Say you are a single adult with one child working a minimum-wage job in Oklahoma. You make $7.25 an hour and have no health benefits through your employer. Then say you work that job 40 hours a week every week of the year. At the end of the year, you will have made $15,080.

Your income is far too high to qualify for Medicaid in Oklahoma, and even if you manage to qualify for health insurance premium assistance payments through the federal marketplace, your private plan deductibles are likely to total at least one-third of your annual income. Plus, what if you did not have a child and were just an adult working a low-wage job?

Many people in these positions are left without affordable insurance options. Thus, they remain uninsured, often avoid preventative care and are commonly saddled with a sudden debt when they do get sick.

According to the latest numbers released by the U.S. Census Bureau, Oklahoma had the second-highest uninsured rate in the country in 2018, at 14.2 percent or 548,000 people — 3,000 more than the year before.

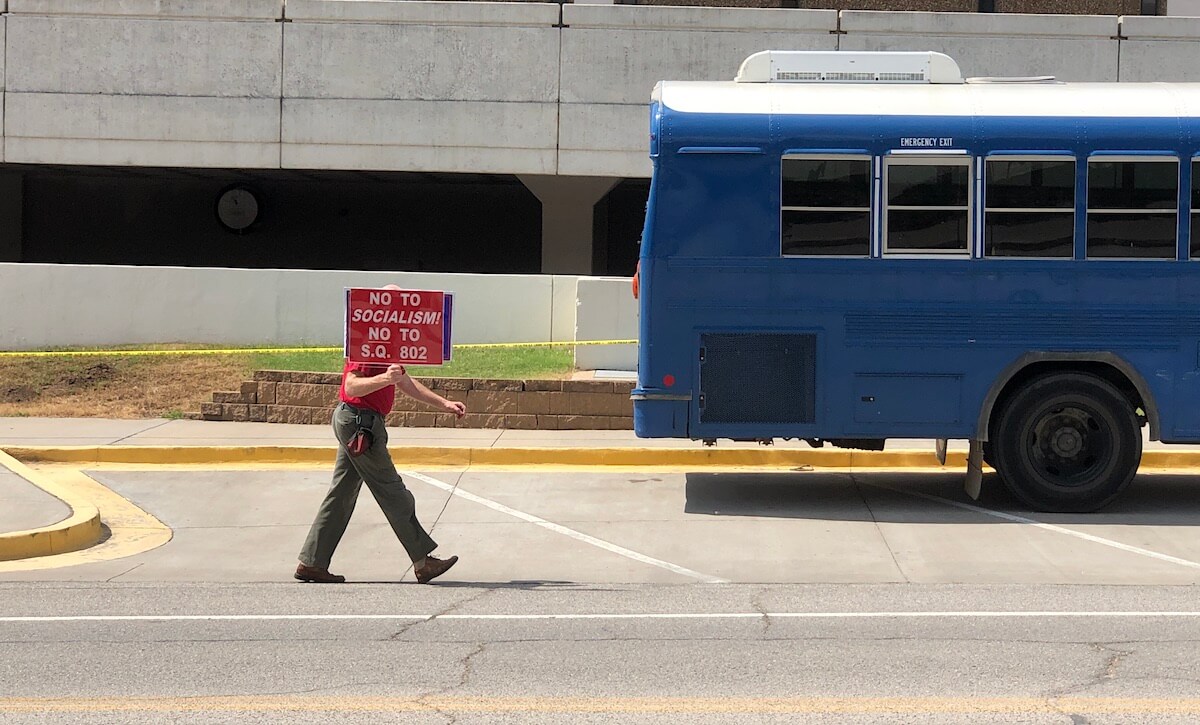

Oklahomans heading to the polls on June 30 will be asked to vote on one proposed solution: State Question 802, which would amend the Oklahoma Constitution to extend Medicaid health coverage to all adults under 65 who have an income of up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level.

Currently, adults without disabilities or dependent children can’t qualify for SoonerCare, as Medicaid is called in Oklahoma. An adult with one dependent child can’t make more than $7,596 annually (about 44 percent of the federal poverty level). For a family of four, the household income must be $11,532 or less.

If 802 passes, any adult making under approximately $17,000 will qualify. The income limit for a family of four will be just under $35,000. The income levels are designed to ensure coverage for those with incomes in the eligibility gap between Medicaid and the insurance marketplace. Approximately 111,000 Oklahomans fall into that gap.

Medicaid expansion was originally mandated by the Affordable Care Act, but a Supreme Court ruling in 2012 made it optional for states. Oklahoma is one of 14 states that have not undertaken a Medicaid expansion.

However, Oklahomans will be voting on the measure in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has upended the economy and the state budget while also drawing new attention to the country’s handling of health care crises.

Medicaid expansion and the fallout of COVID-19

Both supporters and opponents of SQ 802 see the fallout of the pandemic as reason to support their own position.

“I think people understand now more than ever that people need health care when they need it,” said Amber England, the campaign manager for Yes on 802.

Those opposed to the measure point to the economic effects of the pandemic.

“We just simply don’t have the budget for it, especially through COVID but even before that,” said Joey Magana, the state deputy for Americans For Prosperity, which has opposed the measure. “Putting that into the budget without either raising taxes or cutting other core services — we just don’t think it would be possible.”

When discussing costs, proponents of State Question 802 point out that 90 percent of the expansion would be funded by federal money.

