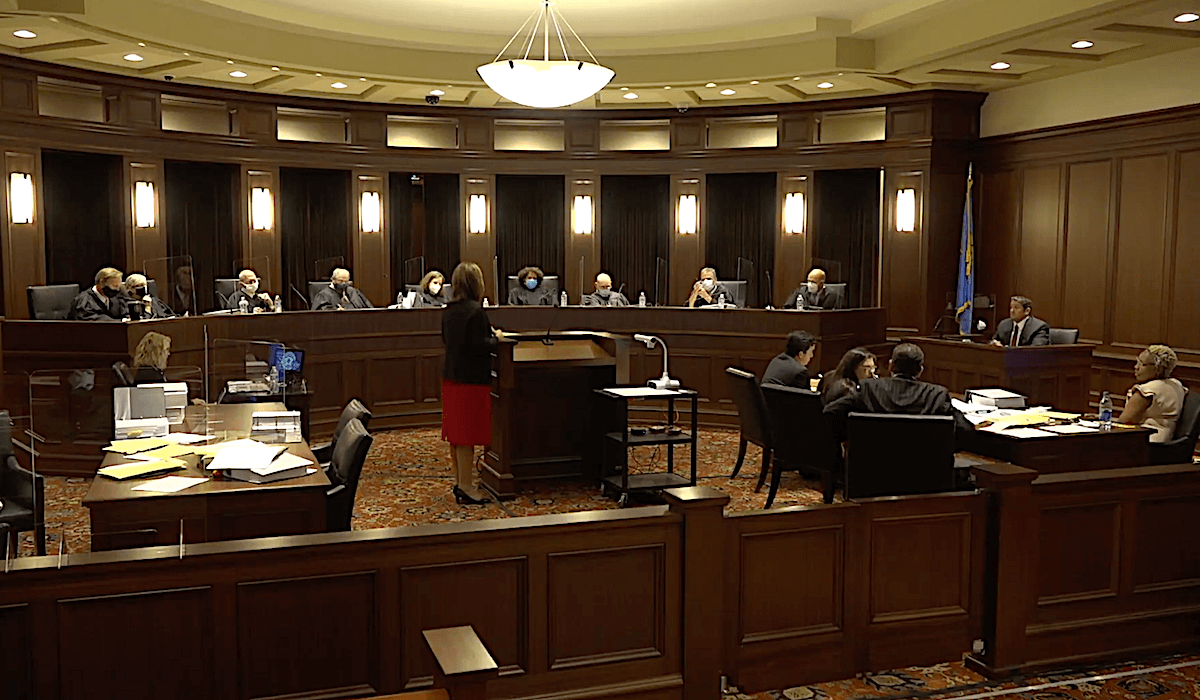

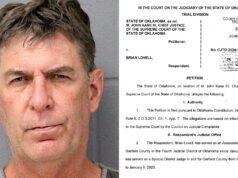

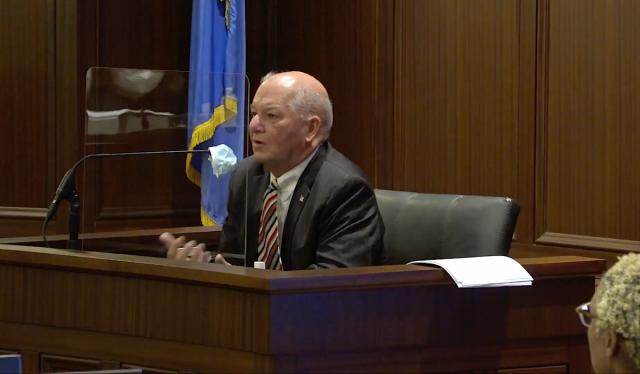

During his testimony on Tuesday in the second day of a trial before the state Court on the Judiciary that could result in a judge’s removal from the bench, Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater said he believes Judge Kendra Coleman violated the state code of ethics and denied that his office was out to get her.

