By designating the recipients of money from his opioid settlement with Purdue Pharma, Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter has frustrated members of the state Legislature, some of whom believe Hunter violated statute and circumvented constitutional responsibilities.

Today, Republican lawmakers are expected to hear from Hunter in their caucuses, with some prepared to ask how Hunter believes he can mandate the creation of a new state foundation and designate money to it on behalf of Oklahoma citizens.

“There are multiple people who are upset about this,” said Rep. Mark McBride (R-Moore). “Most of the members have a great deal of questions. I know the speaker has had emails and phone calls and people in his office talking to him about it.”

Last week, Hunter announced a $270 million settlement with Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin. Released in 1995, the synthetic opiate is at the center of lawsuits from Oklahoma and other states who argue Purdue pushed physicians to prescribe it despite knowing its highly addictive nature. Oklahoma found itself first in line for a court date, but Hunter said the magnitude of litigation facing Purdue had left the company threatening bankruptcy, an action that would have limited and delayed the money Oklahoma could have recovered.

“The idea that there was an option to negotiate for funds that would be appropriated (by the Legislature), that just wasn’t on the table given the nature of what Purdue’s requirements were to settle,” Hunter said. “As conversations developed, their challenge was, ‘We don’t want this to be a precedent for the rest of the country. Help us think that through. Give us an idea of how we can help distinguish Oklahoma from the rest of the country.'”

To that end, Hunter said $177.5 million from the Purdue settlement would go directly to a new foundation supporting Oklahoma State University’s Center for Wellness and Recovery, a division of the university’s medical center created in 2017 for researching and treating addiction.

The settlement (embedded below) notes $102.5 million will come from Purdue while $75 million will be donated over a five-year period by the families of Dr. Mortimer and Dr. Raymond Sackler, two of the three deceased brothers who bought Purdue as a small company in 1952. An additional $20 million in addiction-related treatment drugs — like buprenorphine and naloxone — will be provided by Purdue. The company will also pay $59.5 million to outside counsel assisting Hunter and $12.5 million that will be disbursed to Oklahoma counties and municipalities.

“What we said (to Purdue) was, ‘Look, we think we’ve got a cutting-edge addiction science center here in the state that is part of a public university that has already attracted grants and financial support. We think it has the potential to be the national center for addiction science,'” Hunter said. “We had to make the best deal for the state that we possibly could given the complex considerations around Purdue.”

But Hunter, an OSU graduate who praised the Center for Wellness and Recovery’s launch in November 2017 (four months after he filed suit against Purdue and other pharmaceutical companies), said details about the new foundation authorized in his Purdue settlement remain unclear.

Hunter said no members of the Sackler family would be involved in the new foundation, and he said its governing board construction is yet to be determined.

“Those are things that we need to get worked out,” Hunter said. “I believe that the state involvement in this needs to be galvanized by having appointees from the governor, the speaker and the pro temp so there are always going to be three spots where the state leadership is involved in the decisions about the mission and about funding so that there can be coordination between private monies and the state involvement in the center.”

O’Donnell: Settlement ‘not consistent with the ethical practice of law’

Hunter answered questions about his Purdue opioid settlement from top Republican lawmakers and Gov. Kevin Stitt on Thursday afternoon. While House Majority Whip Terry O’Donnell (R-Catoosa) declined to discuss specifics of the meeting, he said he and others spoke frankly.

“I think everybody there was very frustrated and concerned about the process,” O’Donnell said. “I’m extremely concerned that any executive agency could seemingly sidestep the Legislature and circumvent the constitution and direct funds to a public trust or a nonprofit entity.”

An attorney himself, O’Donnell said no one in Thursday’s meeting questioned whether Hunter could have gotten more money in the settlement. Instead, he and McBride said legislative leaders were frustrated that they felt the Legislature had not been consulted prior to the settlement’s announcement.

“As an attorney, we are ethically responsible to report settlements and negotiations to our clients,” O’Donnell said. “Not keeping your client informed of the settlement negotiation and the details of the settlement is not consistent with the ethical practice of law.”

O’Donnell, McBride and Rep. Jason Dunnington (D-OKC) said the Legislature most closely represents Hunter’s client in the opioid lawsuit — the citizens of Oklahoma.

