The removal trial of suspended Oklahoma County District Judge Kendra Coleman will enter its third week Tuesday, and her defense team is expected to call more witnesses challenging claims that the first-term judge exhibited poor judicial temperament toward domestic violence victims and others appearing in her courtroom.

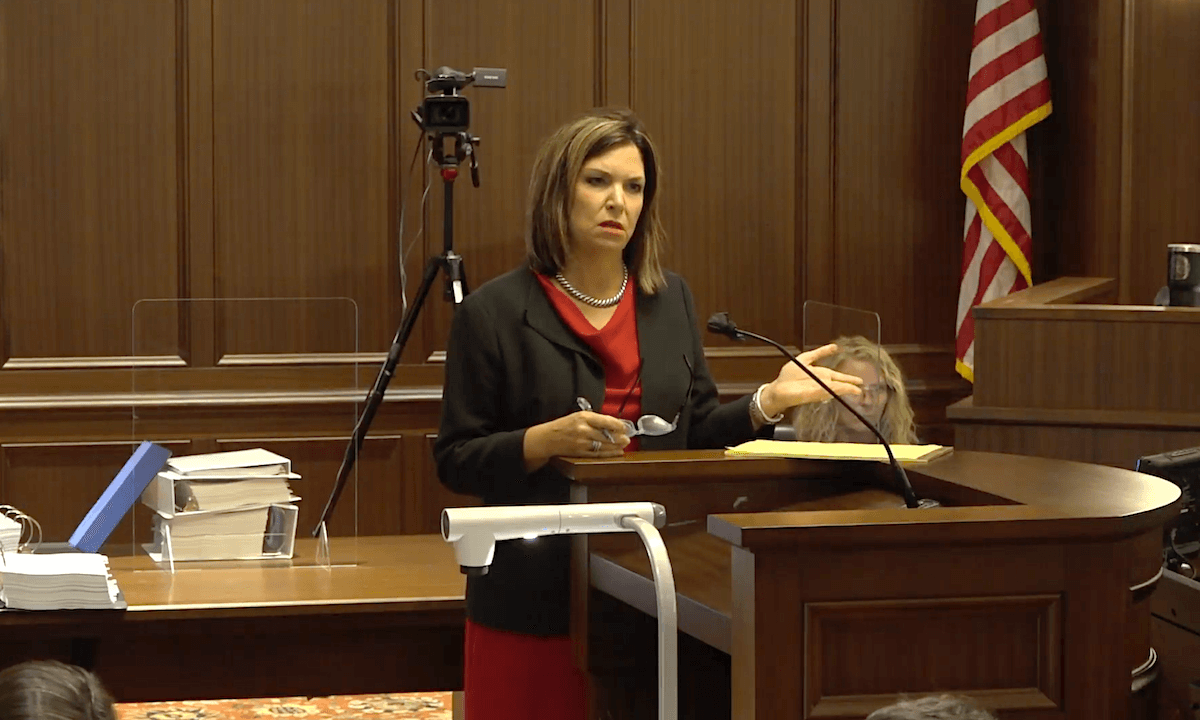

The trial panel of the Court on the Judiciary — a jury of eight judges and one attorney — denied Coleman’s motion to dismiss the case Thursday by a vote of 7-2 after appointed prosecutor Tracey Schumacher concluded the prosecution’s case.

Several domestic violence advocates who filed judicial complaints against Coleman testified for the prosecution last week.

Laura McDonald, a victim’s advocate for the YWCA, testified that she observed Coleman “mocking” and “berating” persons in her courtroom. McDonald filed a complaint with the Council on Judicial Complaints in the first week that Coleman had been assigned to handle victim protection order cases.

“I felt like from what I had seen those three days that the behavior was such that I needed to speak for those who couldn’t speak for themselves, and my hope was that somebody would address it and it would get better,” McDonald said.

