The sheriff’s department cruiser from a rural Oklahoma county drives alone on a highway with a single deputy at the wheel and a man in the backseat.

Only an hour earlier, the man had threatened to kill himself and anyone who tried to intervene. Concerned, his family called 911. The deputy calmed the man down and eventually managed to get him in the back of his cruiser.

But their destination isn’t the nearest jail — it’s a mental health facility with an open bed. If they’re lucky, the local county facility will have space, but that’s rare. More often than not, the deputy will spend the rest of his shift and then some trying to find somewhere that can take the man experiencing a mental health crisis.

Emergency orders of detention, often referred to as EODs, are a fact of life for law enforcement who encounter mental health crises, but in rural areas they become especially tricky.

This scenario plays out over and over again in rural Oklahoma counties already grappling with wide open spaces and only a handful of deputies or officers to police them.

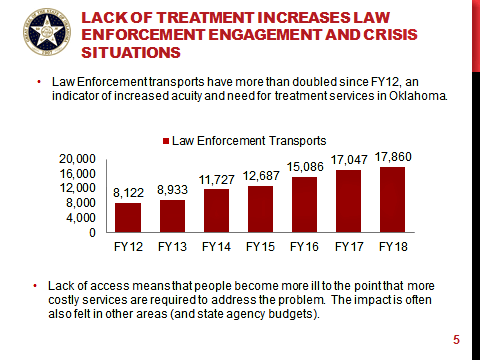

Oklahoma law enforcement agencies conducted 17,860 mental health transports in 2018. That represents an explosion over the last half decade. In 2012, 8,122 were transported, according to figures from the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse.

‘We don’t have the personnel’

Elected in 2009, Stephens County Sheriff Wayne McKinney has a lot of ground to cover. The county is 900 square miles, and he has 12 deputies in his regular patrol rotation. On any given shift, just two are on duty.

“The EODs are probably one of the biggest time consuming tasks we have,” McKinney said. “We don’t have the personnel to adequately protect our county, and then you add a situation like that which is also important, it takes a lot of manpower away.”

The challenges start when a deputy arrives at the scene, McKinney said. One of the first hurdles is understanding what is happening.

Bill Perkins, one of McKinney’s deputies in Stephens County, said most cases initiate with a call from a family member. When the deputy arrives, one of the first tasks is to assess the threat level.

“The deputy does an evaluation to determine if they meet our criteria as far as harming themselves or others,” Perkins said. “At that point, we may or may not take them into custody depending on that evaluation.”

When people are deemed to be a threat to themselves and do not agree to visit a mental health center on their own, reporting parties can sign an affidavit detailing what threats were made before law enforcement arrived. Then, law enforcement can begin the EOD process and an individual can be taken to the nearest hospital for further evaluation. Often, however, the journeys extend well outside the county line.

When that happens, McKinney said he is usually forced to call in an off-duty deputy to fill the slot. Meanwhile, at the hospital, things are rarely simple.

“The worst situations are when you have a deputy sitting at an ICU for an extended period of time like 24 or 48 hours,” Stephens County Undersheriff Bobby Bowen said. “We had one of those not long ago, and it’s a big time problem.”

Emergency rooms aren’t ideal situations anyway.

“Those emergency rooms don’t consider themselves mental health facilities,” Perkins said. “So you have a deputy on standby waiting around to see if they’re going to admit them or if they will have to take them somewhere else that could be literally hours away.”

Patients admitted to a mental health center can be held for up to 120 hours. Beyond that, a court order is needed. Perkins said Stephens County deputies have been tied up for periods as long as 24 hours at hospitals.

The Jim Taliaferro Community Mental Health Center in Lawton is the nearest facility to transport Stephens County residents in EOD situations. It’s about 45 minutes from Duncan. McKinney and his deputies said they have also taken people to Wichita Falls, Texas, and as far away as Oklahoma City.

“Texas has a pretty good system,” McKinney said. “They have a lot of facilities. We’ve taken them down there several times.”

Lawmakers who are former law enforcement have first-hand knowledge

Rep. Johnny Tadlock (R-Idabel) spent 28 years in law enforcement, including a stint as McCurtain County sheriff in far southeastern Oklahoma. He found EOD transfer problems frustrating.

“I never wanted to be rude to anyone, but my thinking when I was sheriff was, ‘I’m doing my job and it shouldn’t be my problem. You guys need to do your jobs,'” Tadlock said of the delays in getting patients admitted to mental health facilities.

Tadlock supervised about 20 deputies in his department. When an EOD required one to be used for transport, he called another deputy in. The solution created a cascading effect.

“It became a budget issue,” Tadlock said. “You’re spending all this money, and for what you’re spending, you could hire another deputy.”

Freshman Rep. David Hardin (R-Stillwell) served as Adair County Sheriff for five years.