“We have a separation of powers for a reason,” Dunnington said. “Just because the AG felt there might be a bankruptcy and might not be a chance to get this money doesn’t make it right that there was no discussion with the body in place to appropriate this money.”

Dunnington said he would have had no problem with the OSU or OU medical centers ultimately receiving the money, but he said Hunter acted beyond the scope of his authority.

“We’ve created a precedent in which the attorney general can use the state’s resources to bring suit against corporations and then use the earnings from the case to place money wherever they would like,” Dunnington said. “That’s not the way our state is supposed to work. There is a reason why the Legislature appropriates dollars.”

Lawmakers pointed to Title 74 Chapter 2 Section 18B of state statute that defines the “duties of attorney general.” In specific, line 11 directs the Oklahoma attorney general “to pay into the State Treasury, immediately upon its receipt, all monies received by the Attorney General belonging to the state.”

“It’s in statute,” McBride said. “This is a duty of the attorney general — to pay into the state treasury immediately upon receipt, not to have the authority to give it to some nonprofit of his choosing.”

First elected in 1984, Hunter served six years in the Oklahoma House himself and said he recognizes the Legislature’s responsibilities.

“I guess I understand the concern that has been expressed by some over this not going through the appropriations process, but understand that money will not come through our office. That money will go directly to the foundation once we get that funding in place,” Hunter said. “If one of the options would have been to put the funding through the appropriations process, it would have been something that would have been agreed to out of hand.”

Hunter said that option “wasn’t on the table,” however, because it was not consistent with Purdue’s conditions for settling the lawsuit.

“Not to be flippant here, but the options were $0 and allowing Purdue to go into bankruptcy, which they were likely going to do to avoid trial,” he said, “or settling on this basis that met their condition but provided an incredibly generous investment in a state asset that now has the strong potential to be a national asset.”

Hunter wants to ‘replicate’ M.D. Anderson Foundation

Hunter said he, OSU Medical Center leaders and Purdue Pharma all want the OSU Center for Wellness and Recovery to become a national health care beacon similar to the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas. Multiple times, he said the new foundation established in his Purdue settlement should mirror the M.D. Anderson Foundation, established in 1936.

“The more we can replicate that, the more sense it makes to me,” Hunter said, emphasizing how details about that framework could be found online.