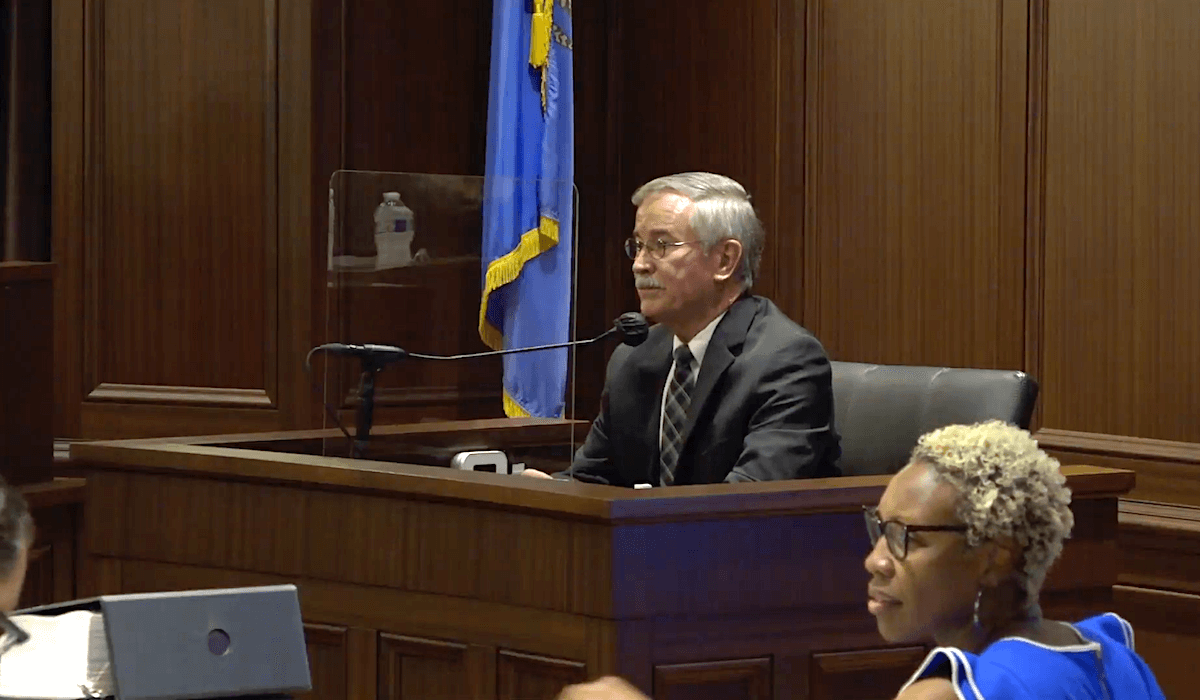

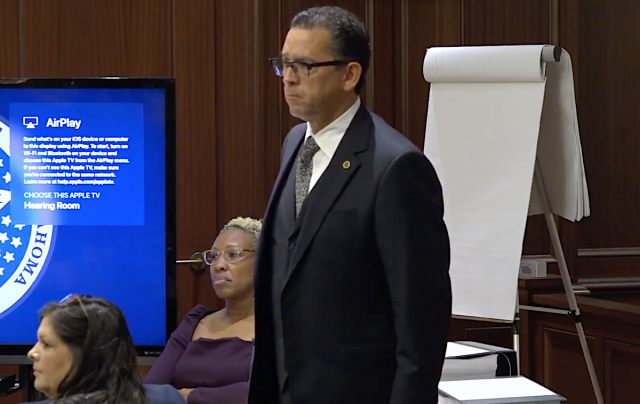

Defense counsel Joe White suggested there was an orchestrated effort by local domestic violence advocacy groups affiliated with the Palomar Family Justice Center to oust Coleman before giving her a chance on the VPO docket, an assignment made by presiding District Judge Ray Elliott in January after the state Supreme Court reprimanded Coleman for previous violations of judicial misconduct.

“A judge ought to get to run his or her courtroom,” White said. “You have that right or privilege. I don’t believe Judge Coleman has had that right or privilege given her.”

White told the jury panel in his argument on Coleman’s motion to dismiss that the victim advocates had been upset with the new judge’s change in certain procedures from what they were used to, including the seating arrangements of advocates appearing with victims within her courtroom.

He said Coleman also dismissed some VPO requests because they had not followed state law requirements in the pleadings filed.

“They don’t want change. They just want the status quo,” White said. “Whatever the law is so long as it’s favorable to them, then so be it. If it’s not favorable, they don’t like it. They wanted a rubber stamp.”

Palomar is a nonprofit agency that houses several different victim advocacy groups and counseling services at their offices in Oklahoma City’s Midtown district. It also rents space to the Oklahoma City Police Department’s domestic violence detectives.

A Palomar employee had used their organizational email account when signing a petition calling for Coleman’s removal, but Palomar Chief Operating Officer Anden Bull said during Coleman’s trial that the petition was not authorized by the nonprofit’s management. Still, Bull said, she went to see for herself whether complaints from others about Coleman’s poor demeanor toward victims was true, so she attended a VPO hearing.

“She continually made the reference that the court was not for ‘baby mama drama,’ but was for real victims of domestic violence,” Bull said. “So, it was the overall demeanor and flippant attitude that I found concerning.”

She said the behavior was serious enough she believed an immediate judicial complaint was warranted.

Also last week, Del City Police Lt. Brad Cowden testified that victims were having difficulty getting emergency VPOs from Coleman if the alleged perpetrator was jailed. Similarly, Oklahoma City Police domestic violence detective Edward Mosier testified that he recommended victims seek VPOs in other counties instead of Oklahoma County, if possible, so long as Coleman was on the bench.

