The Gower Memorial Cemetery, in Edmond, is a living testimony to a family’s compassion that crossed racial barriers.

The cemetery of more than 500 plots became a free burial site for the poor who could not afford a burial elsewhere. Families would mark loved ones’ graves with tin, table tops, pieces of wood and red sandstone. Few of those original markers remain.

Situated off Covell road, between Post and Douglas, the cemetery was established shortly after the Land Run of 1889 by John Gower and his wife, Ophelia, who were former slaves. Gower was trained during slavery to be a skilled stone cutter.

“They are the ones who were trained in the hard labor work that was most important for building the nation,” his granddaughter, the late Myrtle Gower Thomas, said in an interview with the University of Central Oklahoma in 1993.

The couple had traveled from Kansas to claim the original 160 acres of wilderness.

“John volunteered to serve as a soldier in the Civil War. Many escaped slaves elected to join the Northern Army rather than to remain in bondage,” Thomas said. “He made a dugout and within the five years he had built a log cabin for his family. He had, I believe — I’m not sure of this because I’m not looking at my material — he had 33 fruit trees and he had cattle and of course his vegetables. And I’m sure this is the way many of the homesteaders, including the African Americans and the Anglos, that’s the way they survived.”

Elizabeth Miller, who was Black, was the first person buried in the cemetery, in 1896. Her husband volunteered to fight in the Union cavalry during the Civil War.

John Gower fell into a state of grief in 1921 when one of his sons died. So he deeded the property to his eldest son, William Gower, Thomas’ father. John Gower was 69 when he died that same year.

“Willie” Gower was a farmer and builder who carried on the tradition of letting families bury relatives on his homestead before Oklahoma statehood officially recognized the Gower Memorial Cemetery in 1907. He worked for Baggerley Funeral Home before passing away in 1954, Thomas told The Edmond Sun in 1990. Willie would build the caskets, dress the bodies and always said a prayer.

“You could see what they had — they had no money. But they knew how to use the earth and the materials from the earth. And I myself, my father taught us to take nothing and make something,” Thomas said to Mary Bond in the 1993 UCO interview.

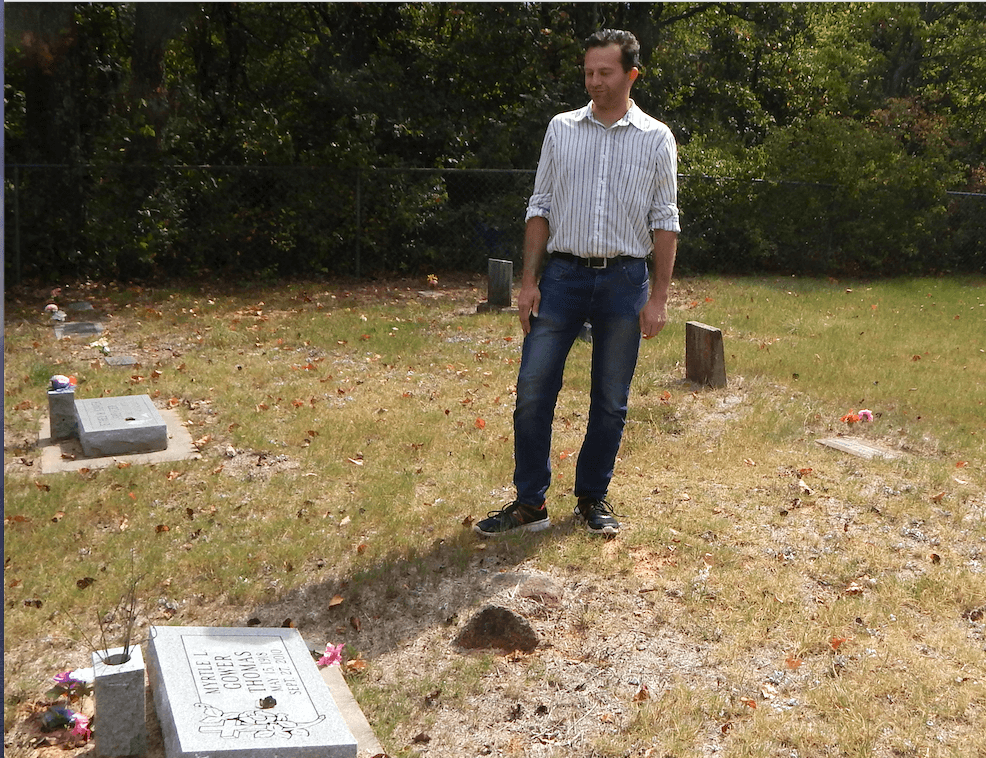

Thomas was able to place the cemetery on the National Registry of Historic Places in 1991. She was a retired Detroit school high school counselor who returned to her hometown of Edmond in 1986 with her husband, David. She set in motion perpetual care for the grounds. Thomas filled the cemetery with two acres of Bermuda grass that was cut weekly to maintain a peaceful setting.

Ten years after the 92-year-old’s death, in 2010, the cemetery continues to need regular care. Now, the city is formalizing a method of care for this historic site for the family’s consideration. Volunteers from the City of Edmond and the community recently met at the cemetery to honor Thomas’ vision.

“The Gower cemetery created for people of color in rural Oklahoma is rising once again,” said Darrell Davis, city councilman. “The grass is cut, trees are trimmed, and the worn headstones are now shining once again toward heaven. They may be gone, but we will not forget them. The Gower cemetery represents evidence of our past. Let’s reaffirm our history and be proud to continue this legacy into the future.”

Thomas’s grandson, Sherrod Wall, said he believes Gower Memorial Cemetery was and is a beacon of hope for people of all races and creeds and lifestyles.

“It is proof that despite prejudice and hate brought on by childish discrimination, Americans can appreciate one another as equals and recognize the importance of diversity,” Wall said.

Story of Stone

By James Coburn

She said you can’t always help the living,

but you can help the dead.

Now a green whisper passes over her tombstone

in the field where her mother had said,

“Don’t let weeds grow on my grave.”

Myrtle Gower Thomas —

Granddaughter of slaves, daughter of enlightenment,

the verdant ground of indigent graves

achieved greatness by your care;

between the woods, beneath the air

where the poor would bury their dead;

where persons of color rest together.

Some were placed in boxes and stacked.

Unmarked graves, crude stones,

faded markings on red rock

took form

on this field of color

where her aged Black hand reached for mine

in a steady pace supporting a delicate stride

on land her grandfather homesteaded;

a man whose color painted a Kansas regiment

against the Rebel southern fears,

now left with the ages.

John Gower would bury the dead

beside his 1889 Oklahoma dugout;

a place where poor white and black families

could rest in peace when Oklahoma territorial

burials were segregated.

Now belonging to wind and turning earth,

his granddaughter Myrtle Gower Thomas,

my friend.

Among Us: Guthrie Conversation Hard to Digest

By James Coburn

In America’s heartland

there’s a small cafe in the center of town.

Folks sat to my right as I looked around.

“Heavenly Father, bless this meal

we are about to eat,” came free with my meal.

I never ordered the conversation

from that corner booth.

“All Democrats are communists —

you know that,” said the man

wearing a straw cowboy hat.

His wife continued eating her

dinner bread, then scraped her

spaghetti bare.

“Let the Blacks vote and we’ll be singing

the Black national anthem.

Nothing but trouble.”

I wondered if his God heard this

part of the prayer;

urgent to carry around —

his voice to the rest of town.

He chewed his words, swallowing

“everything was fine

until Black lives got out of hand.”

I want to think his language is disposable

as the food he prayed for.

But he continued his walk out the door

spraying his blessing in the air.