Facing accusations of financial impropriety, OU Vice President for University Community Jabar Shumate resigned July 23 and quickly became a public symbol of change during the first month of new President Jim Gallogly’s reform-minded tenure.

But an examination of Shumate’s three-year university employment could also help illuminate two narratives that have largely divided OU alumni into competing political camps: those who support Gallogly’s fiscal prudence and those who call predecessor David Boren a transformative president, especially as it relates to efforts at improving diversity and inclusion.

On one hand, Shumate’s 2015 hiring in the wake of national scandal — when a busload of Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity members were caught chanting “there will never be a n—-r SAE” — symbolized an overdue attempt at diversifying a campus long criticized as self-segregated. A black man who had served as OU student body president in the 1990s, Shumate said at his introductory press conference that the university has “a responsibility” to expose students to “all different backgrounds.”

Yet Shumate also stood as a lightning rod for the claims of nepotism and financial extravagance that came to dog the man who hired him: Boren, a former legislator, governor and U.S. senator who served as OU president for more than 23 years while developing a cadre of hand-picked allies in the Legislature and in administrative employ. While Boren pushed a transformation of the university’s campuses, buildings, programs and athletic facilities, he frustrated fiscal conservatives by overseeing an expansion of university debt, administrative salaries and student expenses.

Shumate’s existence at OU appears to have intersected those paradigms. Despite being a handsomely rewarded Boren loyalist, his attempts at increasing minority enrollment struggled to take hold in the thick roots of a higher education system incentivized against admitting more in-state minority students.

Boren and Gallogly briefly discuss Shumate’s duties

In the two and a half months since Jabar Shumate left the University of Oklahoma, I have spoken with numerous university staff, faculty, students and alumni in an attempt to understand the true dynamics behind the drama.

Ultimately, I decided to write this story with moments of first-person narration owing to my long history with OU: the son of faculty, a graduate myself and now an adjunct professor teaching budding Gaylord College students how to write thoughtful sentences at 8:30 a.m. Mondays and Wednesdays.

After hearing Shumate threaten legal action against the university, I submitted open records requests for documentation of his expenses and activities. After receiving those documents, I interviewed Shumate for more than two hours. In between, I also attended separate events featuring Boren and Gallogly, asking each to discuss Shumate, his mission and his activities.

Facing unexpected questions, neither Boren nor Gallogly seemed particularly thrilled to discuss Shumate, although Gallogly’s attempt to answer a third question on the subject was interrupted by interim Vice President for Public Affairs Erin Yarbrough, who suggested scheduling a full sit-down interview instead. Three weeks later, Yarbrough said Gallogly’s schedule is “incredibly full” and that she would not be able to secure an interview on the topic.

