(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Paul Monies of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms. Whitney Bryen also contributed to this report.)

Five years ago, Pauls Valley General Hospital became a poster child for struggling rural hospitals.

After a plan by its management company to purchase the hospital fell through, the Pauls Valley Hospital Authority filed for bankruptcy to restructure its debt. Many in the 6,000-person community wondered if their hospital would survive. Local leaders scrambled to find a new path to stability, knowing that loss of the 64-bed hospital would endanger residents’ health, eliminate hundreds of jobs and make Pauls Valley a less appealing place to live or locate a company. (The hospital currently has 130 employees.)

Now the Pauls Valley Regional Medical Center, the facility’s new name, again is in financial distress and has become a symbol of struggling rural health care. CBS Morning News reportedly is sending a crew to Pauls Valley to report on the crisis.

Yet this time, approaches to rescuing the hospital are unorthodox. They range from seeking online donations on a GoFundMe page to buying up licenses for 28 nursing homes last year, most in other cities, to possibly secure more federal money. Whether the efforts succeed remains to be seen.

The hospital’s condition is somewhere between serious and critical.

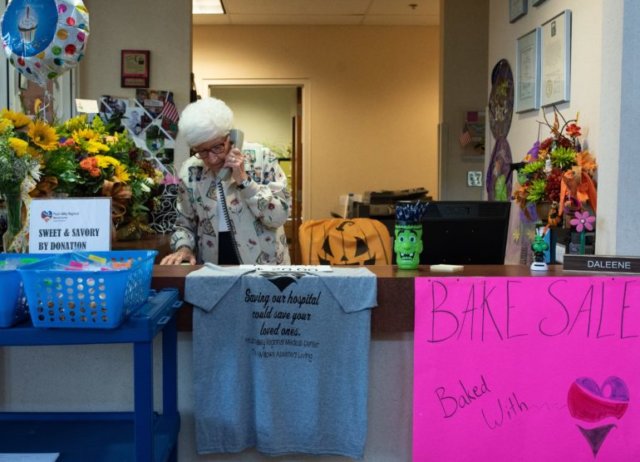

The depth of support in Pauls Valley can be seen and heard among its residents. There are bake sales, cookouts and employee pledge cards as the community rallies to help pay the hospital’s bills.

Hospital employee Kathy Craven, for example, said she would be willing to cut her work hours to keep the doors open. She has contributed and has faith that the hospital’s finances will improve.

“Some hours are better than none, and the community needs us,” Craven said.

So far, donors have contributed about $200,000, including $80,000 coming in this week from an undisclosed donor, said Frank Avignone IV, the hospital’s new CEO. Almost $4,000 has come from the GoFundMe effort.

“Obviously, it’s not a long-term strategy,” Avignone said. “There’s no way we can run the hospital on a GoFundMe donation. We started with a smaller campaign in the community to give the community a sense of participation. Long term, the hospital is going to have to get back to a point where the community trusts them. They haven’t trusted this place because of the managers that have come in here in the past.”

Avignone, whose Alliance Health Partners Oklahoma operates hospitals in Mangum and Seiling, said he’s also been soliciting donations from corporate partners and “high net worth” individuals in the area, including country music star Toby Keith. Alliance took over hospital management in July.

Bankruptcy, taxes, fees, loans and a lawsuit

Meanwhile, the Pauls Valley Hospital Authority, which owns the hospital, is involved in a federal lawsuit over management fees and delinquent loans from the former management company, NewLight Healthcare LLC.

In 2013, billing software problems and a failed acquisition pushed the hospital into bankruptcy in March 2013.

As the bankruptcy weaved its way through the court, Pauls Valley residents in 2014 approved a half-cent sales tax to support the hospital, which also had taken out large loans from a local bank. Meanwhile, patient revenue from surgeries fell as the hospital had to close its operating room for almost two years.

The hospital emerged from bankruptcy in 2016 and was expected to eke out a small profit by the next year to start building its cash reserves, according to a bankruptcy plan filed in federal court.

It didn’t quite work out that way.

NewLight, which took over management of the hospital in November 2013, said it agreed to defer its management expenses in early 2016 when the hospital was short of cash. It loaned the hospital $250,000 later that year. Several months later, NewLight loaned the hospital $1.05 million, this time under a promissory note that was secured by the hospital’s future billings, or accounts receivables. The promissory note, with interest, came due in December.