Coleman defense began Thursday

Coleman’s defense began on Thursday with witnesses testifying that she exhibited no unusual behavior and treated litigants fairly.

Shalese Blue, a courtroom bailiff who attended VPO hearings, testified there was tension between Coleman and victim advocates, who had been allowed by previous judges to stand with victims at the judge’s bench and sit in an area nearest court personnel. Such actions were not allowed by Coleman when she took over the docket.

Blue said she observed no disrespect from Coleman toward victims or others. She said Coleman had to exert authority to control the decorum in her courtroom because some had acted disrespectfully toward her.

“She is not going to let anybody just say anything to her. She handled it,” Blue said.

Blue said it has been her experience that male judges receive greater respect than female judges.

“He gets more respect than when there is a woman sitting up there on the bench,” Blue said.

One of the topics of the trial last week was Coleman’s imposition a $200 fine on a woman for direct contempt after the judge denied her request for a VPO and the woman uttered the words “of course it was.”

A deputy sheriff present in the courtroom testified the woman who was denied the VPO also said back to the judge, “I suppose somebody has to get killed before it gets approved.”

‘She listened to both sides’

The claims that Coleman mistreated participants in VPO hearings are among the allegations brought by the Council on Judicial Complaints that Coleman violated the terms of her probation handed down by the Supreme Court on Dec. 3.

As a result of the new accusations, the court set the current trial on all charges, including those complaints she mistreated litigants on the criminal and guardianship dockets to which she previously had been assigned.

In representing Coleman, White has contended that other county officials are out to get her, and he called witnesses to her defense contradicting those who have criticized her.

“She was very fair. There was no difference on how she treated either side,” said Cody Gilbert, a criminal defense attorney who appeared before Coleman from January to September 2019 when she was assigned to criminal cases. “Always a big smile and was always friendly. As far as procedure, she listened to both sides and tried to reach a fair decision.”

Gilbert said Coleman was subjected to more lax treatment from lawyers than he witnessed in other courtrooms.

“She would address it, but I never did see her raise her voice, never curse at anybody. Never berate anybody,” Gilbert said.

Attorneys Orenthal Denson and Joan Lopez also testified that Coleman’s courtroom demeanor was appropriate.

“I never saw her being anything but professional with the lawyers,” Lopez said.

Lopez said she had been a supporter of Coleman’s opponent in the 2018 election, incumbent District Judge Michele McElwee, who was a former prosecutor in the district attorney’s office and had been appointed to the position by Gov. Mary Fallin.

Lopez said she was uncertain what to expect from Coleman because of her open support for Coleman’s election opponent, but she said she was pleasantly treated by the new judge.

“It was kind of refreshing,” Lopez said.

Still, Coleman was removed from her criminal docket assignment last year after Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater sought her recusal from all criminal cases, contending she was biased against prosecutors and had failed to file campaign finance disclosures with the state Ethics Commission that would have revealed defense lawyers’ contributions to her campaign.

The allegation that Coleman failed to file timely and accurate campaign disclosures is among the charges of misconduct brought by the Council on Judicial Complaints.

Prater has also filed felony tax evasion charges against Coleman. Those charges go to trial in November and are not issues to be decided in the current removal trial proceeding.

On Friday, former Oklahoma City Ward 7 Councilman John Pettis Jr. testified that Prater’s treatment of Coleman was similar to the DA’s treatment of him. Prater charged Pettis with embezzlement and tax irregularities when the councilman was running for county commissioner. Pettis said he believed he lost the election because of Prater’s actions.

After the election, the embezzlement charges were dismissed and he pleaded guilty to a reduced misdemeanor charge of failing to file a tax return, which Pettis said involved $4,512 in back taxes. But it ended his political career, he said.

RELATED

Read previous coverage of the Kendra Coleman removal trial by Michael Duncan

“I know what Kendra Coleman is going through,” he said. “If anyone knows, it is John Pettis Jr.”

Defense witness Teresa Hill, who served as campaign manager for Coleman during the 2018 election, testified that she observed Coleman on the bench and saw nothing inappropriate in her behavior.

Moreover, she said, Coleman’s election was an important message to young Black people.

“My daughter didn’t know she could be a judge,” Hill said. “So with Kendra Coleman on the bench, that does a lot for our community.”

The removal trial may conclude later this week. The nine-person Council on the Judiciary panel must reach a verdict by a majority vote on whether Coleman remains in office or is removed.

Much of Coleman’s defense is based on a contention that the Council on Judicial Complaints engaged in a biased investigation and failed to interview key witnesses that refute the charges of misconduct.

On Friday, White said in court that Coleman would take the witness stand in her own defense.

(Clarification: This article was updated at 12:07 p.m. Monday, Sept. 14, to clarify reference to an email submitted into evidence in the Judge Kendra Coleman removal trial.)