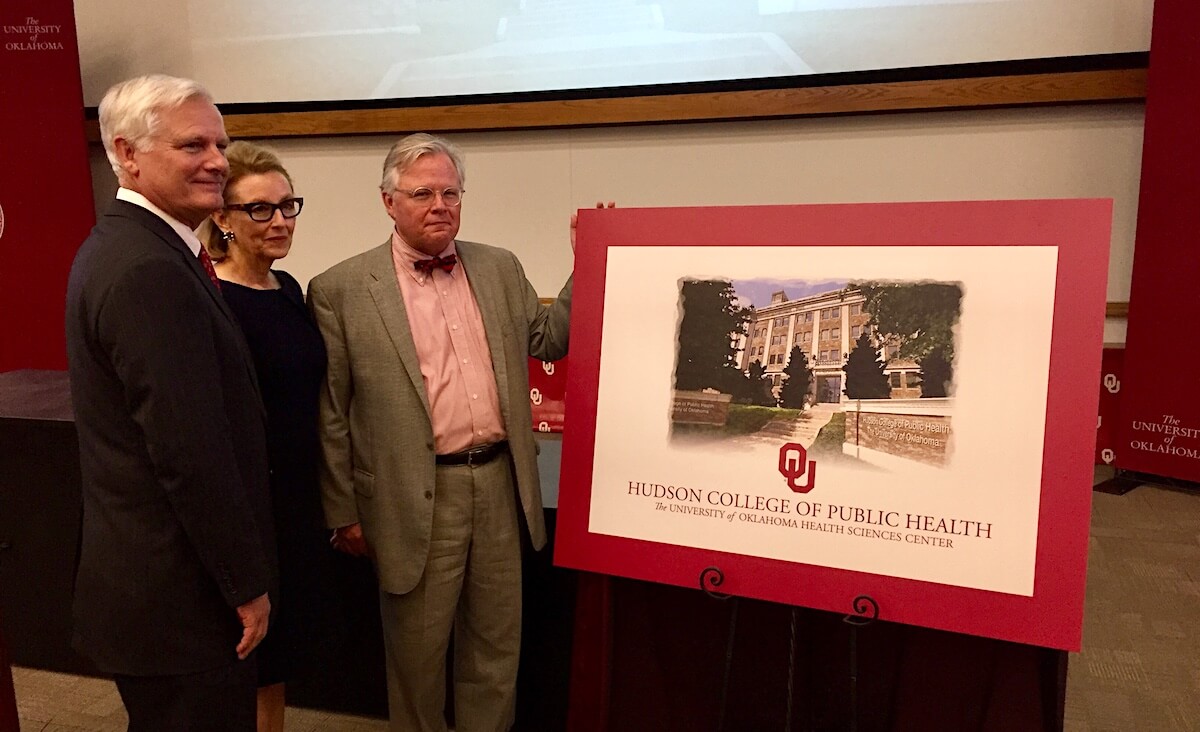

But Gallogly did briefly answer two of my questions following the Sept. 18 announcement of Cliff and Leslie Hudson’s multimillion-dollar gift to the OU College of Public Health.

“I don’t know. No, sorry,” Gallogly said when asked if he knew what Shumate’s activities were prior to resigning.

Asked what he hopes the Office of University Community will be doing in the future, Gallogly said, “That’s really easy.”

“We are out trying to recruit some people, and I hope they help me recruit the best and brightest regardless of race, color or creed,” Gallogly said. “We have a number of students on campus and want everybody to feel like they have an equal chance, that they always can speak freely and have the proper environment. That office can do all sorts of very, very positive things for us.”

After a Sept. 6 press conference where he endorsed Democrat Drew Edmondson for governor, Boren brushed off questions about Shumate’s duties.

“I just don’t want to get back into those things,” he said. “You should just look and see at his reports. I thought what he was charged with doing was interacting with the students and trying to determine if there were problems on the campus that we need to work on. An ombudsman with students on campus, that was what my charge to him was.”

Asked why university records indicated Shumate had traveled out of state — even to Belize — dozens of times in the past three years, Boren said the questions should be posed to Shumate personally.

“I couldn’t tell you details about what any single employee was doing at the University of Oklahoma because I didn’t try to keep up with every single one of them,” Boren said. “I had my turn at bat, and I’m trying not to continue to comment on administrative matters.”

Audit: ‘These two instances result in false travel claims’

Exactly what Shumate and the Office of University Community did remained largely a mystery to the public from 2015 through July of this year when Shumate said he resigned at the request of OU General Counsel Anil Gollahalli. When Shumate called a July 25 press conference to threaten legal actions against the university, he refused to answer questions.

But months later, Shumate spoke with me by phone on two consecutive days for an hour each. Shumate’s comments — along with a single 12-page accomplishment report obtained via open records request — help paint a picture of his activities, the university’s diversity challenges and how some people believe OU’s changing leadership will affect such programs.

“When you do diversity and inclusion work, it has to be championed by the leader of the organization and the institution,” Shumate said. “I felt full support from President Boren in terms of what his vision was, and I think we executed it quite well considering what his vision was. I just think leadership changed.”

