Seaboard Foods CEO Duke Sand sent a letter to Secretary of Agriculture Blayne Arthur on Monday announcing his company’s intention to begin site-wide COVID-19 testing at its Guymon pork-packing plant.

“The goal of our testing program is to provide employees the opportunity to determine their COVID-19 status, so they can better protect themselves, their families, co-workers, and friends,” the letter said. “It will also help us understand how we as a community have been affected by the global pandemic, and the next steps we need to take together to slow the spread.”

This move comes as Guymon, thanks to an outbreak at the Seaboard plant in particular, has become Oklahoma’s most severe COVID-19 hot spot.

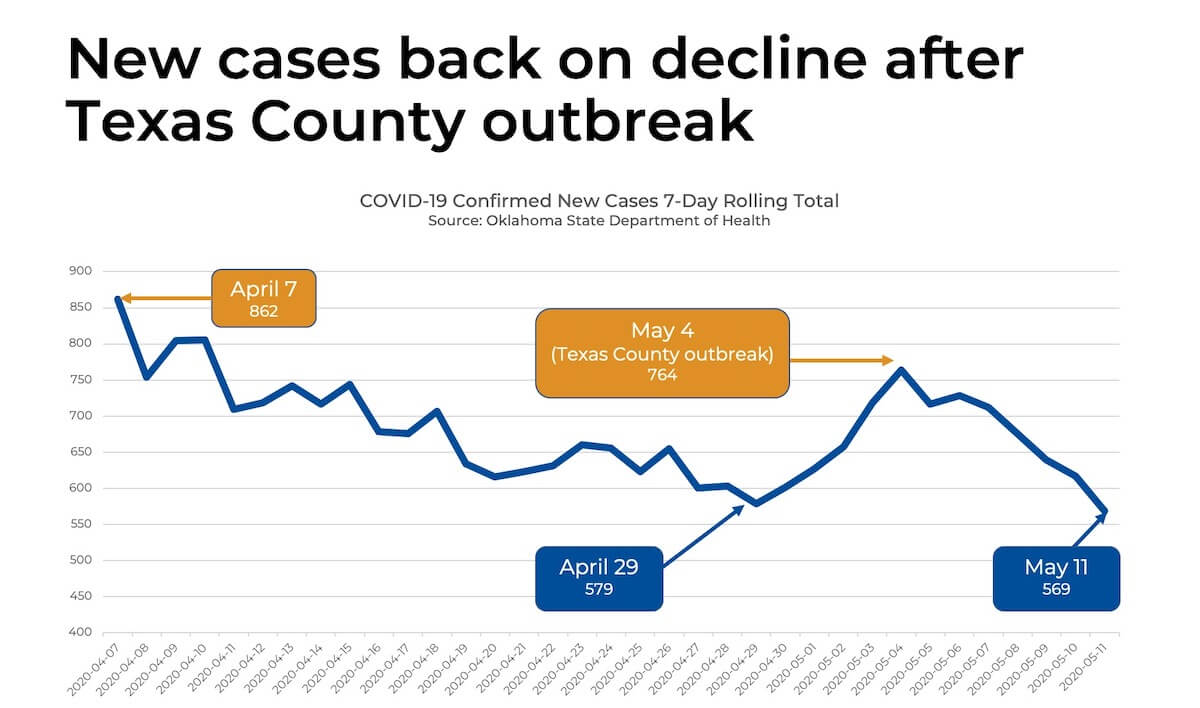

Texas County, where Guymon serves as the county seat, is the state’s 40th most populous county, with roughly 20,000 residents. But as of Monday it ranked fourth in the number of COVID-19 infections with 403 confirmed cases, coming in just behind the much larger Oklahoma, Tulsa and Cleveland counties.

Texas County has by far the highest rate of known infection in Oklahoma, with around 20 cases per 1,000 people. For comparison, the statewide ratio is just over one per 1,000.

The county has struggled to administer adequate numbers of tests even as Guymon, its main population center, has moved ahead with phase one of Gov. Kevin Stitt’s plan to re-open the state’s businesses.