“It came up frequently,” Hardin said at the Capitol. “The biggest problem was trying to find a bed. Sometimes we’d have to go to Wagner or Vinita. There were a couple of times where we had to go across state lines.”

Agencies can bill the state for transport costs beyond 20 miles, but it comes at a greater cost than gasoline.

“Their shift is usually over when that happens,” Hardin said. “You’re not going to get anything else out of them for that day.”

The drag on resources isn’t confined to rural areas.

“We’ve had police in the Oklahoma City area transport people hundreds of miles, so it doesn’t matter if it’s a rural or urban situation. If beds are full, they have to travel,” said Terri White, commissioner of the ODMHSAS.

Tadlock: ‘It’s the bed space’

Tadlock said the solution to the transport problem is fairly simple.

“We need the services and the bed space,” he said. “That’s where the logjam is created. That’s what we hear all the time. It’s the bed space. If that’s the excuse, it’s pretty obvious what’s needed.”

A military veteran who has advocated for better mental health care in Oklahoma, Rep. Josh West (R-Grove) agrees.

“All roads lead back to the bed issue — access to mental health treatment,” he said. “We just don’t have it. Those that we do have are closing down. So it’s going to be a huge issue, especially for rural areas.”

West recently traveled to the White House for the announcement of President Donald Trump’s executive order expanding three mental health programs for veterans.

West said the subject comes up frequently at the Capitol with other legislators, those in law enforcement and at his home.

“My wife is a therapist and a veteran, and it’s a big-time conversation at my dinner table,” West said.

Freshman Rep. Randy Randleman (R-Eufaula) is a psychologist. He’s worked with school districts across Oklahoma. Before earning his doctorate, he served as a teacher. He sees a need for more beds as well as expanded treatment options.

“There’s a massive need for more beds,” he said. “And I think there’s a massive need for outpatient mental health.”

Randleman said shrinking resources have exacerbated the problem.

“I’d like to see more services,” he said. “If you notice, we’re losing some of our rural hospitals. Having access to mental health services especially in rural areas continues to be a an obstacle.”

Outside of the need for more beds, Randleman said more mental health professionals in rural areas accepting Medicaid and Medicare would help alleviate some access problems.

Still, he said the issue is also about quality over quantity.

“What’s really scary to me is if someone does an evaluation and they’re not trained properly in those procedures,” he said. “I don’t want to see that.”

Getting ahead of problems can help reduce the need for mental health transports later on. White said the national average for investment in mental health treatment and services is about $120 per person. In Oklahoma, she said it’s $56. That sum includes substance abuse and mental health services including in-patient treatment.

“Only one in three Oklahomans in need of treatment are able to get it,” White said. “When people can’t get them, that’s when they go into crisis.”

Solutions offered regarding mental health transports

There is an effort to solve one problem associated with EOD transfers. Often sheriffs deputies have to determine who is responsible for the transport something that can be more complicated than it sounds.

When Tadlock served as sheriff he had a handshake deal with local police. If the person was a city resident the local police were responsible. If they lived outside city limits his department handled the transport.

RELATED

Mullin urges Congress to renew mental health program by Anna Bauman & Abby Bitterman

Sen. David Bullard (R-Durant) is running SB 609 which passed the senate unanimously in March. The bill would provide clarification to local and county law enforcement regarding the transport of mentally ill patients.

Under current law, the agency that “found” an individual is responsible for mental health transport. The bill changes that to the agency that “initially contacted” the individual, and it defines that to include fire departments and other public agencies.

“Every time we have to transport someone to another area, we lose that resource off the street,” Bullard said. “This bill resolves a particular issue that I had heard about from those in law enforcement who had concerns about it.”

Bullard said attempts have been made to determine if other ways of transporting those who are mentally ill can be explored, including ambulance services. The bill initially included funding for third-party transport services, but ultimately that language was stripped both for lack of funds and vendors.

“Those third parties don’t make enough from doing it, and often it can be at strange hours,” he said.

Bullard said those in law enforcement he spoke with were more concerned about clarifying who was responsible for the transport than the money.

“When I asked them what was more important — the dollars or establishing the point of contact — every one of them said they were already dealing with the dollars and that they wanted to straighten out who is responsible for the transport,” he said.

More beds could also be part of a broad solution, he said.

“I know there have been situations where an officer has contacted a facility and taken the person there only to arrive and find out that bed was taken by someone else as they were driving to the facility,” he said. “That’s frustrating.”

Technology can also help to alleviate some of the problems, at least when it comes to assessing whether a person needs to be taken to an in-patient mental health facility.

West said some deputies in Delaware and Craig County have access to tablets through a program started by the Grand Lake Community Mental Health Center that can connect them find a therapist 24 hours a day. The therapist can then help advise the officer in real time.

White said efforts like that — which were developed locally and funded by the state — are important to the overall mental health picture in Oklahoma.

But she said there is still plenty of room for improvement.

“We have great outcomes, but we’re only getting one in three people through a narrow door,” she said.