“We need to bring this money home from Washington — over a billion dollars every year — to boost our economy and protect jobs,” England said.

To Magana, the differentiation between state and federal funds is beside the point.

“It’s all taxpayer money,” he said. “We kind of view it as the same.”

Weighing the financial cost of Medicaid

As of April, 821,803 Oklahomans were enrolled in Medicaid.

The Oklahoma Health Care Authority doesn’t have projections specifically for how SQ 802 would change enrollment.

However, OHCA numbers from May estimated approximately 215,000 new Medicaid enrollees under Gov. Kevin Stitt’s Medicaid expansion plan, costing the state $164,138,054. That number included additional 46,920 enrollees resulting from the recent increase in unemployment.

The Stitt plan, called SoonerCare 2.0, presented a competing version of Medicaid expansion under a Trump administration initiative that grants states flexibility to impose restrictions on coverage when expanding Medicaid.

Whereas 802 offers coverage across the board to those who meet income requirements, Stitt’s plan came with work requirements, copays and a per capita spending cap for those covered by the expansion.

The details of SoonerCare 2.0 were submitted for federal approval in April, and the program was set to go into effect on July 1. However, in May, Stitt vetoed SB 1046 that would have provided $134 million in funding for the program and subsequently withdrew his plan for July 1 expansion.

In his veto message for SB 1046, Stitt faulted the bill for not fully funding the program and also cited rising unemployment resulting from COVID-19 leading to higher eligibility numbers and higher costs for the program.

“When I announced SoonerCare 2.0, unemployment rates were at 3.2 percent,” he wrote. “Due to the current COVID-19 pandemic and uncertainty within energy markets and commodity prices, unemployment rates are predicted to be as high as 14 percent. This will not only increase the number of individuals currently enrolled in Medicaid, but will also increase the number of potential enrollees in the expanded population.”

On Tuesday morning, Stitt said in an appearance with Americans for Prosperity, a conservative group that has been one of the most outspoken opponents of the measure, that he would be voting against 802 as well.

OKC Mayor David Holt was asked his position on SQ 802 during a Tuesday press conference about COVID-19. Holt declined to say whether he supports or opposes the ballot measure, arguing that it’s outside of the responsibility of a mayor to address. He noted that metro hospitals and the Greater Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce were in favor.

Medicaid expansion and the future of rural hospitals

The uninsured rate is higher in small towns and rural areas than it is in metropolitan centers. This places a financial burden on rural health care facilities, many of which are already struggling to stay afloat.

Oklahoma has seen seven rural hospitals close in the past ten years — the third highest number in the country.

In general, states that have not expanded Medicaid have been hardest hit by rural hospital closures, though opponents of 802 point out that Medicaid expansion has not been enough to stave off closures entirely.

Doug Weaver is the CEO of Hillcrest Hospital in Pryor, a town of about 9,500 in northeastern Oklahoma. He said the uninsured make up between 8 and 10 percent of the patients his hospital sees, but that number is on the low end for small-town facilities.

When the hospital receives patients who lack insurance and can’t afford to pay themselves, the hospital ends up writing off the entire cost of care as a loss, Weaver said.

“It definitely affects you,” Weaver said. “You still have to give them care — we don’t deny their care — but we accept that.”

Weaver said that if SQ 802 passes, the expected economic benefit for the health care facilities in Pryor would be around $2 million, according to numbers from the Oklahoma Hospital Association, which supports the measure. Increased use of medical services would also lead to jobs in the sector, he said.

The Pryor hospital is in fairly good financial shape, largely because it has an outpatient surgery center, “which carries the load,” Weaver said. But many other facilities are much closer to the edge.

“Rural health care is a little bit different than urban cities,” Weaver said. “We definitely are the safety net hospitals, so people depend on us to be open, and Medicaid expansion is going to help us do that.”

In the homestretch

The Yes on SQ 802 campaign has been in the works for quite some time. The process to get it on the ballot officially began in April 2019, and the petition was submitted to the Secretary of State’s office with a record 299,731 valid signatures (well over the required 178,000) in October.

The Yes on 802 campaign has also built a wide base of support, gaining endorsements from the Oklahoma State Medical Association, the Oklahoma Policy Institute, the state’s Catholic bishops, the Greater Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce and others.

RELATED

State Chamber of Oklahoma board endorses SQ 802 by Tres Savage

“We have strong grassroots support all across the state,” England said. “We’re feeling as good as we can, but taking nothing for granted, and we’re going to campaign until the very last minute.”

Opponents of the measure don’t have the organizational structure of England’s campaign, but they are making a concerted push to defeat the measure as the election enters the homestretch.

On June 5, a political action committee called the Vote No on 802 Association registered with the Secretary of State’s office, with Americans for Prosperity state director John Tidwell listed as chairperson.

As of June 17, the PAC had spent more than $145,000 on mailers and online ads for the homestretch of the campaign, according to filings.

“We feel confident that if we get our message out there, it will resonate,” Magana said. “Oklahomans will come to understand the budget needs that we have.”

A poll of 500 likely voters conducted at the beginning of June by Amber Integrated showed the supporters of 802 with a comfortable 60 percent lead, with 23 percent opposed and 17 percent undecided.

If voters approve State Question 802, Medicaid expansion would go into effect in July 2021 for the start of state Fiscal Year 2022.