On her last day as Oklahoma’s 27th governor, Mary Fallin descended the State Capitol’s grand staircase and sat stage-left of a podium she did not take.

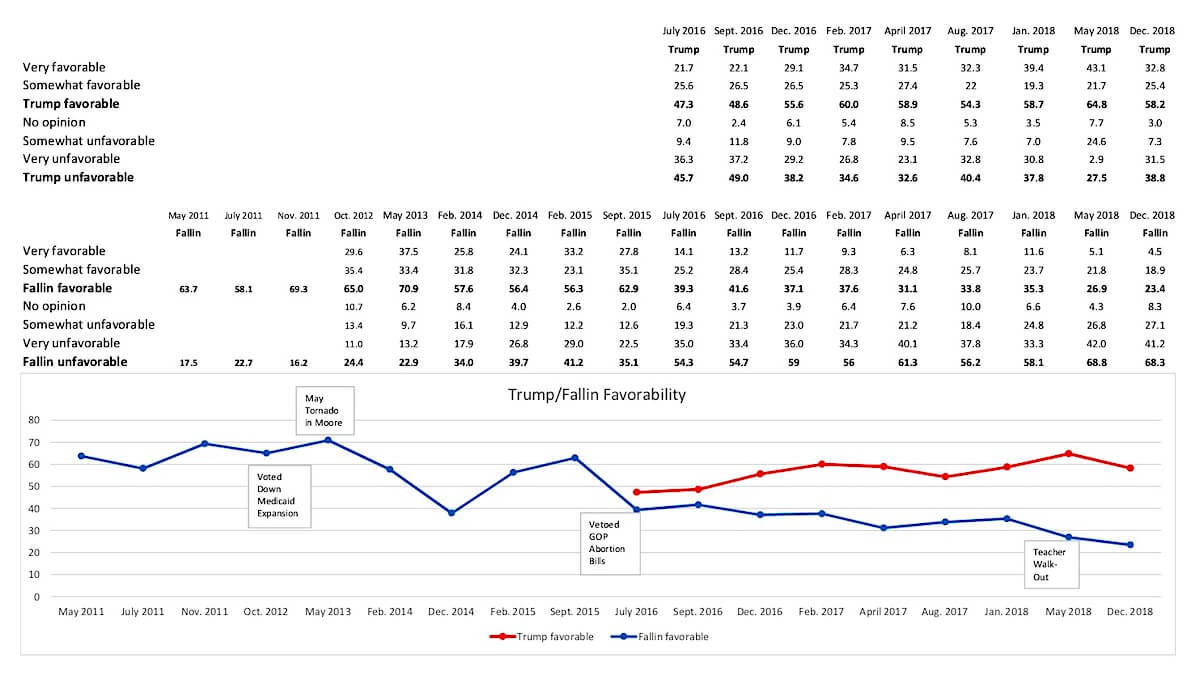

Incoming Gov. Kevin Stitt followed the state’s first female governor down the Capitol steps, which provided a final procession for a woman who never lost an election, who oversaw a series of state firsts and controversial reforms, and who departs with an approval rating barely able to get in the bar: 23.4 percent, according to SoonerPoll.com.

During the pomp, circumstance and ceremony of her fellow Republican’s inauguration, Fallin spoke not a public word, nodding and laughing as Supreme Court Chief Justice Noma Gurich underscored the Oklahoma Corporation Commission’s structural issues by reading Commissioner Bob Anthony’s comically long and constitutionally required oath of office. (Fallin created the Second Century Corporation Commission Task Force in 2017 to study and make reform recommendations for the troubled agency, but the resultant report emphasizes the challenging nature of governmental reform.)

A former legislator, lieutenant governor and congresswoman, Fallin listened Jan. 14 as her successor preached reform and efficiency to a crowd gathered at the stoop of the people’s house, its emblematic state seal glowing brightly as a symbol of the new governor’s first day.

Or of what could be the past governor’s lingering public legacy.

“I’d forgotten all the struggles since we had so many,” Fallin said of the State Capitol’s restoration in an interview days earlier. “The Capitol bond issue actually got defeated my second year in 2012, even though I kept saying, ‘We’ve got to fix the Capitol, we’ve got to fix it.'”

Trait Thompson, State Capitol restoration project manager, was working for the Oklahoma State Senate in 2012 and remembers the Senate’s proposal of $160 million in Capitol repairs falling flat in the House.

