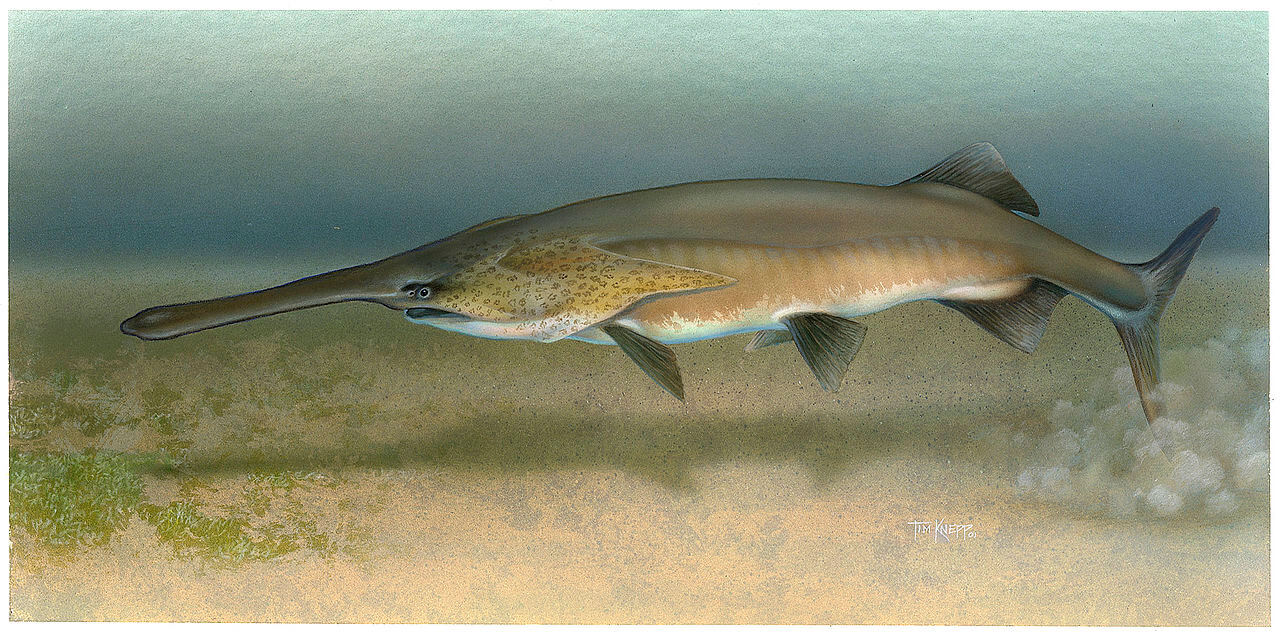

Anglers from around the country have descended on Grand Lake in hopes of catching a paddlefish before processing season ends this month. Not only have paddlefish become a popular catch in northeastern Oklahoma, sales of paddlefish caviar have pumped millions of dollars into the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) over the years.

With all of the success, it’s easy to forget that human hands could have accidentally obliterated its populations a decade ago.

“Fishermen were coming and, man, they’re saying this is great,” said Brandon Brown, supervisor of the DWC’s Paddlefish Research Center in Miami, Oklahoma. “This is the best fishing we have ever seen anywhere for paddlefish. And they think it’s never going to end.

“The public [thought], ‘This is fantastic,’ but [biologists could] look down the road a couple years and see this big storm brewing on the horizon.”

Brown said a lack of generational diversity threatened to decimate his fishery.

The prehistoric fish, which live about 15 to 20 years in Oklahoma, reach sexual maturity around age 8. Brown said biologists, using a method of studying the animal’s jawbone, calculated the majority of paddlefish in the area were about 10 years old at the time.

With a population that had been sexually mature for only about two years, and being a species that needs a narrow mix of temperate weather and rainfall to successfully spawn, scientists communicated with anglers the need to regulate fishing in Grand Lake. The result is what Brown calls one of the most unique fisheries in the world.

Brown: Caviar ‘a fortunate byproduct’

Anglers, under direction from the DWC, are allowed to keep only two paddlefish annually. No person is allowed to take more than three pounds of roe. The DWC sells the rest to fund its research.

Brown said those who focus too much on the recreational or culinary aspects of the fish are missing the big picture. He said his fishery’s paddlefish population is stable, but not a lot of fisheries around the country can say that.

“The caviar is a byproduct. It’s a fortunate byproduct,” he said. “We want to make sure people know that the real value here is this unique fishery that doesn’t exist on this scale anywhere else. I mean this a naturally reproducing, self-sustaining paddlefish population.”

Chef: Caviar ‘ethereal and emotional’ to consume

The culinary brain behind Nonesuch, a 20-seat tasting-menu restaurant that relies on Oklahoma-sourced ingredients, acknowledged the importance of Brown’s work.

“It’s obviously super important if you are interested in the preservation of ingredients and the creatures that live in our woods, lakes and streams,” said Colin Stringer of Nonesuch in an email. “There is a major poaching problem for paddlefish in this country. Our state is one of the few that has set up a system where the harvesting of the fish actually contributes to a conservation fund. It’s actually working and considering our state isn’t the most environmentally friendly, it’s pretty great.”

Stringer, who described paddlefish caviar as creamy, earthy and smooth, said eating roe has cultural value that shouldn’t be overlooked, either.

“People have been eating fish eggs as long as they have been eating fish,” Stringer said. “It’s an ethereal and emotional thing to consume, one that should be preserved for generations to come.”

Stringer said the existence of paddlefish in a landlocked state is positive. Though regulations prevent him from buying caviar directly from Oklahoma vendors, Stringer buys paddlefish caviar that was harvested in Oklahoma from out-of-state vendors.

“My culinary focus, as far as serving food to the public is concerned, has been on local ingredients,” Stringer said. “I have very little access to flavors that are seafood-like, so using caviar that is from Oklahoma gives me great options.”

Paddlefish angler: Other states should adopt Oklahoma’s regulations

William Bode, who helps run the Facebook group Oklahoma Spooners, likes the challenge of catching paddlefish but has no taste for their eggs.

“I take the eggs home in the fish, but I dispose of them,” he said. “Don’t eat them.”

Bode, who lives in Perry, Oklahoma, likes the current regulations and wouldn’t mind seeing other states adopt a similar system.

“What good does it do for us Oklahomans to only keep two per year when bordering states can keep two per day, for 30 days?” Bode said. “That’s a good way to end the population for future generations of anglers.”

In this regard, Oklahoma’s fisheries are special.

“There’s just not another one like it,” Brown said.

Paddlefish processing lasts from March 1 to April 30.