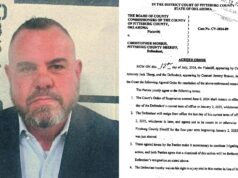

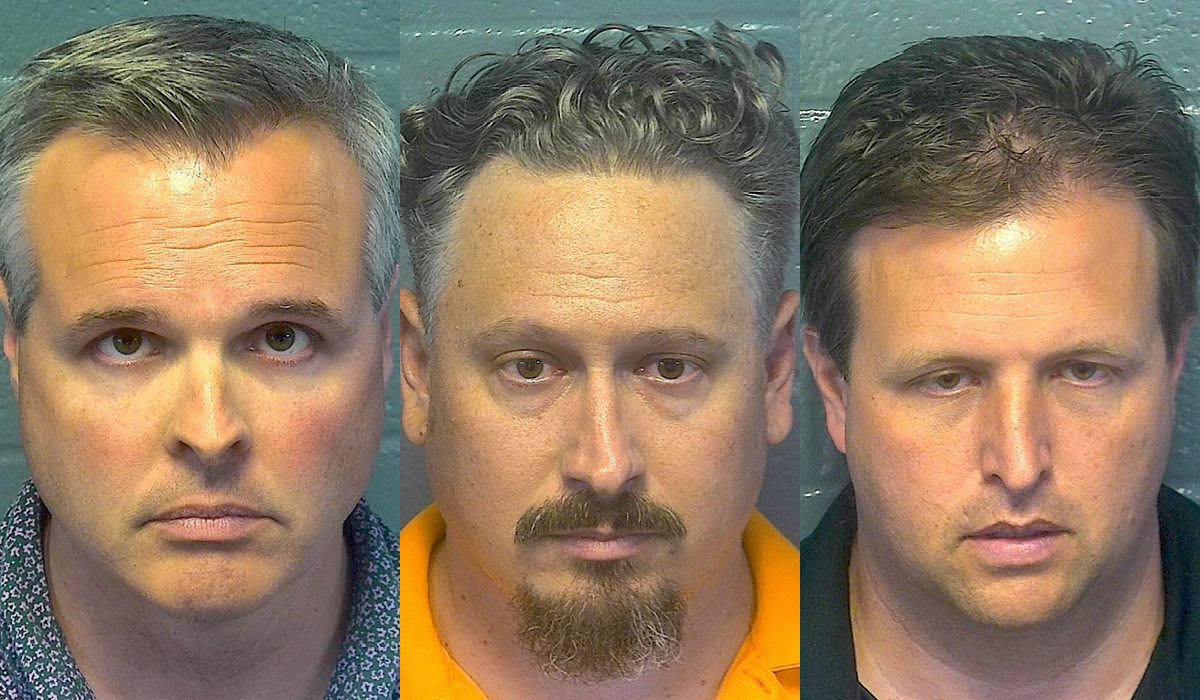

On a fifth grueling day of testimony in the preliminary hearing for the embezzlement case against Epic Charter Schools co-founders Ben Harris and David Chaney, former chief financial officer Josh Brock took the stand as part of a plea agreement and described how his former bosses attempted to shield their management company’s use of money from public scrutiny.

But even after more than 30 hours of questions and answers from eight witnesses this week — including painstaking cross examinations from the two defense attorneys — the high-profile hearing had not concluded when the Oklahoma County Courthouse prepared to close Friday.

As Judge Jason Glidewell attempted to set the matter for resumption Monday, defense attorneys Gary Wood and Joe White became aggravated. Wood said he has a jury trial starting Wednesday, and White said it would take him “two days” to cross-examine Brock, who still faces “an hour or two” of additional questions from Assistant Attorney General Jimmy Harmon.

RELATED

Epic embezzlement case: ‘Learning fund’ examined in preliminary hearing by Bennett Brinkman

Glidewell finally acquiesced and continued the hearing until May 7 and May 8, nearly two years after Harris, Chaney and Brock were charged with racketeering, embezzlement and money laundering for how they handled hundreds of millions of dollars in state funding sent to the Epic Charter Schools that Harris and Chaney founded.

The protracted proceedings and calendar calamity mean more than a month will pass between this week’s testimony from eight witnesses and Glidewell’s decision on whether enough evidence exists to bind Harris and Chaney over for trial.

Attorney General Gentner Drummond’s office declined to comment on the continuance, which comes as the latest delay in a hearing that was originally scheduled to occur more than a year ago.

‘How many certified employees were there in EYS?’

While testimony Wednesday and Thursday largely involved a massive state audit that accused Harris and Chaney of fiscal malfeasance, Brock testified most of the day Friday and said he had reached a plea agreement with prosecutors in exchange for his cooperation. Brock said the agreement includes restitution payments and a 15-year suspended sentence, during which he would be on probation. A suspended sentence constitutes a conviction.

Witnesses who testified this week:

• Lead OSBI investigator Mark Drummond;

• Former longtime Epic board chairman Doug Scott;

• Current Epic employee Chandler Winningham who works with the learning fund;

• Oklahoma State Department of Education state aid program director Renee McWaters;

• Epic deputy superintendent of finance Jeanise Wynn;

• Salesha Wilken, investigative audit manager in the State Auditor and Inspector’s office;

• Brenda Holt, director of forensic audits in the State Auditor and Inspector’s office; and

• Josh Brock, a defendant in the case and former chief financial officer of the school.