“It went down in a ball of fire,” he said. “There were a lot of fiscal conservatives in the Legislature who believed that we were going into debt and that that was a bad thing. I think some of them equated this kind of (bonded) debt to the kind of debt you see at the federal level.”

RELATED

From brain to bones, Oklahoma Capitol’s renovation impressive by Tres Savage

Thompson recalls Fallin as an advocate for the then-unpopular project, which now draws bipartisan praise as an investment in what some call Oklahoma’s top historical artifact.

“She decided early on that we were going to make this a priority and we were going to get this fixed,” Thompson said. “There’s something about the bully pulpit of the governor that has a tendency — for whatever reason — to rise above the din of the crowd. I think that did have a significant impact.”

In 2013, lawmakers tried again, logrolling $120 million for Capitol repairs into a bill cutting income taxes that the Oklahoma Supreme Court struck down. The Legislature passed the income tax cut again in 2014, and Fallin signed it in April with oil prices above $107 per barrel. That month, she also signed a measure bonding money for Capitol renovations, a bill Fallin championed and that received final passage after a chunk of concrete fell onto a House staffer’s desk. (Later, she signed another $125 million measure to finish the Capitol’s restoration after a thorough needs analysis from Thompson’s team.)

“In my mind, that’s a pretty bold move,” Thompson said of Fallin’s consistency on the Capitol renovation project. “It’s not a move that comes without criticism because I’ve heard it all in my current job. (People say), ‘You guys are just making offices pretty while all these other needs go unmet.'”

‘Something that the executive doesn’t want’

By March 2015, however, oil prices had plummeted to $51 per barrel, and financial analysts questioned the wisdom of Fallin and other Republicans who had pushed for the income tax cut in a state so dependent upon volatile commodity prices.

“Mary Fallin kind of lived and died with the state economy and with oil production and oil prices,” OU political science and journalism professor Keith Gaddie said. “And the problem is, once her approval ratings went down, it happened in the company of other events such as this open-records debacle, which just wouldn’t go away.”

Even as Fallin left office Jan. 14, that “debacle” continued to help define her legacy. Ben Felder of The Oklahoman reported Jan. 17 that “at least 24” open-records requests of Fallin’s office remained unfilled, some dating back to 2014.

“The nature of that open-records issue drove home the impression that you weren’t really sure who was in charge of the governor’s office,” Gaddie said. “You weren’t really sure who was in charge of the state, and that’s something that the executive doesn’t want to have.”

But Fallin’s gubernatorial tenure also stood as historic owing to who was in charge of the state: Republicans. Only the state’s fourth GOP governor, Fallin served as the first Republican executive with an entirely Republican-controlled Legislature, replete with infighting and turnover. During her eight years, she worked with four GOP speakers of the House and three president pro tempores of the Senate.

“The state House was just a dysfunctional institution. Several factions, and each one trying to be the most pure conservative faction out there,” Gaddie said. “That’s an impossible thing for a governor to manage.”

Still, those Legislatures passed and Fallin signed a series of initiatives — tort reform, workers’ compensation reform, pension reform and tax cuts — championed for decades by Republicans. During work on those measures, however, Fallin became the focus of substantial criticism, even within her own party.

“You’ve got critics inside the party, mainly in the Legislature, who don’t have better ideas but act like they do,” Gaddie said. “But then you’ve also got a lot of policies that really aren’t resting well with another 40 or 45 percent of the state. So while a lot of these things were accomplished, it doesn’t necessarily follow that they were particularly popular.”

But Fallin pushed for and signed other historic measures, including:

- substantial funding for Oklahoma’s neglected roads and bridges,

- components of criminal justice reform,

- the commutation of dozens of prison sentences

- and the largest tax increase in Oklahoma history, revenue from which was dedicated to teacher pay raises, increased education appropriations and state employee pay hikes.

Passed with a historic and bipartisan supermajority, that package was partially spurred when Fallin vetoed further cuts to the state budget that had been authorized by GOP leadership during a 2017 special session.

“What she did wasn’t going to be enough for the left, and she had to drag the right there kicking and screaming with the veto, and with some help from the Supreme Court,” Gaddie said of the historic tax increase.

‘If you don’t care about who gets the credit’

On Jan. 9 in a Capitol event room, Fallin made one of her final appearances as governor, meeting with several of the 30 Oklahomans whose prison sentences she commutated shortly before Christmas. She met with families and offered encouragement to those working to rebuild their lives after incarceration.