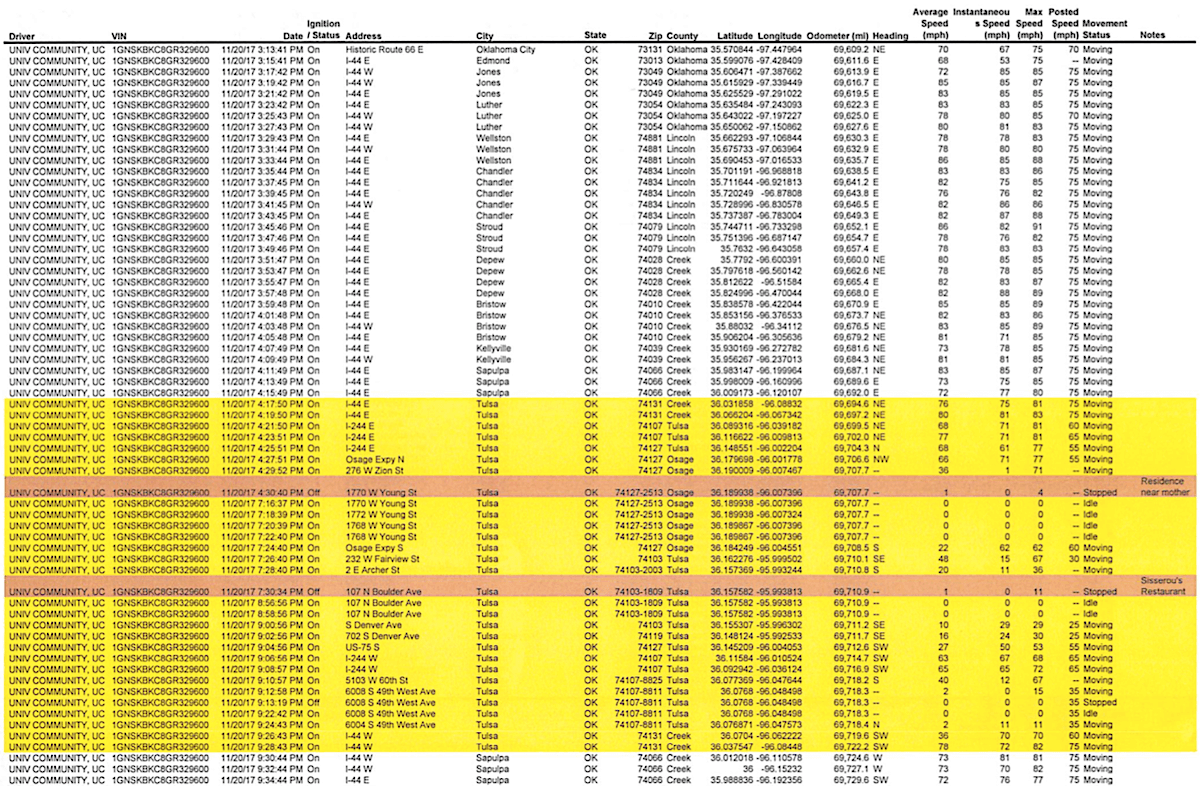

When leadership did change, conversations with administrators and reports from other media indicate Shumate gained Gallogly’s attention after questions were raised about his use of an OU Fleet Services vehicle. The university’s Internal Audit department followed up on what it called “allegations” that Shumate used a 2016 Chevrolet Tahoe for personal travel, including trips to see family in Tulsa over the 2017 Thanksgiving and Christmas breaks.

A resultant 99-page document detailed how the vehicle made those trips (see below), and it also included three other irregularities. Shumate was reimbursed $18.33 in both March and June for driving a personal vehicle to the Will Rogers World Airport in Oklahoma City for university-sanctioned travel to Austin and Lubbock, Texas. In both instances, GPS on the university’s Tahoe indicated it was parked at the airport during the dates of his travel.

“These two instances result in false travel claims, since he drove a university vehicle, but was reimbursed as if he drove a personal vehicle to and from the airport,” the audit states.

The final irregularity found in the audit of Shumate’s travel involves the purchase of gasoline at a Dallas Shell station on Oct. 22, 2017. Shumate used an OU fleet fuel card to purchase 18.6 gallons of gasoline for $62.88, which equaled a $3.38-per-gallon price. Auditors considered the price high — and possibly masking other items — after comparing Shumate’s purchase of gasoline seven days earlier at the same station: 31.2 gallons for $72.20, or $2.31-per-gallon. (Interestingly, a 2016 Chevy Tahoe has a fuel-tank capacity of only 26 gallons, though no mention of that was made in the audit report. In the fuel-purchase records provided by OU beginning July 2017, Shumate never bought more than 25 gallons at any one fill-up other than on Oct. 15, 2017.)

At his July 25 press conference, Shumate read from a prepared statement and preemptively said the documents he expected OU to release constitute “a high-tech lynching,” a phrase made famous by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas during his 1991 Senate confirmation hearing. (Thomas has been accused of sexual harassment by as many as 10 women now, though at the time then-University of Oklahoma College of Law professor Anita Hill was the primary accuser.)