It also faces the question of how to control the spread of the virus among employees at the Seaboard pork-packing plant, which has been deemed an essential business despite being an epicenter of outbreak.

Infections climb at the Seaboard plant

Seaboard workers make up the great majority of Texas County COVID-19 cases. The pork-packing plant employs about 2,700 people, and Sand’s letter said 206 workers have had confirmed cases, 90 of which are active, though not all infected employees live in Texas County.

Meat and poultry processing facilities have seen extremely high rates of infection nationwide. Employees in these assembly-line-style plants usually work at close quarters, and researchers believe cool temperatures and air-circulation patterns in the facilities contribute to the spread of the virus.

In a May 7 interview, Seaboard spokesperson David Eaheart said the company had implemented preventive measures, such as requiring face masks, staggering shifts, checking temperatures and installing barriers in some areas of the plant. He said employees are encouraged to stay home if they feel sick and are given up to two weeks paid leave if they or someone they live with are quarantined for COVID-19 symptoms.

Despite these measures, the plant’s number of infections has continued to climb. Eaheart said production has slowed because many employees are out sick or afraid of coming to work, but the goal is to keep the facility running.

Asked if Seaboard would consider purposely shutting down the plant or severely curtailing its production, Eaheart left options open.

“I think anything is possible at this point,” he said, noting that no infection threshold has been set. “There are a lot of variable factors.”

Sand’s letter to Arthur said Seaboard is working with the Oklahoma State Department of Health to bring COVID-19 test kits to the plant. Comprehensive is expected to start today.

“We know from watching testing efforts in other areas of the country that when more tests are conducted, more positive test results come in,” Sand wrote. “We are prepared for that and believe that broad employee testing is the right thing to do for the well-being of our employees and community.”

In a press conference on Monday, Arthur announced that Deputy Commissioner of Health Keith Reed was in Guymon to help coordinate tracing efforts and testing, which she believed would be completed by the end of the week.

“We certainly want to focus on the health and safety of the employees there at that processing facility,” Arthur said.

Trump order instructs plants to stay open

At the end of April, President Donald Trump issued an executive order under the Defense Production Act designating meat-packing facilities as “critical infrastructure” that need to stay open through the pandemic.

The order came with an announcement by the U.S. Department of Labor and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration that if a meat-processing company is sued for employees being exposed to COVID-19, the agencies would “consider a request to participate in that litigation” to support the company if it was following safety guidelines. The agencies said they would also consider supporting workers in litigation against companies that don’t follow guidelines.

Despite preventive measures, it can be difficult to adequately protect employees in meat-packing facilities.

“By the very nature of how our processing facilities are constructed, it’s very difficult to line up social distancing,” said Roy Lee Lindsey, executive director of the Oklahoma Pork Council. “Because they weren’t built that way. They were built for folks to stand side by side and work side by side, and that creates challenges.”

Likewise, shutting down a meat-processing plant is more complicated than shutting down most other businesses. Crucially, there is the question of what to do with all the animals. Slowed production quickly means millions of excess animals, which have to be euthanized. That’s a “horrible decision” for producers to have to make, Lindsey said.

He also emphasized that slowed or stopped production can have an impact on consumers.

“If we can’t run the plants at capacity,” he said, “then we run the risk of running low on product at the grocery store.”

At Monday’s press conference, Arthur echoed that concern.

“Those animals are fed specifically for a certain timeline,” she said.

Arthur said the Seaboard plant is operating at 60 percent capacity and that the Department of Agriculture had “approved excess capacity to hold some of those animals” to deal with the overflow.

She added that the state is exploring the possibility of re-opening meat-processing plants that have closed in recent years to help deal with the excess animals and donating some meat to local food banks.

‘Woefully’ inadequate testing at start of outbreak

As dire as the numbers are in Texas County, the reality of the situation might be even worse than data indicate.

In a widely shared Facebook post May 1, Guymon physician Dr. Martin Bautista wrote about seeing extremely high rates of positive COVID-19 tests.

“Last Thursday,” he wrote, “I sent 7 patients to the hospital and 7 tested positive.”