Afterward, she discussed her eight years as governor.

“Was it a challenging time? Absolutely,” Fallin said. “You start out in a national recession, you come up, but in 2014 we hit an energy bust that lasted three years. But now we’re out of that. Now we’ve got 15 percent growth in our state. We stabilized the budget, and we got the teachers a big pay raise. So I hope that we will be remembered for those things. Was it a tough time? Absolutely. But great success, and I’m more interested in getting results and finding solutions and doing the hard stuff that a lot of people haven’t wanted to do over the decades.”

She recalled a conversation from the early 1990s while serving in the Legislature.

“I still remember back in my younger days in office, an older and wise legislator told me, he said, ‘If you don’t care who gets the credit, you can get a lot of things done.’ And not to be scared to tackle tough issues if you really want to change things,” Fallin said. “I mean, the reason why I had to tackle pension systems, teacher pay, fixing the workers’ comp system, fixing 85 percent of our bridges is because it hadn’t been done in the past. So I’m proud that we were able to get those things done.”

Still, polling numbers indicate that only about one in four Oklahomans view Fallin favorably. Gaddie pointed to a particular public relations challenge that exacerbated Fallin’s image struggles.

“She would fall back on folksy charm or humor when she was uncomfortable dealing with something, and sometimes it would fall flat. That’s what it looked like from sitting over here in the peanut gallery,” Gaddie said. “I think there’s a limit to folksy charm. Folksy charm is great when things are going well, but folksy charm doesn’t help you out when everything is falling apart around you.

“If you sit down with her one-on-one for conversation, it was great. You get a sense of somebody who, criticism just rolls off her back.”

Throughout her career, Fallin faced plenty of criticism.

She received a pejorative and alliterative nickname stemming from her high-profile divorce case, and her time in the national spotlight occasionally drew ridicule. Liberals laughed when she famously snagged an autograph from then-President George W. Bush, and conservatives guffawed when she voted for the Troubled Asset Relief Program during the 2008 financial collapse.

As governor, she disappointed health care leaders by siding with conservative legislators who opposed expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. But she also disappointed conservative legislators by vetoing the permitless carry firearm bill they sent to her desk in 2018, and Republican lawmakers formed a special committee to investigate what she and staff members knew about the Oklahoma State Department of Health’s 2017 fiscal implosion. In 2015, she saw her familial arrangement make national headlines after allowing her daughter to park a travel trailer outside the governor’s mansion.

“Here’s the thing to remember about Mary Fallin: She is a Republican woman who came up in the ’80s and ’90s in politics and came up in the ’70s and ’80s in business,” Gaddie said. “She has dealt with a lot of stereotyping and a lot of misogyny. That means she necessarily has to have a thick skin, and on some level she has to not necessarily give a damn about what people say.”

‘Follow your heart and do what’s right’

What exactly people will say about Mary Fallin in 10 years remains to be seen, but her final days in office caused her to say a great deal about criminal justice reform, mental health care and addiction recovery.

“As I’ve lived my life and certainly as I became governor, I’ve seen the children who have gone into Department of Human Services care because their mother or father might be in prison,” Fallin said. “Maybe the grandparents are having to raise that child. (…) It was a circle of socio-economic problems that addiction creates in society. I just think there’s a better way of being smart on crime. These people absolutely need help, and sometimes incarceration is the only way you can break that cycle in their life. But when they’re willing and ready to make that change, I think we need to give them a second chance.”

Wednesday, Fallin’s successor appeared at an Associated Press forum and picked up the reform baton ahead of his Feb. 4 State of the State address.

“One of my big priorities is criminal justice reform,” Gov. Kevin Stitt told reporters, saying he is “open” to making SQ 780 retroactive for those currently incarcerated for drug possession.

Afterward, Stitt confirmed that Fallin had written him a letter during the transition of power.

“She left me a very nice note on my desk whenever I got there. It was just wishing me well and that she is cheering for me,” Stitt said. “She said I’m her governor now, and she wishes me nothing but great success. It was short and to the point, and I really appreciated that.”

Asked before leaving office what advice she would have for Stitt, Fallin spoke directly.

“Listen to the people. Stay engaged with citizens in the community. Seek wise counsel and put good people around you, which he has been doing,” Fallin said. “And in the end, it will always be up to listening to your own heart. He got elected because of his experience and people believing in him. And there will be times when you may know more than a lot of people know about a particular issue in the state of the Oklahoma, so follow your heart and do what’s right.”