(Editor’s note: This story was authored by Trevor Brown of Oklahoma Watch and appears here in accordance with the non-profit journalism organization’s republishing terms.)

Election officials are gearing up to remove tens of thousands of Oklahomans from the state’s voter rolls — a controversial practice voting-rights advocates say can lead to disenfranchised voters.

Oklahoma is one of seven states that allow election officials to remove names from the state’s voter registration list if they haven’t voted in several election cycles and don’t respond to address confirmation mailings.

That process, which is done every two years in Oklahoma, will begin this April.

If it’s like the last voter purge in 2017, a sizable portion of the state’s nearly 2.2 million registered voters will come off the rolls.

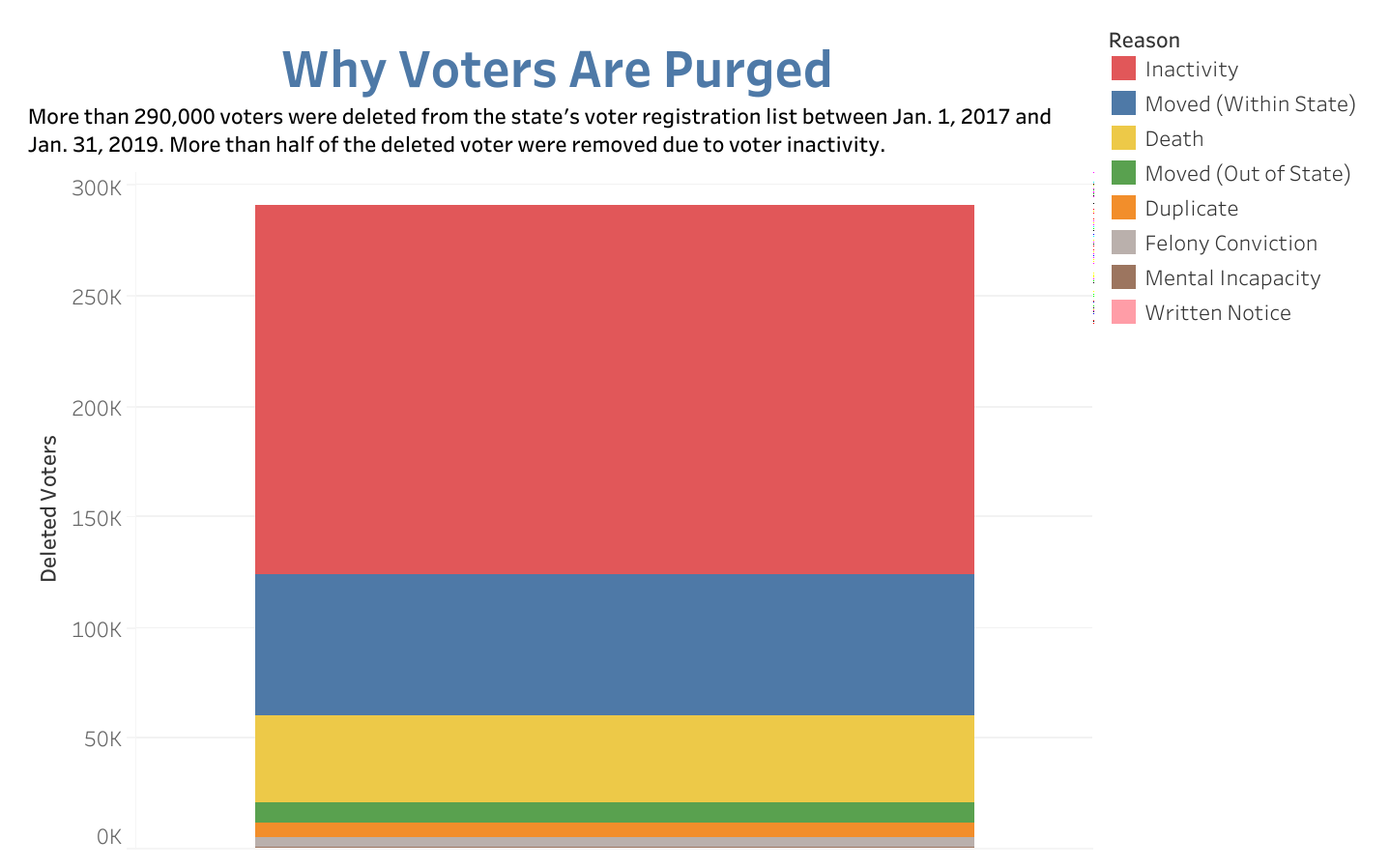

A list obtained by Oklahoma Watch from the state Election Board shows that 291,233 names were deleted since 2017. Of that amount, more than half were deleted due to inactivity. The purge of inactive voters occurs in April in every odd year.