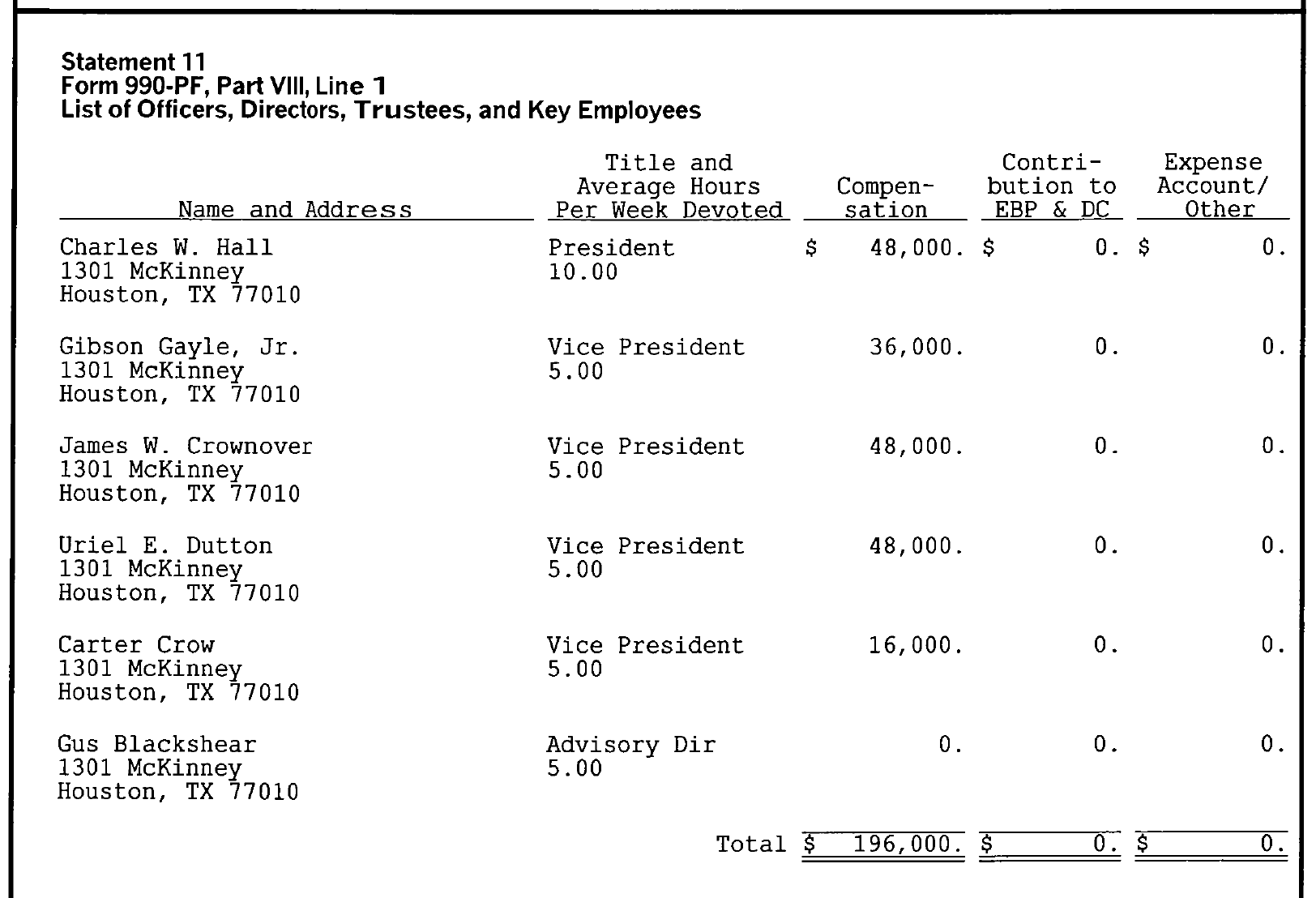

But the M.D. Anderson Foundation has not filled out its public profile on GuideStar, a leading repository for IRS and self-reported information about nonprofits. While a 2012 post on the M.D. Anderson website explains the foundation’s history, no page listing the current board membership of the M.D. Anderson Foundation appears to exist on the cancer center’s website. Six names receiving a total of $196,000 in annual compensation do appear on page 23 of the foundation’s latest 990-PF IRS form, however:

M.D. Anderson also features a robust Board of Visitors, which fundraises for the hospital’s mission of eliminating cancer. Should state leaders need more information about the board of visitors, they could turn to “life member” T. Boone Pickens and 2015 executive committee member Jim Gallogly, now president of the University of Oklahoma.

“The foundation (component of this opioid settlement) is really not clearly understood,” O’Donnell said. “We don’t know who or how individuals will be selected to that foundation board, so that’s of a lot of interest to the Legislature.”

Hunter: #okleg will be ‘integral’ in disbursing funds from other defendants

While lawmakers ruminate over whether any legislative action should be taken to address the Purdue opioid settlement or preclude similar future arrangements, Hunter said he intends to work with the Legislature while preparing for trial against the other primary defendants in his opioid lawsuit.

“There are not discussions nor is there a potential that bankruptcy is an option for any of the three. They are all publicly traded and well capitalized,” Hunter said of Johnson & Johnson and Teva Pharmaceuticals. “Because we don’t have the same complexity, because we don’t have the same tough calls to make, any settlement funds or any funds from judgements going forward, the Legislature and the governor will be integral in how we develop that architecture and how that funding is deployed.”

But some lawmakers believe those promises are not good enough, especially considering a lawsuit from New York Attorney General Letitia James that alleges the Sackler family fraudulently pulled money out of Purdue in an effort to make it untouchable in legal settlements or judgments.

“Basically, we set up an endowment for that family for them to put potentially tax exempt dollars into. This family is worth billions,” McBride said. “That may not even matter to some people because we got the money.”

Settlement between Purdue Pharma and the state of Oklahoma

Loading...

Loading...