Timothy McVeigh. McVeigh parked a van containing over 5,000 pounds of explosives in front of the building. When the bomb detonated, the blast destroyed most of the nine-story federal building and damaged at least 300 other surrounding buildings. Nineteen children in total were killed in the blast, as most of them were in the building’s daycare center.

‘This picture is going worldwide’

Domestic terrorism still a threat

Twenty-three years after the Oklahoma City bombing, the United States still experiences acts of domestic terrorism and violence every year. Most recently, the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School on Valentine’s Day of this year saw 17 students gunned down. On Oct. 1, 2017, Stephen Paddock opened fire on a concert crowd in Las Vegas with automatic rifles, killing 58 concertgoers and wounding over 500 more.

Homegrown radical terrorism remains very much a threat. Since 9/11, 47 percent of deaths that occurred because of domestic terrorism committed by far-right extremists. Until the Orlando Nightclub Shooting in 2016, in which an American-born man who had pledged allegiance to ISIS shot and killed 49 people, the number of deaths as a result of domestic terrorism by far-right extremists in the United States outweighed those committed by jihadist extremists.

“You’re never going to completely stop terrorism, whether it’s local, a lone wolf or international,” said Bill Citty, the Oklahoma City Chief of Police. “Prevention is the key to any type of incident. We have a duty to do due diligence and collect information.”

Directly after the bombing, Almon (now Aren Almon-Kok) found herself in an uncommon situation. She, along with Baylee and now-retired firefighter Chris Fields, gained international popularity overnight the day after the bombing. Minutes after the blast, Fields responded with his squadron to assess damage and perform triage. It was in the middle of the chaos when Fields was handed an infant and told to evaluate her sign of life.

That infant was Baylee. A credit officer at Liberty Bank in Oklahoma City named Charles Porter had rushed to the site with his camera and snapped the moment Chris cradled Baylee, looking down at her body. Porter would go on to win a 1996 Pulitzer Prize for his photograph, and Fields, Baylee and Aren became instantly famous.

“That night, I think I told one guy, Mike Walker, who was a firefighter under me back then, that I had a dead baby,” Fields said. “We got a call from our dispatch office, and he told me he had been faxed a photo from the Associated Press. Right before he hung up, he said, ‘This picture is going worldwide.’”

Thrust into the spotlight

The next morning, Fields and Baylee were on the cover of every major newspaper, including the New York Times, The Oklahoman and Newsweek. For both Fields and Almon-Kok, dealing with the hounding media while publicly grieving were far from easy.

“I struggled with that at first. I didn’t like being singled out,” Fields said. “I had to get [the police] to run reporters off from my house. They would go and ask my neighbors where my kids went to school. It was crazy.”

After the media discovered Almon-Kok was Baylee’s mother, she remembers being overly cautious to avoid scrutiny when she went in public.

“I had to be really careful,” Almon-Kok said. “I didn’t go out in public unless my hair and makeup were done, and I didn’t smile in public because I saw the way they did people. And it was mean. We were young, and a lot of us mothers that lost our children were young.”

An uncommon bond

After the bombing, Almon-Kok reached out to the fire department in hopes of meeting Fields. Fields knew that meeting Almon-Kok would be extremely difficult, but he needed to talk to her about him being the last one to hold Baylee.

“The first thing she did was thank us,” Fields said. “She thanked us for getting her baby out because she knew the outcome. She was strong. She did more comforting of me … than we did of her.”

After their initial meeting, the two participated in countless interviews together and established a friendship that still lasts today. Fields and Almon-Kok still are asked to do interviews on the anniversaries of the bombing, making the pair relive the event almost every year. This year, Baylee Almon would have been 24 years old.

Almon-Kok: ‘A loss I can’t get away from’

Fields and Almon-Kok still maintain a correspondence and see each other frequently. Fields has overcome PTSD and leads a quietly retired life, while Almon-Kok lives in a downtown apartment building with the Oklahoma City National Bombing Memorial in eyesight from her balcony. Every anniversary brings more interview requests, and the photograph of Fields and Baylee always makes its way into conversation.

“A lot of the parents that lost children took their losses out on me because they thought that Baylee got all of the attention,” Almon-Kok said. “But they didn’t stop once to think that I had to see my daughter dead every single day. It’s a loss I can’t get away from, even if I tried.”