Prater testified Tuesday that he had sought recusal of Coleman from all Oklahoma County District Court criminal cases in September because he found she had failed to provide campaign finance reports to the Oklahoma Ethics Commission that should have disclosed contributions from defense lawyers.

Coleman faces the unusual removal trial on charges that she failed to file campaign finance reports on time and violated a probation imposed by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in December owing to her treatment of lawyers and litigants.

The second day of the removal trial also saw presiding Oklahoma County District Judge Thomas Prince testify about private conversations he had with Judge Coleman before he reassigned her from the criminal docket. Prince said Coleman declared, “I knew you would not support me.”

At the time, Coleman was the only Black district judge assigned to criminal felony cases in Oklahoma County.

But most of Tuesday’s hearing was consumed by the testimony of Prater.

Prater admitted one of the items of “evidence” he obtained was an unsigned court document photographed in Coleman’s chambers by a court clerk employee and shared with the district attorney by another district judge without Coleman’s knowledge. The document presented in the trial Tuesday appeared to be a draft order denying Prater’s motion before it had been heard.

Prater said he confronted Coleman with the document because he believed it was direct evidence of what he called an unlawful act.

“I think she violated the code of ethics when she pre-determined her decision in the open hearing to recuse her of all criminal matters,” Prater said. “And I felt like it was violation of the code of ethics.”

Prater said he did not have a subpoena to get the document, but he defended his use of it during the recusal hearing to show Coleman’s bias against the district attorney in criminal cases.

“I didn’t need her permission,” he said. “It was direct evidence she had already made up her mind in the hearing before we even had it.”

Prater said District Judge Cindy Truong gave him what appeared to be a cell phone photograph of the document. Truong served as an assistant district attorney for 10 years before becoming a judge.

An appeal of Coleman’s refusal to recuse led to a referral of the allegations of bias to the Counsel on Judicial Complaints. Prater said he also filed a complaint over Coleman’s failure to file appropriate campaign finance reports, one of the charges that lead to this week’s trial before the seldom-used Court on the Judiciary.

Prater also said he was disturbed by Coleman’s treatment of his assistant district attorneys.

‘Demeaning and sarcastic’

The testimony on Tuesday by Prater centered on a manslaughter case against the owner of two pit bulls that fatally attacked an elderly woman in 2017. At a hearing to determine the admissibility of photographs of the victim’s mangled body, prosecutors testified on Monday that Coleman had been unduly aggressive toward them.

TRIAL DAY ONE

Unusual removal trial starts for Judge Kendra Coleman by Michael Duncan

Prater said he sat in on portions of that hearing in May 2019. Asked by acting prosecutor Tracy Schumacher to describe Coleman’s demeanor, he offered three assessments: “Pretty hateful”, ”demeaning and sarcastic” and “unprofessional.”

But on cross examination by Coleman’s lawyer, Joe White, Prater was unable to find examples of this behavior in a transcript of the hearing.

“A cold transcript is not going to indicate that,” Prater said.

Prater’s first Assistant District Attorney Jimmy Harmon also testified Tuesday that Coleman threatened him with contempt citation when he asked her to recuse from four or five specific cases after she refused the DA’s request for a “blanket” recusal from all criminal cases.

Audio recordings of several in-chambers conferences between Coleman and prosecutors over the recusal issue were played to the Court on the Judiciary trial panel Tuesday. The recordings show contentious exchanges between Coleman and Harmon with each accusing the other of being disrespectful.

Harmon argued that the state’s pending motion to recuse Coleman prevented her from considering any cases, but Coleman disagreed.

“She kept threatening to hold me in contempt,” Harmon said.

Although Prater said he had no issues with Coleman before the dog-mauling case, he said he had some concerns when she was elected because of some statements she made when campaigning for the office in 2018. He said Coleman had criticized the DA’s office for how Black defendants were treated.