Brock had been involved with Epic’s online charter school almost since its beginning in 2011, holding various titles but essentially overseeing finances for the school and its contracted management organization — Epic Youth Services — that Harris and Chaney owned.

At issue in Harris and Chaney’s preliminary hearing has been the separation — or lack thereof — between the nonprofit Epic Charter Schools and the for-profit management company.

Harmon, who had watched his colleagues question the first seven witnesses of the week, handled the questioning of Brock and emphasized the relationship between the two organizations. Harmon attempted to show that both the school and EYS were essentially controlled by both Harris and Chaney and that the men used EYS to hide state money from auditors. Defense attorneys objected to Harmon’s form of questioning, but Harmon told Glidewell that the issues spoke directly to the defendants’ culpability.

“Your honor, the state’s evidence is that Mr. Harris and Mr. Chaney controlled the school — maybe not on paper but in actuality. And how did they do that? They picked the board members, they controlled the board members, they told them what to do,” Harmon said.

Under its contract, EYS received 10 percent of all Epic Charter Schools revenue to manage the pair of virtual schools, Epic Blended and Epic One on One.

Prosecutors contend that Harris and Chaney made millions in profits while faking invoice numbers to justify the 10 percent management fee and keep millions of dollars of state funds in their private company’s bank accounts.

To illustrate the point, Harmon displayed an invoice from EYS to the school for services the company performed that month. On the itemized invoice, EYS charged Epic for certified staff salaries and nutrition services, even though Epic, as a virtual school, did not provide nutritional services for its students.

The exchange illustrated the unusual arrangement:

Harmon: “These are line items to make up the 10 percent management fee?”

Brock: “That is correct.”

Harmon: “How many certified employees were there in EYS?”

Brock: “I recall having one employee.”

Harmon: “What did he do for EYS?”

Brock: “He did some security work as well as drive myself and other members of the team around.”

Harmon: “So do you believe it’s accurate to count his salary in the list of certified employees?”

Brock: “No I do not.”

Harmon: “It’s being charged as 10 percent, but you’re just trying to justify it with all these bogus numbers, is that correct?”

Brock: “We were trying to get back to that 10 percent, yes.”

Josh Brock testimony: Learning fund meant ‘for the benefit of students.’

Harmon spent much of the day talking with Brock about Epic Youth Services’ 10 percent management fee and the school’s controversial student learning fund, which was intended to provide access to things like tutoring, technology and extra-curricular activity items.

Brock testified that, in Epic’s early years once EYS took over the learning fund, the three men developed a mentality toward that money. At Harris’ suggestion, Brock said, they decided they could use “leftover” learning fund money for their personal retirements or other savings.

“As you sit here today, do you think that was your money to spend?” Harmon asked Brock.

“No, I do not,” Brock replied

Harmon continued: “Do you think that was Mr. Harris’ money to spend?”

“No, I do not,” Brock said.

Harmon asked the same about Chaney and received the same answer.

“Whose was it to spend?” Harmon asked Brock.

Brock replied: “It was for the benefit of the students.”

After a few more exchanges, Harmon asked, “Do you believe that money was entrusted to EYS to be a steward of that money for the students?”

“Yes, I do,” Brock replied.

Auditors: ‘This was public money for the kids’

Other witnesses called this week also testified about how Epic Charter Schools and Epic Youth Services handled the learning fund. Similar to the issue of Epic and EYS’ separation, another issue alleged by prosecutors and denied by the defense is whether the learning fund contained public or private money.

Two witnesses from the State Auditor and Inspector’s Office who worked on the investigative audit into Epic testified at length Wednesday and Thursday about the learning fund.

“Our understanding was that the learning fund was public money — taxpayer funds,” Brenda Holt, the SAI director of forensic audits, told prosecutors on Thursday.

Another auditor testified about numerous transactions from the learning fund to EYS’ general operating account, which was used to pay the company’s owners.

“When they were transferring money to an outside business account (…) it was concerning because this was public money for the kids,” said Salesha Wilken, the SAI’s investigative audit manager.

But Harris and Chaney’s defense team attempted to make a point that the learning fund contained private money because it was housed in accounts owned by EYS, a private company. Additionally, EYS was contractually obligated to “administer” the learning fund, although all of the learning fund managers were employees of the school.

At one point Wednesday morning, Wood, who represents Chaney, asked Epic deputy superintendent of finance Jeanise Wynn on cross examination whether the public school pays her salary into her private bank account.

“If you make a loan from your private bank account, is that private money?” Wood asked Wynn.

She responded that money paid to her by her public school employer is compensation, which should be considered differently than Epic Charter Schools transferring money to EYS for the learning fund.

“It is not money that is earned,” Wynn said on redirect by prosecutors. “It is money they are entrusted with for the benefit of the students.”

(Correction: This article was updated at 9:55 a.m. Tuesday, April 2, to correct reference to Josh Brock’s suspended sentence.)