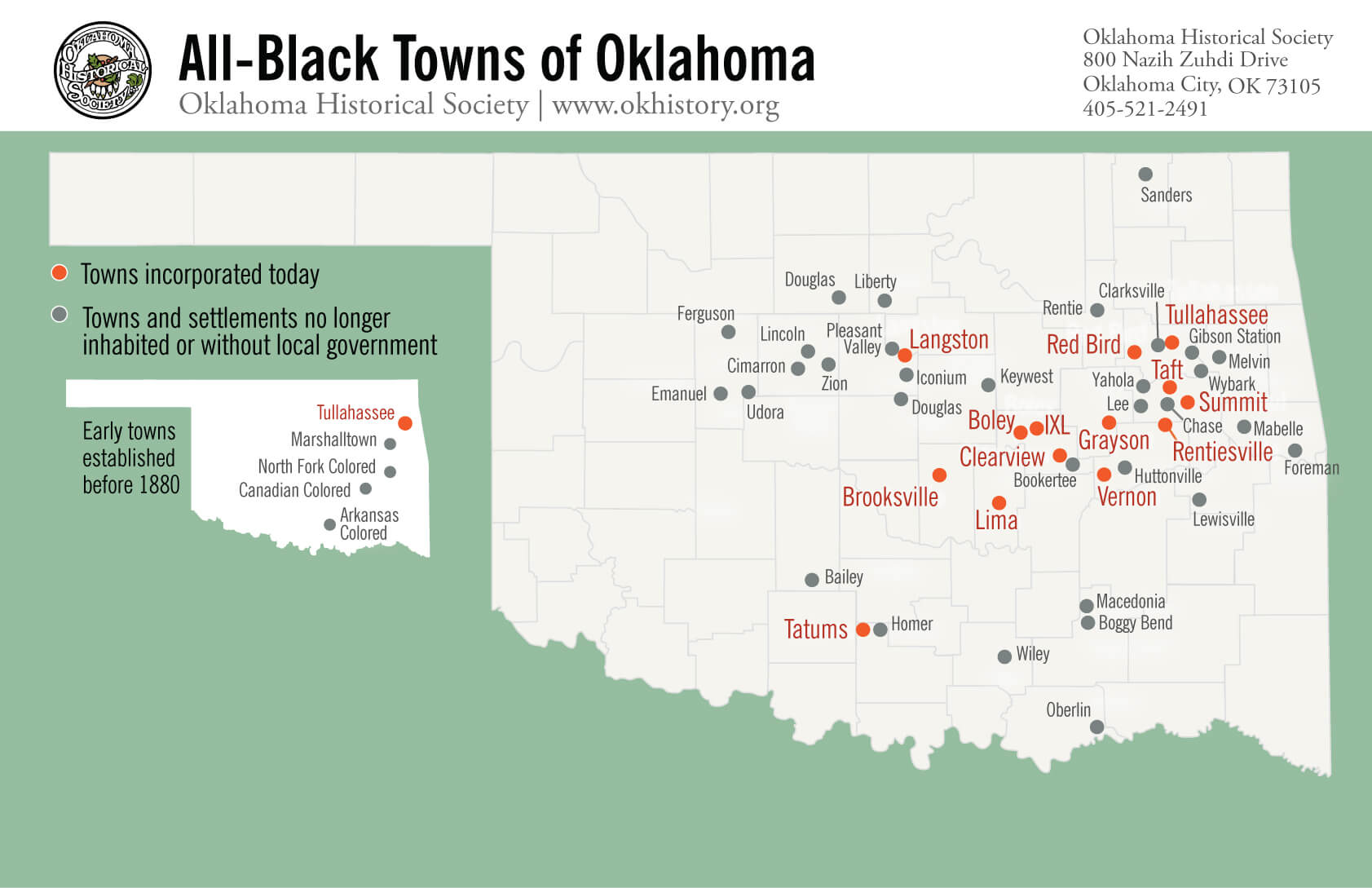

BOLEY — Thirteen historic all-black towns are still incorporated in Oklahoma. Most feature abandoned and run-down buildings, but a nonprofit group is working to preserve and revitalize the towns.

The Coltrane Group, a set of volunteers focused on revitalizing and preserving the black towns of Oklahoma, has worked to bring new life to these 13 communities by holding all-black town tours for the last four years. They are raising money and writing for grants to preserve and revitalize the towns’ most famous buildings.

“Even if it’s just to help the cemetery in that area where their ancestors are buried. Or some of their relatives are buried,” said Jessilyn Head, co-founder of the Coltrane Group. “This is an effort that begs assistance.”