‘This is not a threat’

The audio recording of a Sept. 3, 2019, meeting on the DA’s request that Coleman recuse from all criminal cases showed the most pointed exchange between prosecutors and the judge.

“You have shown no (legal) authority for your request. You’ve shown no indication of bias,” Coleman was heard telling Prater. “I can and will continue to be impartial.”

Prater responded by telling Coleman she had flagrantly violated state law in failing to file required campaign finance disclosures with the Oklahoma Ethics Commission for more than seven months.

“How is the state of Oklahoma ever going to be sure that you’re going to follow the law on anything, if you don’t feel like you want to?” Prater asked Coleman. He said he had checked that morning on the Ethics Commission website and was unable to find timely reports.

“You have not filed them?” he asked.

“I’m not answering your questions.” Coleman said.

Prater then told the judge he would be seeking her removal from the bench and was going to contact the Attorney General Office to bring a petition for her removal before the multi-county grand jury.

“You need to be aware of that, judge. This is not a threat,” Prater is heard saying.

Coleman replied, “You can do whatever. I’m not going — this is a recusal hearing.”

“Have you filed them?” Prater asked.

“We’re done here. Thank you so much,” Coleman said.

Campaign finance disclosure reports were introduced in the removal trial on Tuesday that showed Coleman had filed a report a week before that in-chambers hearing and another report was filed later in September.

‘You think this is all about race?’

