When I began my counseling career, in 2005, our country was still recovering from the collective trauma of 9/11 and coping with the war that ensued. While few of my clients lost loved ones in those events, most reported experiencing a newfound general sense of anxiety and existential dread. As is often the case with such stressors, some self-medicated with drugs and alcohol, but many more turned to the relatively new platforms of 24-hour cable news and the internet. Information had become the new opiate of the masses.

Fifteen years later, we have grown accustomed to the never-ending news cycle, which has become even more omnipresent. We refresh our Twitter feeds while listening to podcasts, scroll through Facebook while streaming Netflix, and browse Instagram while Alexa reads us the headlines. We move mindlessly between multiple inboxes, now full of both end-of-season sales announcements and companies’ COVID-19 response plans. The sheer volume and variety of the information we’re currently taking in about the coronavirus bespeaks truths no one dares acknowledge: We were not prepared for this, and no one knows what to do.

This is a time of deep uncertainty, and it doesn’t help that many people’s daily routines have been upended, or that, because of the need for social distancing, we’re more isolated than usual. Many will experience fear, anxiety and depression. In the weeks and months to come, as our lives reorient around slowing the spread of COVID-19, it’s going to be particularly important to maintain an awareness of mental-health risks as well. I’d like to offer a few things to think about if you find yourself struggling.

You are not alone

Nothing in our lifetimes has prepared us for a global public health crisis of this magnitude or the economic uncertainty it brings. While that may seem scary at first, it also means that we’re all in this together and that no one should be expected to magically know how to cope with the situation. In short: It’s OK to not be OK.

As with any stressful situation, there is no “correct” way to respond. Our individual responses can be healthy or unhealthy, and they often oscillate between the two. The key is to maintain mindfulness — to practice being intentionally aware of ourselves, our feelings and our actions — and then to use that self-awareness to move toward healthier responses.

Boundaries are key

Most people are aware of the importance of setting boundaries in the context of interpersonal relationships, and those same principles can (and should) be applied to other aspects of our daily lives. This is particularly important as we adjust to the “new normal” of social distancing and working from home or, for many, unemployment. At times like this, when nearly everything in life feels out of control, one of the most helpful, healing and healthy actions we can take is to set limits on how we spend our time, energy and attention. These are scarce resources that should be allocated in a way that balances your needs while keeping you sane.

A great exercise to help you establish healthy boundaries is to do a quick assessment of everything that goes in and comes out of your body. Inputs can range from how much coffee and alcohol you drink to how much time you dedicate to news, social media or conversations with your friends. Outputs could be your physical activity level, your feelings or even the tone of your voice (both in person and online).

Once you’ve made your lists, look for relationships between inputs and outputs. Is there a correlation between the amount of coffee you consume and how much you sleep? Are you spending hours scrolling through Facebook but no time reading to your kids? Do you feel happier on days when you go outside for a walk? Then consider where you want to be for each category you wrote down and make plans for how you’re going to achieve it. How can you drink more water? Can you schedule a video call with a friend and put it on your calendar as if it were a work meeting? Is it better for you to write in a journal in the morning or the evening? Do you need someone to help hold you accountable to these things? What’s one thing you could do each morning to make your day just 1 percent better?

It’s OK to ask for help

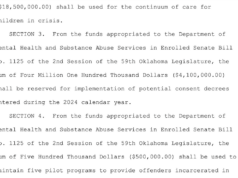

Perhaps the one unexpectedly positive outcome of this pandemic is that accessing resources from home has become easier in many ways. Telehealth services — including mental health and substance abuse counseling — has been made much more accessible. If you’ve ever considered talking to a counselor, now is a great time. You can find many listed on PsychologyToday.com or by simply searching the web for therapists in your area. State-operated mental-health centers are open as well. The Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services has released a guide that includes mental-health recommendations and resources related to the COVID-19 epidemic.

Another great resource hub is Heartline, which is accessible online or by calling 211 or texting your ZIP code to 898-211. If you are contemplating suicide or self-harm, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.