The numbers have remained concerning throughout May.

“That’s a very bad sign,” Bautista said in an interview last week, explaining that the high positive tests indicated that official numbers are a “gross underestimate” of the area’s actual cases.

“(A month ago), Texas County Health Department was testing up to 18 patients a day. That has since gone up to 36,” Bautista said on May 4. “But that is woefully, woefully, woefully [inadequate]. I mean, it wouldn’t even scratch the surface.”

NonDoc was unable to contact the director of the Texas County Health Department before publication, but recent posts on the department’s Facebook page said 28 people had been tested on May 8, with another 48 on May 7 and 38 on May 6.

According to Bautista, the clinic he operates with three other physicians initially struggled to obtain more than a handful of tests. He said the situation improved last week after his Facebook post when OSDH sent him 150 tests.

Still, those tests are mostly reserved for symptomatic patients. A large number of people who carry the virus don’t show any symptoms.

“From a public health perspective,” he explained, “you need to start treating asymptomatic individuals with known contact with COVID-infected patients.”

With limited testing, it’s not possible to know the true scale of the problem, he said.

“If we’re going to try to control this epidemic, let’s put in everything that we have and find out,” he said. “But right now, we’re blind.”

Guymon opens along with the rest of the state

Guymon Mayor Sean Livengood said last week that his primary priority is education of the public.

“We’re telling people to practice social distancing, to not gather in groups,” he said. The Guymon City Council is also meeting weekly to evaluate the unfolding situation.

The City of Guymon began allowing businesses to re-open at the beginning of May, in accordance with phase one of Stitt’s plan, which was based on downward trends in COVID-19 numbers.

“At the time when we made that decision, the numbers weren’t growing,” Livengood said. “So we decided to follow the guidelines of the governor.”

He said he wasn’t sure yet if the city would consider rolling back the openings if numbers continue to worsen.

“I can’t answer that at this point,” he said. “We’re using the data to guide us.”

‘I thought we were safe’

Guymon sits about four hours northwest of Oklahoma City, where the pandemic first hit home March 11. The arrival of COVID-19 in the panhandle weeks later took many Texas County residents by surprise.

“I think a big feeling was that we’re so far out that it’s never going to get to us,” said Teri Mora, a community advocate who works with Guymon’s large Hispanic community.

She pointed to an article Reuters published March 28, before the coronavirus had arrived in the panhandle, calling Guymon “an island of near normality in a pandemic.” The city had its first case that very same day.

Mora said she personally wasn’t shocked when Guymon’s COVID-19 numbers exploded, considering the number of people who work in meat packing and what she called a “cavalier attitude” about the pandemic.

“It was like I could see it happening in slow motion,” she said.

Sen. Casey Murdock (R-Felt) said last week that in the early days of the pandemic he had not anticipated it would come all the way to the panhandle. Then, a member of the State Senate staff tested positive on March 17.

“I thought we were safe,” he said.

Since, Murdock has been trying to educate his constituents, but it has been an uphill battle.

“I‘m still trying to convince people this is real and we need to be careful,” he said. “My mother being one of them. She’s 84 years old. She went through the (Great) Depression, the Dust Bowl, World War II, and you’re not going to tell her what to do. She can do whatever she wants to do, and she’s dang sure not going to let me — her son — tell her whether she can go to town or not.”

Murdock’s mother lives about a mile and a half from him, closer to New Mexico and Texas than Boise City, Oklahoma.

“She goes to town every day,” Murdock said. “I called her up one day and said she’s grounded. I told her, ‘Mom you cannot go to town.’ But no, she’s got to go. She’s working on quilts.”

Murdock praised the community leadership of Bautista, who said he worries people have the incorrect perception that the spread of the virus is limited to the largely immigrant communities that work at the Seaboard plant.

“For us to think this is happening to people who don’t look like us, it’s not true. It’s a silent killer that does not discriminate,” he said. “There isn’t a wall that separates these largely immigrant employees of the packing plant from the rest of the United States. And it will eventually affect everybody.”