Oklahoma’s first all-black towns were created in Indian Territory after the Civil War when former slaves of Native Americans settled together following the Trail of Tears. In these early towns, newspapers advertised throughout the south about land and opportunities, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

“It was advertised that Oklahoma (…) was a wonderful place with rich soil, great land, great opportunities,” said Jessilyn Head.

A new hope for black Americans

Between 1856 and 1920, more than 50 all-black towns were founded in Oklahoma, totaling more than anywhere else in the country and creating a mindset that Oklahoma could be a land of opportunity for black Americans.

The most prominent towns — such as Langston, founded in 1890 — were created after the Land Run of 1889. Advertising in black-owned newspapers brought even more people to the towns, creating a large growth before Oklahoma reached statehood.

Just one day before Oklahoma became a state, an ad in The Muskogee Cimeter, a black-owned newspaper, proclaimed excitement and hope for blacks in Oklahoma, according to a magazine by the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department tilted Long Road to Liberty.

“To our colored friends throughout the United States, we send you greeting,” the ad said on Nov. 15, 1907. “The Indian Territory and Oklahoma are now a new state. Thousands of our native people are land holders, and have thousands of acres of rich lands to rent and lease. We prefer to rent and to lease our lands to colored people. Our terms will be found reasonable. You are invited to come and share and enjoy our lands and our prosperity in the new state of Oklahoma.”

Boley ‘by blacks, for blacks’

In Oklahoma’s all-black towns, former slaves and their children found life to be free from prejudice and brutality by not having their population mixed like other communities in the South and Midwest, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