Shumate: ‘In most situations, you get both sides of the story’

Speaking via phone Oct. 2, Shumate mostly declined to get into the specific allegations of inappropriate travel expenses, but he said the university did not present the internal audit document — dated July 20 — to him when he was offered termination or resignation July 23.

“What I have said publicly is that no audit was ever presented to me. The university hadn’t presented any documents. I had a three-year experience with the university with no infractions. And there was nothing given by the university to me to say there was a notice of irregularities,” Shumate said. “Nor have I seen an audit that was commissioned by the University of Oklahoma. I think in normal situations, one would be made aware of an audit or given an opportunity to clarify.”

Shumate again referenced the confirmation process for a U.S. Supreme Court justice, this time Brett Kavanaugh.

“In most situations, you get both sides of the story. That hasn’t happened. It’s just been one story sort of rolled out,” Shumate said. “For three years or for my entire legislative career, I’ve never been called into question for ethics or that kind of thing. I can at least say that. That has never been part of my professional experience at the university or prior to.”

But Shumate has seen his name printed unflatteringly in newspapers before. In 2008, a story from The Oklahoman that ultimately ousted then-House Speaker Lance Cargill (R-Harrah) for not having filed state tax returns also ensnared Shumate. First elected to the Oklahoma House of Representatives in 2004 with support from Boren at age 28, Shumate was found not to have filed state tax returns in 1999, 2001, 2004, 2005 and 2006. (In 1999, Shumate had become Boren’s press secretary at OU, a job he said he held until “about 2001.”)

“In terms of the taxes, there were some years in my earlier youth that I had failed to file, but it wasn’t that I hadn’t paid taxes. I went back and paid those quickly,” Shumate told me Oct. 2. “I don’t think that constitutes a question of me ever stealing or creating the kind of ethical situation that was comparable to what I would deem criminal behavior. I honestly made mistakes and rectified those mistakes very, very quickly.”

In 2008, Shumate also faced an indebtedness charge in Cleveland County small claims court. Records indicate OU said he owed the university $903.95, but OU ultimately moved to dismiss the case.

“I don’t know anything about it,” Shumate said of the 2008 court filing. “I don’t know. I didn’t go to court, didn’t have to hire a lawyer, didn’t have to pay, so I can’t speak to it because I don’t know anything about it.”

Connecting left hand and right hand on race

What Jabar Shumate does know is that the tasks he pursued at OU made an immediate impact and also helped lay the groundwork for greater university access by minority students down the road.

In the aftermath of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon drama — wherein Boren said an investigation showed OU SAEs had learned the racist chant at a national SAE leadership event — Shumate said he spent “a lot of time highlighting legitimate concerns that were going on in diversity and inclusion.” He said he also was trying to identify work already being done at OU to ensure “the left hand knew what the right hand was doing.”

“The university really had some significant efforts in diversity and inclusion before I arrived there. We did spend a great deal of time trying to align our work, so I’ll give you an example,” Shumate said. “The university, through the Southwest Center for Human Relations which is under the division of OU Outreach, had for the last 20 years done the largest conference on race and ethnicity in higher education in the country.

“So people all around the world came to a conference that the university sponsored every year to talk about the best and promising practices for diversity and inclusion. But when SAE happened, no one in the administration really knew that we did the largest conference on race and ethnicity in the country.”

Increasing minority enrollment ‘very, very difficult’

While he also spent time supporting student groups on campus, another primary component of Shumate’s job was to work in conjunction with the OU Admissions and Recruitment Office to increase minority enrollment at the university. That task was highlighted by the only item provided in response to my open records request for “any annual reports” that Shumate or the Office of University Community created in 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Named “Diversity Report,” the 12-page document was created in April, according to university officials, and it was part of a larger document prepared earlier in the year. The PDF’s own table of contents displays its incomplete nature:

https://nondoc.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Diversity-report-2018.pdf” height=”450px” download=”all”]The document shows a glass both half full and half empty in terms of student-body diversification. Admission applications for minority groups rose dramatically across the board from 2015 through 2017, but actual minority enrollment ticked upward with less cause for celebration.

Comparing data from 2015 and 2017, applications from African Americans increased by 768 individuals, a 67.7 percent jump. Actual enrollment, however, increased by only 18 students, a 7 percent increase between the 2015 and 2017 freshman classes.

