The Last Defense documentary series focuses on death row inmates who seem to be innocent. In episodes five through seven, the series presented a powerful case that Julius Jones, a former John Marshall High School honors student, did not receive a fair trial in the horrible 1999 Paul Howell murder case. Jones was subsequently sentenced to death.

The Howell murder was doubly sickening in that he was an innocent family man, shot in his Edmond driveway when the family’s Suburban was carjacked; his children were in the backseat at the time. Not surprisingly, the horrific murder prompted a hurried effort to solve the case.

As ABC reported after the murder, “fear was almost palpable” in Edmond. Moreover, this was a time when the Oklahoma County District Attorney, the late Bob Macy, was listed as one of America’s top-five deadliest prosecutors. This meant that there were not enough experienced death penalty-defense lawyers to meet the demand. Jones’ lead attorney, David McKenzie, told ABC that he lacked death penalty experience and had an overwhelming case load.

Neither did the jury hear from two inmates in the county jail – whose sentences meant they had little or no motivation for lying – who said that co-defendant Christopher “Westside” Jordan told them that he, not Jones, killed Howell.

Defense attorney later admits to doing ‘terrible job’

ABC reconstructed the key to the prosecution: how the stolen Suburban was found near the garage of Kermit Lottie, a convicted felon and longtime police informant. Lottie, Jordan and Ladell King, a notorious trafficker in stolen vehicles and an informant, claimed that Jones committed the murder.

A video in a nearby store also showed that Jones was in Lottie’s neighborhood around the time that the disposal of the vehicle was discussed. Although he had an explanation as to why he was near the shop, Jones admits that he was wrong to be there, hoping to make some money but not yet knowing of the murder. Last, Jones had four witnesses: his parents, brother and sister (the latter two were also my students). They claimed that Jones was visiting them when the murder occurred.

None of this exculpatory evidence was presented in court by Jones’ defense team. Moreover, his attorney acknowledged to ABC he did a “terrible job” of cross examining Jordan, who had repeatedly contradicted himself.

Free Julius Jones rally

6:30 p.m. Tuesday, July 31

State Capitol,South Plaza

The documentary also described how Jones’ “inexperienced and overwhelmed” defense team made another error. The victim’s sister “said the killer’s hair stuck out an inch from underneath the stocking cap,” but Jones’ hair was “closely cut.” Two photos of Jones from that week were not presented to the jury. ABC reported, “Jordan, meanwhile, wore his hair in cornrows that stuck out at the sides.” The defense’s case was based on cross-examinations, and it was a mistake to just use words instead of presenting the jury with photographic evidence. As the jury foreman told ABC, he doesn’t remember anything about hair sticking out.

Murder weapon, bandanna constitute most important evidence

In an article from July 19, ABC quoted Amanda Bass, an assistant federal public defender:

“Both Ladell King and Christopher Jordan were directing the police’s attention to the home of Julius Jones’ parents as a place that would have incriminating items of evidence,” Amanda Bass said. “Chris Jordan was in the back of a police vehicle talking to detectives who were telling people inside the home where to potentially look.”

Inside Jones’ parents’ home, police found a gun wrapped in a red bandanna tucked inside an upstairs crawl space. Jones’ attorneys said the evidence police found could have been planted by Jordan the night after the murder.

So, the murder weapon and the killer’s bandanna remained hidden in the Jones house until it was found by the police two days after the crime. This was also after Jones realized that King had named him as the trigger man. If Jones had committed the homicide, and he knew the murder weapon was in his house, would he have left it there?

Regardless, no definitive link could be made about the gun and the bandanna without a DNA test, which the district attorney’s office refused to conduct. (The district attorney’s office has subsequently agreed to a DNA test of the bandanna.)

RELATED

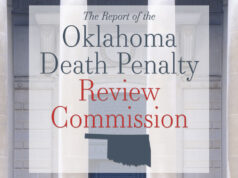

Racial bias on the jury goes unchecked

During part two, Dale Baich from the Office of the Federal Public Defender presented evidence that the prosecution dismissed black jurors for reasons that did not lead to white jurors being removed. The trial attorney, McKenzie, protested that, even then, legal precedent prohibited such tactics, but, “as is the practice in Oklahoma County, justices let the prosecutors get away with it.”

Now the Innocence Project has an even better precedent and solid evidence of the pattern of racial discrimination in the Oklahoma criminal justice system. ABC “tracked down one of the original jurors on the case, who told them a disturbing story about racial bias in the deliberation room.”

“I was a juror on the case,” this juror explains during one episode. “And this thing has weighed on me for a long time. What happened was, several of us from the jury were getting on an elevator. This was well before deliberations. And one of the jurors said, ‘Well, they should just take that n—– out back, shoot him and bury him under the jail. It didn’t matter what happened, this was a black man that was on trial for murder. He did it.'”

The juror told the judge about the comments the following day, but the juror was not removed, supposedly because the judge was not told that the N-word was used. An appeal of this decision was rejected.

ABC seeks my insights into Jones, Jordan as students

As a teacher at John Marshall during Jones’ and Jordan’s enrollment, I was quoted twice in part one, briefly providing my take on their character. Both were my students and basketball buddies. I said that Jones was “exactly the type of student you want.” In mentioning my mentorship of Jordan, I said that I did not see him as a tough person but as someone who sought a reputation as one. Also, In part three, I recalled contemporary experiences at the home of the Jones family as well as commented on the history of white flight from Oklahoma City and what the tragedy taught me about racism.

We at John Marshall thought the following the scenario was most likely: As Bass explained, “Unfortunately in our criminal justice system … the first person to be interrogated and to talk to the police who tells the police the story can be the one who gets the deal.”

Jordan’s attorney, Billy Bock, said that the interrogation of his client lasted for hours, as he was improperly required to wait for the statement to end. Bock was “amazed” by that “blatant disregard for the law.” By the way, during this interview, Jordan repeatedly contradicted himself.

ABC: ‘Oklahoma is at risk of executing an innocent man’

When watching the series, I kept asking whether I was wrong in not getting more involved. As Jones now admits, he had participated in some criminal behavior of which I was unaware. Even so, I’m a former legal historian, and my reading is that ABC is correct in concluding, “Oklahoma is at risk of executing an innocent man.”

And that leads to an insight that the district attorney’s office’s seasoned prosecutors seemed to understand better than inexperienced public defenders: The jury foreman told ABC that, in a case like that one, you “go with your heart more than anything else.” The juror trusted “what you felt in your gut.” When delivering the verdict, the juror “felt right.”

We all need to ask ourselves why it felt right for the criminal justice system to trust the testimony of three repeat felons with so much to gain and not the words of a responsible middle-class black family. Why would it feel right to repeatedly re-elect a prosecutor like Bob Macy, despite his long record of perpetuating the worst injustices of Oklahoma’s criminal justice system?

The DNA test could solve this case. Regardless, we still need to engage in some soul-searching about the way that our criminal justice system operates, especially in high-profile cases where a young black man is accused.

(Correction: This piece was updated at 7:25 a.m., Tuesday, July 31, to list the occupation of Amanda Bass correctly. NonDoc regrets the error.)