Once upon a time, when Oklahoma was full of Democrats and Socialists, the state had a governor who practiced social distancing without anyone telling him it was a good idea. Unfortunately, as Oklahoma State University appears to have learned, that didn’t mean he was a good person.

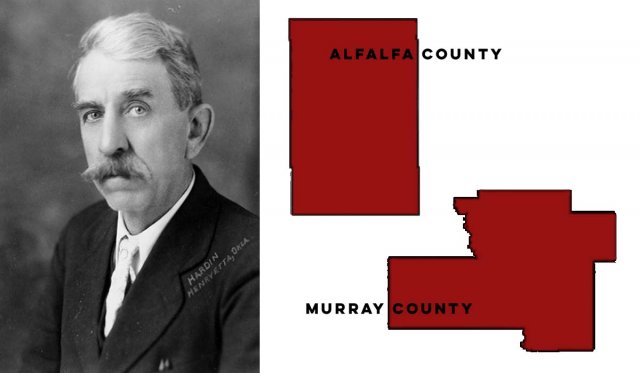

The governor was William Henry David Murray (1869-1956), better known as “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, owing to his penchant for touting alfalfa as a crop farmers should embrace.

Murray was born in Texas — Toadsuck, Texas, to be precise — and failed at any number of things before moving north and marrying into the Chickasaw Nation. He became involved in politics and, among other things, was elected president of the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention. He opened proceedings by having the delegates join hands and sing Nearer My God To Thee.

After statehood, he won some elections and lost some elections. He became the Oklahoma Legislature’s first speaker of the House, and he was a congressman in Washington D.C. for two terms before returning to Oklahoma and losing an election for governor. In the 1920s, he tried starting an agricultural colony in Bolivia. The effort, not surprisingly, failed.

Murray something of a clown

Back home in Oklahoma, Alfalfa Bill Murray ran for and served as governor from 1931 to 1935, with time out to run for president in 1932. Unhappily for him, the Democratic Party decided its nominee would be Franklin D. Roosevelt, a man Murray could not abide. Murray claimed that Roosevelt suffered not from polio but from syphilis, which had eaten its way to his brain and was the real reason he could not walk. It was a new low in American politics.

The stories about Murray are plentiful. Once, when he was running for office and campaigning in southern Oklahoma, the hall available for his speech was not large enough to accommodate the crowd. Murray sent for someone to go to the livery stable and bring up a wagon. He would stand in the wagon bed and make his speech in the street so that everyone could hear.

As it happened, the only thing available was the town’s “honey wagon,” a large barrel on wheels used to carry the contents of outdoor privies to the nearest creek for dumping. It was fly-specked, stained and odiferous, but Murray was not hesitant. He climbed up in the thing and said, “This is the first time I’ve made a Democratic speech from a Republican platform.”

As governor, Murray began acting more and more oddly, attracting national attention as something of a clown — saying and doing things that warranted coverage by magazines everywhere. His antics made people in other parts of the country think Oklahoma was governed by hicks and dummies. In his office, for example, Murray chained visitors’ chairs to radiators so that no one could slide closer to him and attempt an assassination. Social distancing, see?

After he left office, all sorts of stories circulated. He retired to his farm near Tishomingo, and no less a journalist than Ernie Pyle visited to see if Murray really had hired the village idiot to stand by the front gate and scare people away. Other rumors involved Murray having cut a hole in the floor of his house for better ventilation. Pyle had heard Murray spoke Choctaw with his pigs, but he never found evidence.

Word about Murray gets around

Murray was, of course, a terrible bigot. He had used a racial slur to describe African Americans in his 1931 inaugural address, so he went to the all-black town of Boley and crudely tried to explain what he meant: that black Oklahomans, poor whites and Native Americans would finally have a governor who worked for them, too.

He wrote and published his own books, one of which was entitled The Negro’s Place in the Call of Race. It “discussed the subject from Bible account (sic) of the ‘First Segregation’ by Noah, on account of the ‘Curse’ when he sent them to Equatorial Africa (…), the effect on intelligence and brain weight” and racist arguments about criminality, with occasional asides about Communists and Jews. The little book sold for a dollar and was popular among some.

Murray wrote a three-volume autobiography, which he bundled and sold door-to-door. The thing was full of every embarrassing statement and tale one could imagine, and for years the Murray family went around stealing copies from libraries for that reason.

Reading Murray’s books is enough to make one wish he had continued social distancing in Bolivia and had not come back to become what textbooks call “Oklahoma’s most colorful governor.”

The announcement that the OSU A&M Board of Regents will be voting Friday to remove his name from a building suggests that the word about Murray is getting around at long last. One can only hope the State Regents for Higher Education realize Murray State College also is named for the bigoted buffoon, though the Murray moniker is specified in state statute. And then what are we to do about Alfalfa County, Murray County and Lake Murray, which are all named after our infamous ignoramus?

Oh, the questions that must be asked when we finally reckon with our history.

(Update: This article was updated at 9 a.m. Thursday, June 18, to include additional information about state statute.)