For Hispanics, applications rose by 814 students, a 59.4 percent increase over the same period. Those numbers translated to 63 more Hispanic freshmen enrolling in 2017 than in 2015, a 17.7 percent increase.

For American Indian students, applications rose by 33 percent while enrollment rose by 12 percent.

“It is very, very difficult,” Shumate said of translating more minority applications to higher enrollment numbers. “I bet we could literally put in a very small conference room the number of students in Oklahoma who are African American and have a 26 on the ACT and have a 3.5 to 3.7 GPA that matches what I would call college-bound or college-preparatory courses.”

While OU has a “holistic” admissions process that does not mandate specific test scores, 59 percent of Oklahoma voters functionally said they do not want easier access to higher education for minorities by banning affirmative action with the passage of State Question 759 in 2012.

“That means that every minority student you recruit, their academic background must match the median outcomes you see at the entire university,” Shumate said. “We defied those odds. We showed that that could be done. I hope that work continues because I love the University of Oklahoma. We were making great headway, but I just get real concerned that maybe we will have a rollback.”

Shumate said the Office of University Community “had short-term and long-term strategies.”

“The success we saw in recruiting underrepresented students in the short term, it was obviously easier to go out and immediately start trying to recruit students who were capable of success at the University of Oklahoma, and that didn’t often mean that the abundance of those students were Oklahoma students.”

That left OU recruiting high-performing minority students from communities across the country, competing with countless universities also attempting to diversify their student bodies in terms of race and socio-economic status.

“They can go to school anywhere. They have scholarship offers everywhere. So we were very creative. I would go and see students who were, say, the caliber of national merit students. I would meet with them and their families personally,” Shumate said of his travels. “Just like we would with any scholar-athlete to say, ‘You know, you’re not going to find so many universities where university vice presidents are going to come engage with your families and you’re going to have their cell phone number.’ I had a commitment to really showing families that if their son or daughter took a chance on the University of Oklahoma, that student would thrive because they wouldn’t just be a number.”

But while Shumate was trying to recruit high-performing minority students from Texas, Georgia, Florida, Maryland and other states, he said he and other university departments were working to build avenues to OU scholarship among majority-minority schools in Oklahoma.

“We knew we had to set infrastructure in Oklahoma schools. Being a former legislator, I can tell you that — because of the main challenges with the public school system, the lack of educational funding and support (…) and the teacher turnover and the commitment — we knew that for those schools, we had to have a long-term strategy,” he said.

One example of that long-term strategy connected Shumate with Jessica Martinez-Brooks, a director of diversity enrichment programs under the Office of Admissions and Recruitment.

In 2017, Martinez-Brooks helped land a $10,000 AmeriCorps grant to fund a college-readiness coordinator position within Oklahoma City Public Schools. The position focused on increasing applications and enrollment at post-secondary institutions from students at high schools like U.S. Grant, Douglass, Centennial and Southeast, all of which feature either African American or Hispanic enrollment majorities.

“The program was extremely valuable in the fact that we had somebody within the district. There’s not a lot of kids who go to OU from Oklahoma City Public Schools or from Tulsa Public Schools,” said Martinez-Brooks, who spoke with me via phone Oct. 3. “You just don’t have very many of those kids that even have thoughts about coming to OU. Maybe a handful at best, and it’s the largest school at the (state’s largest) district. You really have to embed yourself in those schools to kind of change that culture. I think we were doing that with programs like the AmeriCorps position, and OU was investing additional dollars into that program to help with the matching funds for it.”

For the second year, OU was able to secure funding for potential expansion of the program to Tulsa Public Schools, she said, though Martinez-Brooks left OU on Aug. 31 to care for a family member dealing with a health issue.

“It’s extremely important that people see people that look like them, that are of a similar background, that come from similar schools that they come from,” Martinez-Brooks said. “I grew up on the south side of Oklahoma City, and I’ve always prided myself in helping students who come from the south side of Oklahoma City because I didn’t have those influences when I was growing up. I didn’t have that plan for college. I think this position really does help reinforce that level of support you would have if you came to OU.”

Martinez-Brooks: ‘The poor kids have the hardest time getting into college’

Shumate, Martinez-Brooks and others who spoke on background for this story identified the cost of college as one of the biggest factors preventing greater minority enrollment at OU.

“I think it’s a challenge for not just minority students these days. That’s a challenge for a lot of students these days,” Martinez-Brooks said. “We are pricing students out of higher education opportunities, and unless the state comes through and starts subsidizing like they should and have in the past, we’re just going to continue to see that.”