By April, NewLight still hadn’t received any payments and issued a default notice to the hospital authority. NewLight then began contacting all the hospital’s vendors to demand payments, according to a September filing in the federal court case between NewLight and the hospital authority.

“At the end of April 2018, PVHA (Pauls Valley Hospital Authority) informed NewLight that the hospital was likely to shut down, and that PVHA was trying to find a buyer or new financing,” said NewLight’s Sept. 7 filing.

SHOPP fees owed to Medicaid agency

NewLight stopped its hospital management in July, and Alliance took over. The hospital authority continues to pursue its claims of mismanagement against NewLight in federal court. Last month, a federal judge ordered in NewLight’s favor in collecting on its promissory note.

U.S. District Judge Joe Heaton was sympathetic to the hospital’s plight but said NewLight had the right to call in its note and collect on its debt.

“I frankly hate reaching that conclusion because I recognize it may well have terrific consequences for the hospital and the city, but it simply is not the case that just because you really, really, really, really, really need the money that you can take it from somebody else that has the entitlement to it,” Heaton said in a Sept. 10 hearing.

Avignone said when Alliance took over the hospital’s management, it discovered the hospital hadn’t made its required payments to the state’s Medicaid authority since April 2015. The payments are made under the state’s SHOPP program, where hospitals pay into a fund in order to attract additional Medicaid funds for “critical access” rural hospitals.

“So this facility doesn’t qualify for any SHOPP distributions,” Avignone said. “They pay into that program to support the far rural facilities, the smaller ones that have a bigger Medicaid burden.”

The hospital owes $1.3 million in SHOPP payments, including about $487,000 in penalties to the Oklahoma Health Care Authority, the agency confirmed this week.

“There’s not been a good solid set of financials presented to the hospital authority in some time, as far as we can tell,” Avignone said, according to the hearing transcript.

NewLight representatives said the company was instructed by the hospital authority board not to send the SHOPP payments because the hospital was short of cash. NewLight said it remains hopeful the hospital’s current cash crunch can be resolved.

“For five years we worked with the people of Pauls Valley Hospital Authority to bring excellent health care options to the region,” NewLight said in a statement. “In addition to bringing the hospital out of bankruptcy in January 2016, during the last two years, we’ve effectively loaned millions of dollars to PVHA as we worked with them to find alternatives that would allow the hospital to stay open while meeting its business obligations. We notified PVHA in April that the situation had become untenable for us, providing both time and options to prevent any adverse impact for patients or the community.”

In an interview, Avignone said Alliance found the Pauls Valley hospital had a collection rate on privately insured patient bills of just 11 percent. That compares to average collection rates of 45 percent at Alliance’s other hospitals, he said.

“We are trying to reestablish the facility as a center of health care, not just a hospital with an emergency room and a few beds upstairs,” he said. “We’re going to be doing more outreach. If rural hospitals are going to survive, they’ve got to change their business model. We can’t just depend on seeing a patient, filing a claim, sending it in and pray you get money back. We have to change from an inpatient facility to more of an outpatient health-care center, a medical home for our community.”

Avignone said the hospital is bringing in money now, but it’s going to pay off the promissory note to NewLight. Still, he hopes to make Pauls Valley a “destination hospital” for surgeons and primary care physicians who just graduated from medical school.

“We want to give them a chance to practice medicine, learn more and be able to do more in the rural sector, because when you’re in the big city, you’re just going to be another number on the wall,” Avignone said. “To us, you’re going to be the center of the universe.”

As proof, Avignone points to Alliance’s experience in turning around hospitals in Mangum and Seiling. He concedes neither hospital is free of troubles, but said they’re going in the right direction. Surgeries and gross monthly revenues are up in Mangum, with its collections rate rising from 10 percent to 33 percent. The smaller hospital in Seiling is a little further behind but is in “build mode” after Alliance fixed some billing issues.

“These hospitals are operating today because of the work we did, but by no means are they out of the woods,” Avignone said.

Meanwhile, in Pauls Valley, Avignone said Alliance has committed $500,000 of its own money to the hospital’s turnaround and won’t take any management fees until the hospital is in a better cash position. He said there’s too much at stake for the hospital to fail.

“This is really the only hospital that’s physically capable of delivering emergency services and the appropriate outpatient services to this region,” he said. “Otherwise, you’ve got to go to Oklahoma City.”