Oklahoma State Election Board Secretary Paul Ziriax said deleting the names of inactive voters helps maintain the integrity of elections by ensuring that registration lists are accurate and up to date.

He added that voters are only removed due to inactivity after a multi-step process.

This includes when someone hasn’t voted for four general-election cycles, covering an eight-year period, and does not respond to the address confirmation notice the state sends out before listing a voter as “inactive.”

But legal challenges, controversies in other states and a new push by congressional Democrats to ban so-called “use-it-or-lose-it” voting laws has put the issue under renewed scrutiny.

“Voting should never be a use it or lose it,” said Leigh Chapman, voting rights program director for the Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a Washington D.C.-based nonprofit that lobbies for civil rights laws. “It’s a right, and we should be making it easier to vote, not harder.”

The purging process

Through a largely automated process, the state Election Board is constantly updating voter rolls when someone has moved, died, been convicted of a felony or has been certified as mentally incapacitated.

The process for removing inactive voters begins in the spring following a general election.

Before June 1, the state will send the address confirmation to voters who haven’t cast a ballot in either of the last two general elections or any state or local elections in that time period.

If the voter doesn’t respond within 60 days of receiving the letter, they are put on “inactive status” but are still cleared to vote. The voter can regain their active status at any time by voting in any election or updating their voter registration information.

But if the voter, while on inactive status, doesn’t participate in an election for two more general election cycles, their voter registration will be purged and they will need to re-register if they want to vote again.

That means the voters will be purged this year didn’t vote in 2012 or 2014 elections, didn’t respond to the address confirmation letter and haven’t voted since.

The essentially eight-year period is longer than many of the six other states that have similar laws. Ohio and Georgia, for example, allow election officials to purge voters after a six-year period of inactivity.

Ziriax said the state’s lengthier process gives voters ample opportunities to retain their voting status and voters are regularly reminded to double-check before registration deadlines to make sure they are eligible to vote.

He added that the benefit of cleaning the voter rolls and removing those who are unlikely to vote protects the election integrity.

“Voter fraud is exceptionally rare in Oklahoma and not a major issue here,” Ziriax said. “But for someone who wanted to commit fraud, the less updated your voter records are, the easier it is to do that.”

But without fail, there will be some voters who had been purged go to vote with the assumption they are still eligible and will be turned away.

“There will be someone who says they last voted for Bill Clinton or George H.W. Bush in 1992 and they’re not registered any more and they want to know why,” Ziriax said. “But I can’t control that and I can’t control what the law says.”

Oklahoma and the other states with use-it-or-lose-it voting laws faced a threat last year when the U.S. Supreme Court took up a case seeking to overturn Ohio’s law.

The court, in a 5-4 decision, ruled that Ohio’s law did not violate the National Voting Right Act, clearing the way for states to continue removing voters.

The issue was further pushed into the spotlight last year when Georgia purged hundreds of thousands of voters ahead of its contentious gubernatorial election, which Republican Brian Kemp ended up winning by a slim margin over Democrat Stacey Abrams.

In that case, as well as with other voting purges, critics argued the policy disproportionally hurts minority and Democratic voters.

Chapman said this is likely because minority groups tend to move more – raising the chance that they never received the address confirmation notice – and have faced voter suppression issues in the past.

Voter purge 46 percent Democrats, 33 percent Republicans

A review of Oklahoma’s purge of inactive voters in 2017 shows that Democrats were disproportionally affected.

Of the 167,011 who were deleted due to inactivity, about 46 percent were Democrats. Voter registration statistics before the purge, on Jan. 1, 2017, show that Democrats made up about 39 percent of all registered voters.

Republicans, meanwhile, made up about 33 percent of the purged inactive voters while making up nearly 46 percent of the pre-purge voter registration totals.

University of Oklahoma political science professor Keith Gaddie suggested one of the reasons Democrats are more likely to be purged due to inactivity is because “many elderly voters who start to become less prone to vote are more likely to be Democrats.”

“Low-propensity voters are more likely to end up purged, and they also tend to more often be independents and Democrats,” Gaddie added.