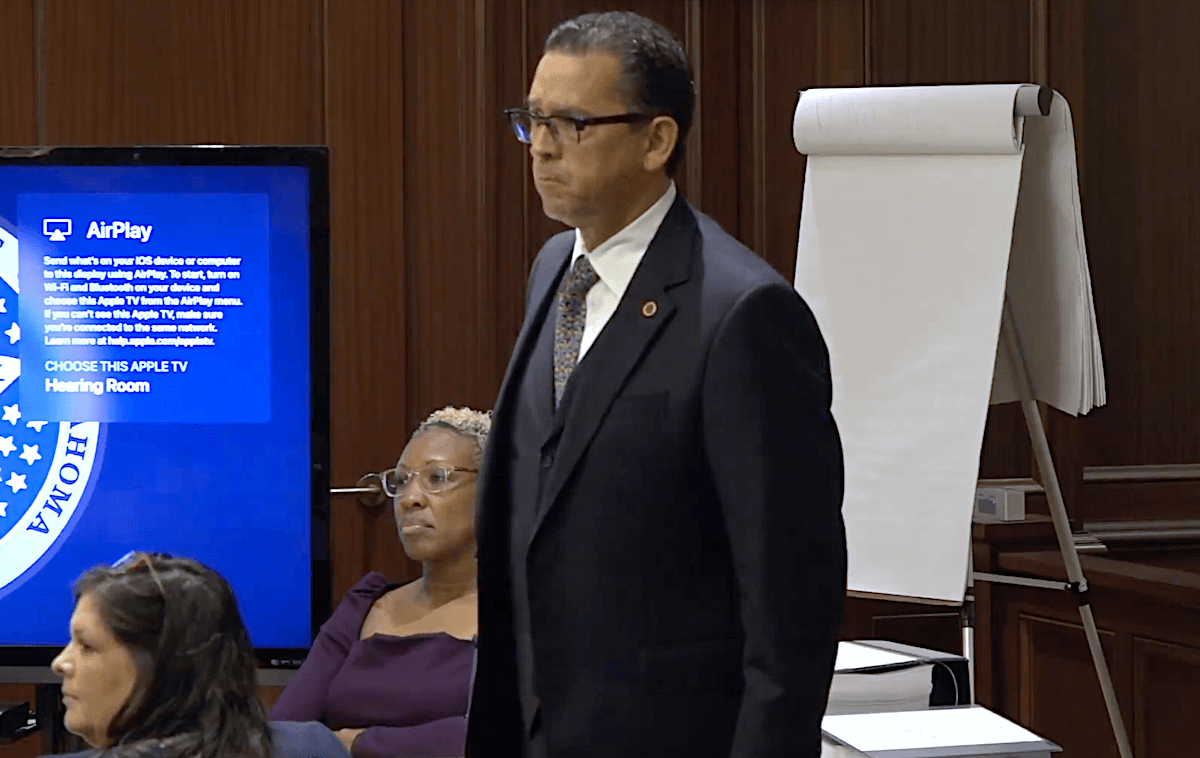

Late Tuesday afternoon, presiding Oklahoma County District Judge Thomas Prince testified that his role compelled him to remove Coleman from the criminal docket on a temporary basis until the issues about campaign finance reports and tax liens could be resolved.

Before then, he said he had counseled Coleman about her verbal treatment of lawyers, including public defenders, who had complained. He also suggested to her that her decision to place a courtroom visitor in jail for contempt of court after their cell phone rang during a hearing had been too harsh.

Prince said Coleman responded professionally when he talked to her about judges needing to treat everyone with respect.

But when Coleman’s campaign finance reporting problems surfaced and Prater was seeking her removal from all criminal cases, Prince said he had to take action wearing his court administrative hat as the presiding judge.

He testified that he met with Coleman and District Judge Cindy Truong, the vice-presiding judge, to discuss reassignment from the criminal docket.

“Judge Coleman said this is frivolous,” Prince said.

Prince said he told Coleman that news stories about the Ethics Commission filing problem had given Prater an avenue to seek her recusal.

“She said, ‘Well, shame on you and shame on him for thinking that,'” Prince recalled. “I said, ‘Well, Judge Coleman, the reports, this newspaper story looks pretty significant. This looks serious. If you haven’t filed your campaign reports since January — a report due in January and here it is seven, eight months later, that looks like circumstantial evidence of intent. And that’s serious.

“She said, ‘This is not a big deal. People are late in their campaign filings all the time, and I have the support of my community.’”

Prince said he had previously talked with Coleman about her use of the phrase “my community” and said that he disliked it, because judges are supposed to represent all of the county and not any one segment.

Coleman holds one of Oklahoma County’s 14 district judge seats and is elected from a particular subdivision of the county. Some other district judges are elected in countywide elections, but all serve the same function in the district court. Oklahoma County district judges have currently appointed 19 special judges as well.

Prince told the court his recollection of a conversation with Coleman: “She said, ‘Well, what do you think I mean when I say, ‘My community?’ I don’t know what I said, but I remember she in that context said, ‘You think I’m referring to Black people. Black voters.’ She used the word ‘Black.’ I said, ‘Predominantly your subdivision is from northeast Oklahoma County.’ She said, ‘Well I don’t see it that way, and there are all kinds of races in my subdivision.’ And I said, ‘Well, regardless of how you look at their race or ethnicity, we represent all of Oklahoma County.’”

Prince said Coleman was upset and accused him of treating her differently than others.

“She didn’t call me a name,” Prince said. “What she said to me was, ‘You’re treating me differently because I’m a — and I don’t know what she said — if she said woman or said African American — I don’t know what word she put at the end of that. I’ve tried to remember, but honestly I don’t. (…) But I know what I said in response. I said, ‘You think this is all about race?’ And I said it emotionally like that, ‘Do you think this is all about race?’ Her answer was, ‘I can’t answer for you.’”

Prince testified that Coleman did not use the words “racist” or “racism,” but he said he took what may have been accusations of discrimination seriously.

“She didn’t accuse me of racism or anyone else of racism,” Prince said. “What she said was, ‘You’re treating me differently.’ And I took it as race. I took it seriously. I said, ‘I have seen racism.’ Or words to that effect. ‘And you are being treated just the same as anybody else.’”

Prince said he waited until the next week before deciding to move Coleman from the criminal docket to handling guardianship and probate matters because he perceived Coleman’s comments may have been an accusation of racism.

“I thought it important to slow down,” he said. “Think about this. Am I treating her differently than I would treat anybody else?”