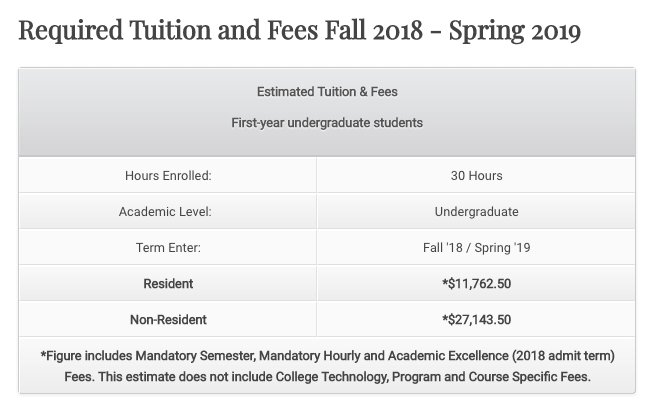

That sentiment stands as one area where Boren and Gallogly appeared to agree, though their actions differed. Boren spearheaded massive scholarship endowments through the OU Foundation, but ultimately tuition and fees rose in the majority of years, with decreased appropriations from the Legislature only exacerbating the pressure for student-based revenue. (Tuition for out-of-state residents is nearly 250 percent higher than for students from Oklahoma.)

Under Gallogly’s leadership, however, the university did not raise tuition this year for the first time since 2013. Instead, he has told reporters and the university community that his administrators have found “very significant opportunities to save money.”

Martinez-Brooks said that while financial aid can be available for students in theory, bureaucracy and university rules — such as the complicated requirement that most students live on campus as freshmen — act as roadblocks.

“There’s a million things and a million obstacles that we put in front of students just to get financial aid,” Martinez-Brooks said. “The poor kids have the hardest time getting into college. There may be some money out there for them, but they’ve got to have so much information, so many documents.”

Gallogly would appear to agree, as he was cited by K.S. McNutt of The Oklahoman as saying tuition and fee increases resulted in students paying 30 percent more for their education than they expected to when they enrolled.

“That’s a heavy burden on you and your families,” Gallogly said at a September town hall meeting covered by McNutt. “That keeps our university out of the reach of so many students.”

At the meeting, Gallogly reportedly discussed his scaling back of massive scholarships for National Merit Scholars. Tuition waivers plus stipends recruited thousands of high-achieving students, and the program allowed Boren to repeat an infamous tagline in television commercials during football games: OU is number one in the nation per capita for National Merit Scholars among public universities.

“The cost was astronomical — millions of dollars,” said Gallogly, who moved to reduce technology stipends, eliminate housing stipends and require out-of-state National Merit Scholars to pay some tuition.

According to an Oklahoma Watch article, OU spent $28.7 million on the National Merit Scholar program for the 2017-2018 fiscal year.

Shumate said he hoped the National Merit Scholar program changes might foreshadow a “re-shifting or retooling” of scholarship dollars toward supporting in-state students who qualified for OU but fell short of National Merit Scholar status. Still, he said the National Merit Scholar program assisted in the recruitment of high-achieving students.

“Any time we flagged a student who was National Merit in state or out of state who was underrepresented on our campus, I called or made personal contact,” Shumate said. “I sometimes flew to their community. Sometimes we had them come to our campus and personally host them for a tour. Because before I arrived, the university wasn’t really paying attention to (the fact) that we had students both in-state and out-of-state who were National Merit Scholars that we were not paying much attention to.”

Boren: ‘I think you have to keep things in perspective’

When Gallogly officially began work Monday, July 2, he made headlines by reducing the number of executives who report directly to him and terminating six employees before noon. Among those let go were Nick Hathaway (vice president for administration and finance), Chris Kuwitzky (chief financial officer) and Clive Mander (chief audit executive).

“You saw that, on day one, we said the CFO is gone, and (the) auditor is gone, and the head of the administration is gone,” Gallogly told News 9‘s Alex Cameron in an interview about OU’s financial situation. “I think the culture was broken, but we’re in the process of fixing those things now.”

Gallogly told News 9 that he quickly discovered that OU was facing a nearly $15 million operating shortfall for the upcoming fiscal year and that the university has about $1 billion in bonded debts.