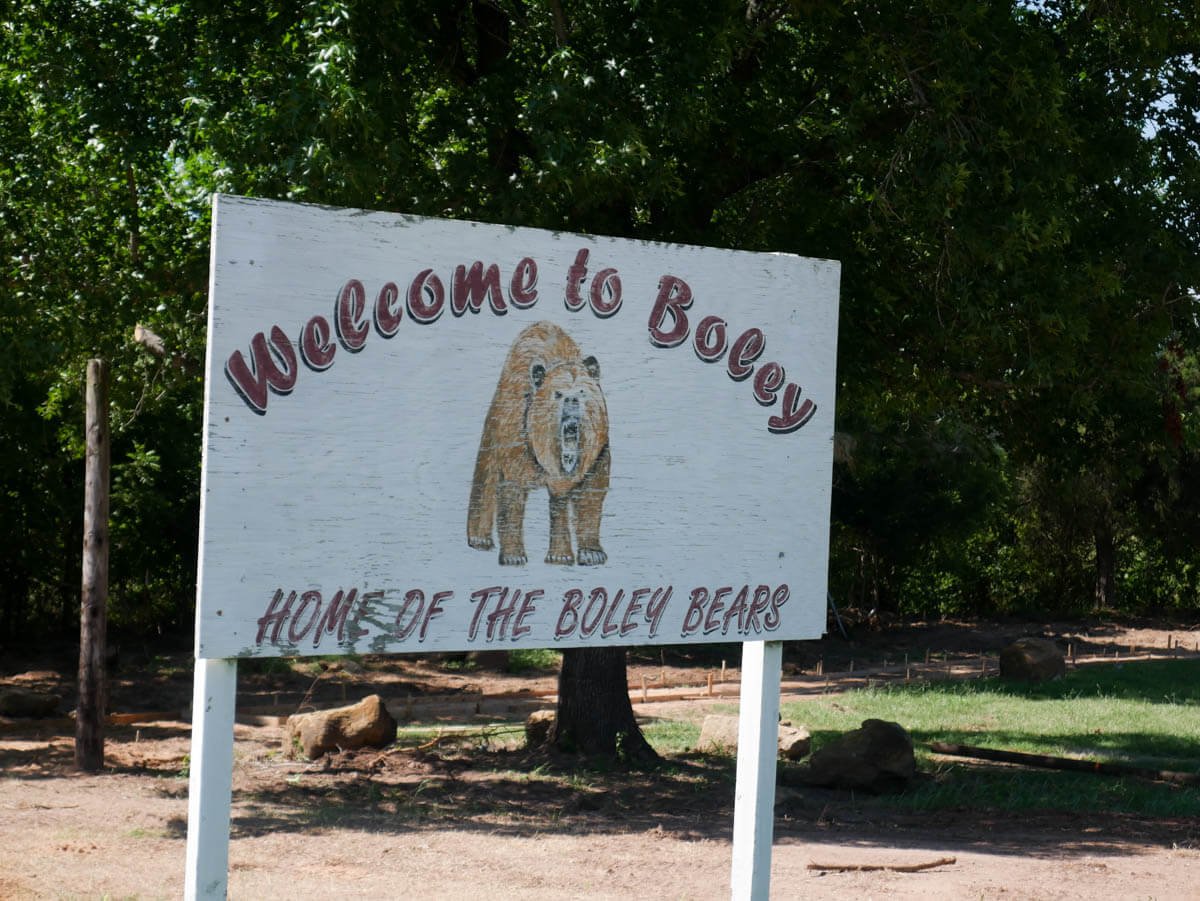

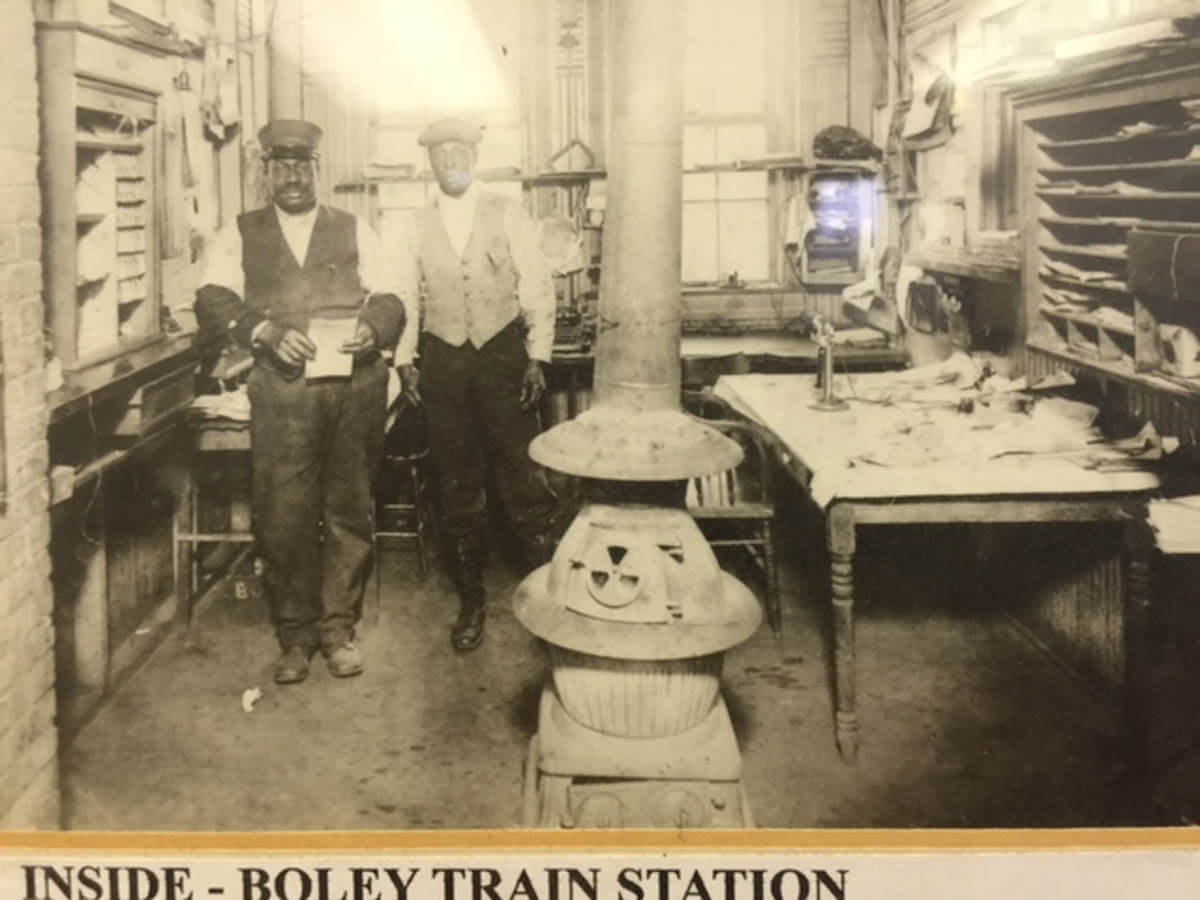

Boley, which was once one of the largest and most renowned, was founded in 1903 along the Ft. Smith and Western Railway. The town prospered after Lake Moore, vice president of the railroad, wanted to establish a depot there because he believed residents were capable of governing themselves, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

“It established itself as a self-governing town — by blacks, for blacks — and boasted at one point over 5,000 citizens,” Head said of Boley. “They had everything that Chicago or any other burgeoning town had.”