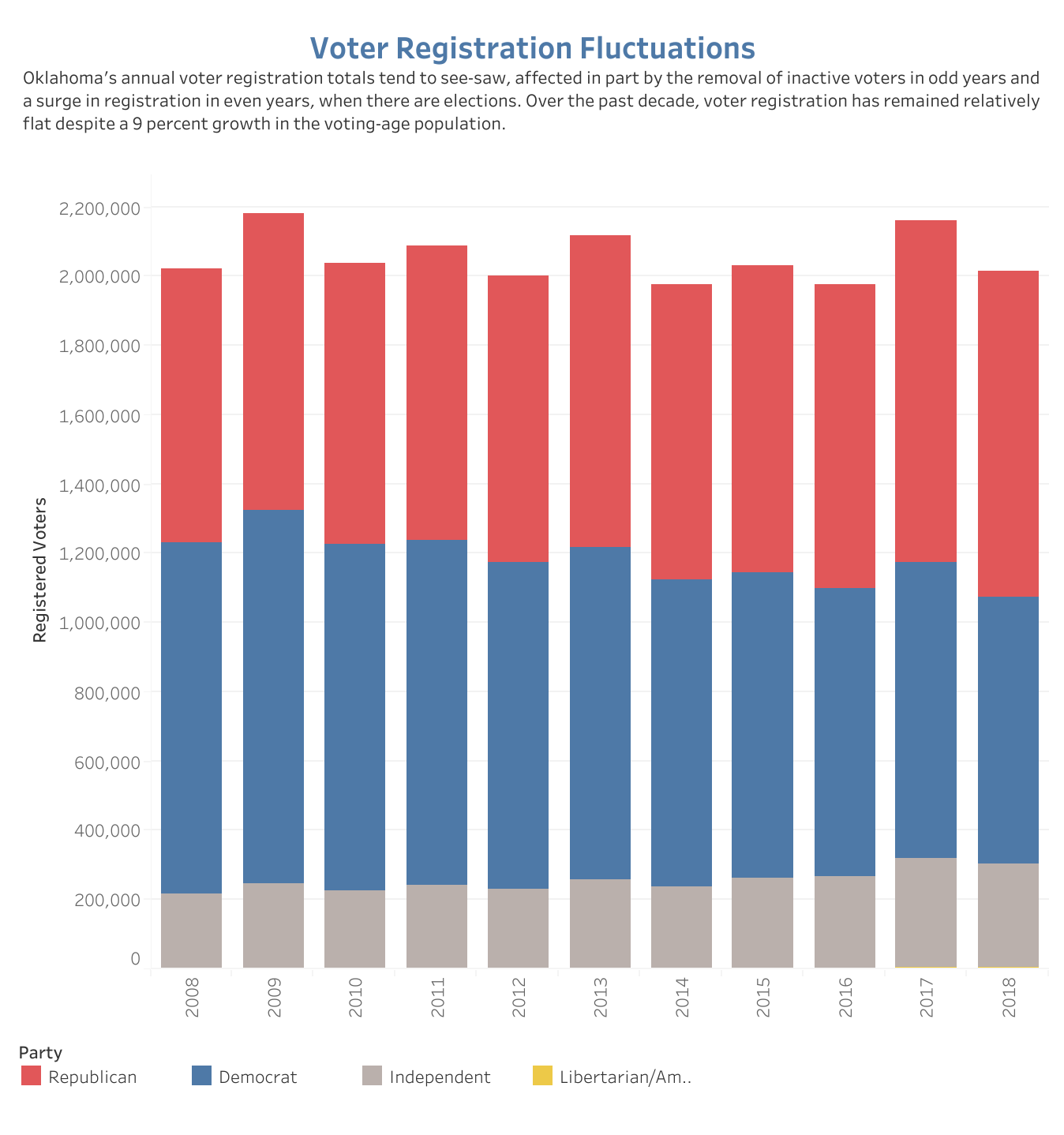

With the regular purging, the total number of registered voters tends to increase in even years, when state elections occur, and fall in odd years. In January 2008, there were 2,022,537 registered voters, slightly more than the 2,016,157 in January 2018 despite population growth, state Election Board data shows. Various factors can affect overall and party totals in voter registration. Registered Democrats have dropped by 24 percent while Republicans have gained by 19 percent over the period.

Purging ban proposed in Congress

Congressional Democrats are seeking to pass a federal law that would ban states from removing voters due to inactivity.

The bill with language to ban removal of voters because of inactivity passed the Democratic-led U.S. House earlier this year, but Senate Republican leaders have signaled they will not hear the proposal.

Chapman said she hopes the Senate will reconsider and take up the proposal. But, if there are no changes on the state or federal level, she urged voters to be proactive and make sure they are registered before voting.

“Voting is a right,” she said. “And people should have every ability to cast their ballot and have it counted.”