“I’m not here to pass blame to anybody, I’m here to help fix problems,” Gallogly told News 9. “What I’m going to do is focus on tomorrow, and to do that I have to understand a bit about what happened in the past. (…) A lot has happened (at OU), in a very, very positive way, and we can thank David and Molly Boren for those things. We need to build on that. There’s always opportunities for improvement. We’re going to make those improvements.”

Boren initially told me the same thing he told News 9: that he did not want to respond to Gallogly’s comments about OU finances. But pressed slightly, he opened up.

“I think you have to keep things in perspective,” Boren said. “Our total debt service — you look at the other Big 12 universities, you look at OSU, you look at Kansas — we are very similar. We don’t get direct state appropriations for building buildings. These other Big 12 schools, many of them don’t either, and they’ve all had to bond their buildings. It takes about 6 percent of our revenue each year to make our bond payments.”

Boren said the OU Board of Regents even adopted a policy to ensure building bonds would be paid off appropriately.

“I strongly supported the policy — that you identify a revenue stream for paying off your bonds and that that revenue stream be at least 125 percent of what the annual bond payments are so that you make sure you have more than enough money every year set aside from your budget to make the bond payments,” Boren said. “And I think if you go back and look at that, you’ll find we’ve carefully followed the policies put together between the administration and the regents to have the 125 percent stream. I think you just have to put it in perspective.”

That perspective, Boren said, should include consideration of funding cuts from the Oklahoma Legislature.

“The biggest problem of course — if you go back and look at our revenue streams, look at our cash balances — you find that they were (good) going back through most of the last 15 years,” Boren said. “When they really begin to drop off in the last two years I was president, the university got cut 30 percent — 30 percent by the state in two years. Well, do you want to just immediately cut out programs and make draconian cuts? We tried to soften it because we had some cash balances, and we tried to soften the effect of the cuts by phasing them in more gradually.”

According to a 2017 story from McNutt in The Oklahoman, state appropriations for Oklahoma higher education institutions fell from $995 million in fiscal year 2012 to $810 million in fiscal year 2017.

“You can just trace it,” Boren said. “You can trace state support, and then you see when state support went down drastically — some $60 million, for example, in the last two years — that’s when the cash balances went down. But for most of the time, the cash balances were quite healthy in spite of that.”

Shumate: ‘I’m a glass-half-full kind of person’

Three weeks after Gallogly parted ways with Hathaway, Kuwitzky, Mander, former senator-turned-OU-lobbyist Jonathan Nichols (R-Norman) and others, his team offered Shumate a decision: resign or be terminated.

Shumate resigned, leaving a job that earned him $216,699.96 for fiscal year 2016, not including health insurance benefits, retirement contributions and $10,100 in “supplemental pay.” While Shumate contends that his pay was in the lower-third of compensation for cabinet-level vice presidents at OU, the former lawmaker’s six-figure salary and extensive state-sponsored travel left many Oklahoma State Capitol insiders pointing to Shumate as an example of Boren’s controversial budgeting habits.

But Shumate said he was in a special position to help Boren continue to change the culture of a university with lingering ties to its segregated past. (Recently embattled OU College of Law instructor Brian McCall, for instance, holds the Orpha and Maurice Merrill Endowed Professorship of Law. A former dean of the law school, Merrill argued in 1948 before the U.S. Supreme Court that Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher could legally be prohibited from enrolling at OU because she was black.)

“I do know that when I was hired, I think I was uniquely qualified because I knew the university community and there was a crisis on campus,” Shumate said. “I was a known entity, not only in the state, but I had worked close to 20 years in terms of my presence on the campus and my work around the University of Oklahoma.”

The first non-Greek black man to be elected student body president in OU’s history, Shumate said Boren quietly helped diversify and integrate the Norman campus in the late 1990s when such a narrative was unpopular. Shumate said, if nothing else, he believes his criticisms of Gallogly have brought attention to the important diversity and inclusion work he hopes to see continue. (A 30-year scholar, Jane Irungu is serving as interim associate vice president for the Office of University Community.)

“I was a strong member of the university family and could start the discussion in a way that no one else could because of not just my relationships but my understanding of the university,” Shumate said. “The university was a fascinating place to be at during a time when David Boren was president. I’m a glass-half-full kind of a person, and it seems from the reports that there’s a sense that the glass is half empty. And that’s unfortunate.”