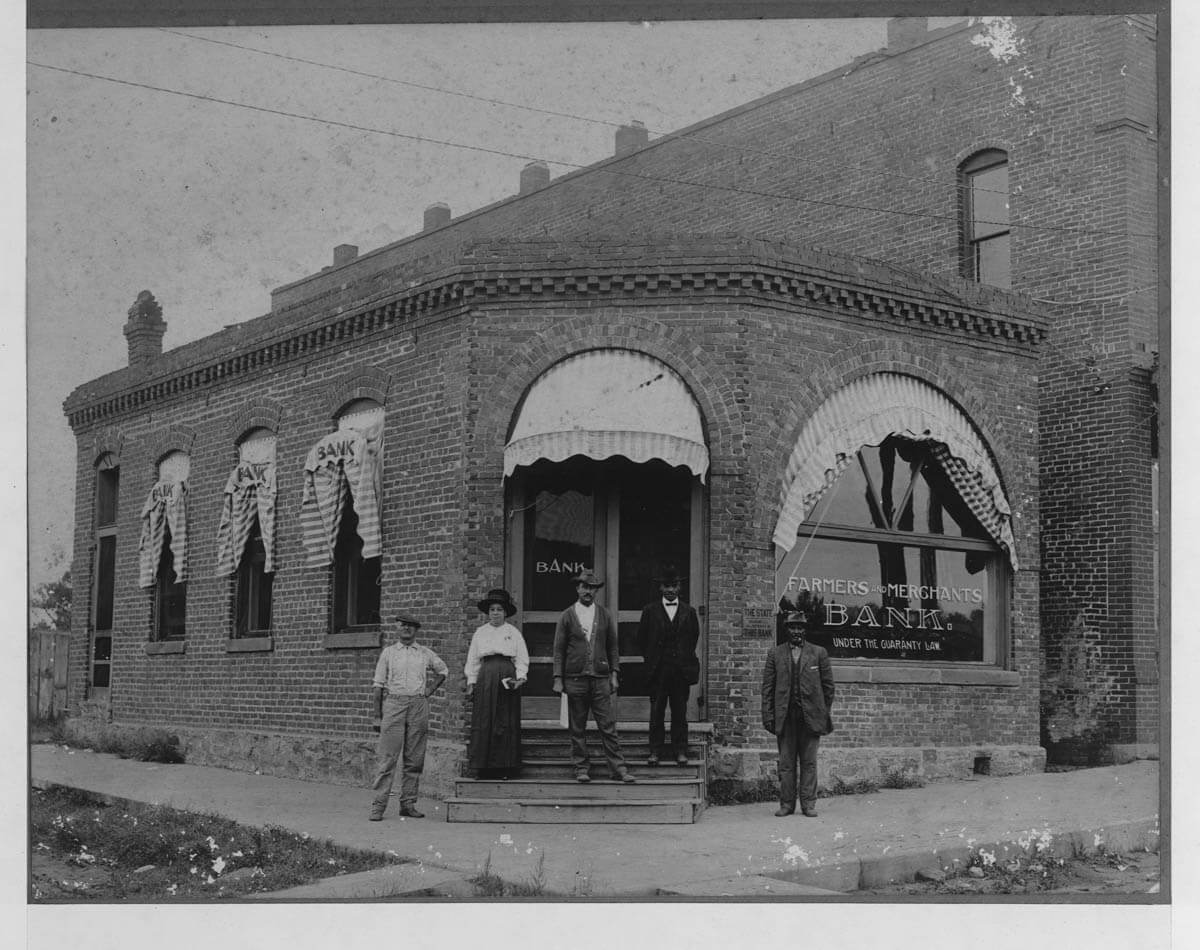

Boley had the first black-owned bank to receive a national charter, giving it the ability to operate on the same level as white banks. Telephone and electric companies were founded as well as a steam plant, Head said.

Famous African American educator Booker T. Washington visited Boley on occasions and called it “the most enterprising and in many ways the most interesting Negro town in the United States,” according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Langston a haven ‘from mob law’

The most modernly prominent of Oklahoma’s original all-black towns is Langston, home to Langston University, a historically black university.

Today, the undergraduate population of Langston University is roughly the same as the population of Langston the town, according to former Mayor Alicia Sumlin. With a total population of roughly 3,400 people, Langston stands as the largest of Oklahoma’s remaining all-black towns.

Langston attracted 251 settlers the first year it was founded. Several businesses sprouted early in the town, including a newspaper called the Langston City Herald, which was edited by the founder of the town, Edward P. McCabe.

“Here the negro can rest from mob law, and here he can be secure from every ill of the Southern policies,” McCabe wrote, according to the magazine.

Clearview known for its baseball team

Founded in 1903, Clearview sat along the same railroad as Boley to its southeast, said Shirley Nero, a town resident and historian. Early on, Clearview built a brick school and supported two churches. By 1904, a two-story hotel was constructed along with a print shop. To this day, Clearview still hosts a rodeo. Boley also holds a rodeo annually over Memorial Day weekend.

In its prime, Clearview attracted white people to watch the town’s baseball teams, which Nero said were among “the best in the country.”

“They would have games every summer just from all over the county and surrounding counties,” Nero said. “[White people] didn’t want to come down in town, but the teams were so good and so popular that they would come up here and sit on the railroad track instead of sitting on the bleachers.”

However, Clearview only reached a peak population of 618. By the late 1930s, the population went down to 420, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Today, the population of the town is 48, Nero said.

Dwindling populations

During the Great Depression and Dust Bowl of the 1920s and 30s, populations in Oklahoma’s all-black towns began to shrink as people moved elsewhere to find jobs.

In 1910, Rentiesville in McIntosh County had more than 400 residents. Famed historian John Hope Franklin was born in Rentiesville in 1915. The town’s population fell below 200 by the 1930 census, and the number is closer to 100 now. The annual Rentiesville Blues Festival has brought the town modern notoriety, though its founder D.C. Minner died in 2008.

Head said each of the towns lost their public schools owing to a law that removed schools with a low population. That left the children of the towns to be bussed to different towns for school and caused a greater decrease in numbers.

“When you affect your young people even when there are people who are very dedicated to the town, they will try to stay for a year, year and a half. They will watch their youngsters be bussed to the next town,” Head said. “So after about a year, those parents will say ‘You know, we love Langston, we love Summit, we love Redbird, we love Taft, but we are going to have to move.'”

The populations of the towns rarely recovered, and many lost resources. Many remaining residents of Clearview go without electricity and running water, Nero said.

She said residents used to use cisterns to hold their water, but the community decided it was not a safe way to store water and began digging wells.

“People would put tubs under the spouts of the gym and collect water when it rains,” Nero said.

Many of the buildings in Clearview have been damaged or destroyed by fire. One business remains — a clothing store — and there used to be only one working phone. But the people who live there love their town, Nero said.

By World War II, Boley saw its population shrink to about 700 people. However, the population has climbed back to about 1,100 people, a sign some view as a promise of new beginnings.

Looking for lasting support

Jessilyn Head and her husband, Andre, are working together through their Coltrane Group to revitalize the black towns in Oklahoma.

About five times a year, the pair hosts an all-black towns tour to highlight the history that African Americans have in Oklahoma.

“With the collective knowledge and perhaps investment in these towns by some of us or a collective of us — whatever it takes — we can ensure that their survival is exactly that,” Jessilyn Head said. “But it is also a return to a more successful days of their history that they reflect.”

The Heads hope that showing history to people and helping explain where they came from will encourage others to help.

“You will find black folk all over this country who got their start, their roots were established in these black towns,” she said. “We want them to remember that and to help contribute.”

One major effort from the group now is preserving the Farmers and Merchants Bank building in Boley. Jessilyn Head said the bank has been closed for nearly 25 years.

She said a grant of $24,000 was awarded to the group from the National Parks Service to start the initial steps, but they hope to find more funding for the renovation.

Eventually, a reenactment of the infamous attempted robbery of the bank by Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd and his gang in 1932 will be planned. Jessilyn Head said the original robbery “made the Farmers and Merchants Bank have national notoriety.”

Another plan for the group is preserving the home of famous black educator and poet Melvin B. Tolson, who was played by Denzel Washington in the film The Great Debaters. (Tolson is also the namesake of a library in Langston.)

“The fact that [Tolson] lived in that town for years, we are thinking that his home ought to be preserved and can be made into a lovely museum as an adjunct to the library itself,” Jessilyn Head said.

Andre Head said the biggest challenge for the group is finding volunteers to help with research and gathering resources to make their plans possible.

“We know that we can’t continue to do it ourselves,” Andre Head said.

The Coltrane Group do not have a website yet, but Andre Head said one will be created and showcased at their next banquet hosted in the fall.