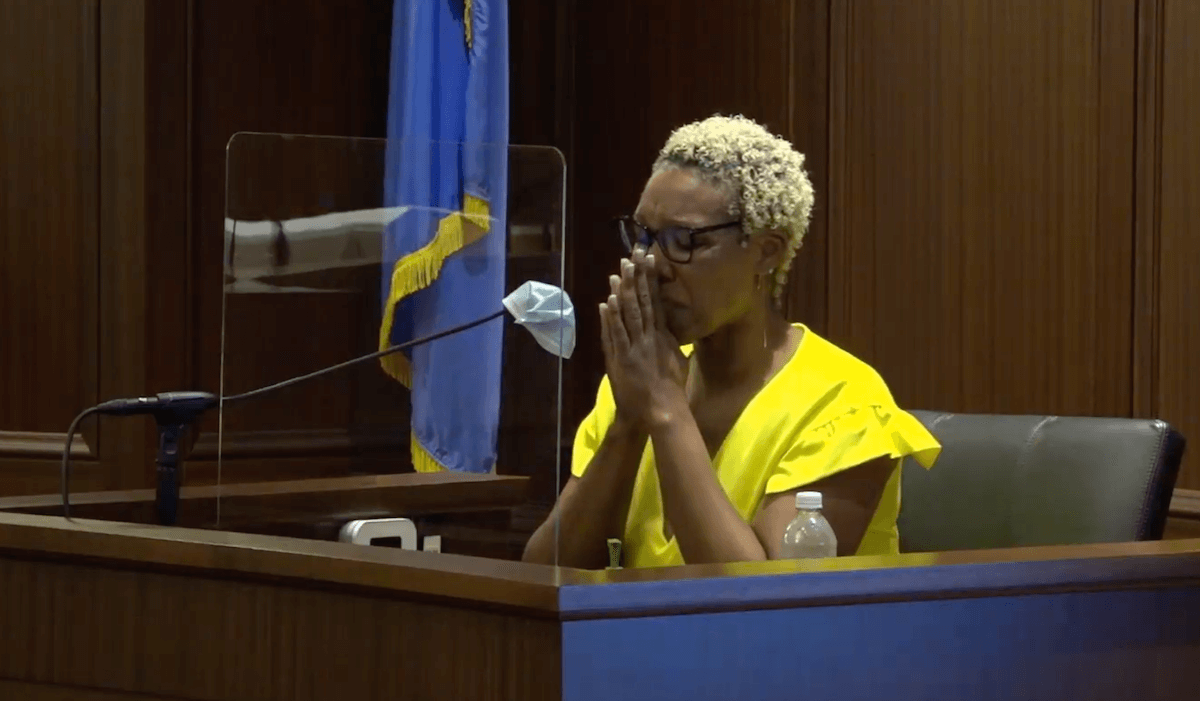

A state judge testifying in the removal trial of District Judge Kendra Coleman sharply criticized her fellow Oklahoma County judges today for spreading gossip and being untrustworthy.

District Judge Aletia Timmons described the current courthouse atmosphere among judges as “hostile” and said much of it centered around complaints about Coleman.

“I got elected to work, not to run from courtroom to courtroom spewing false, malicious gossip and cooking up petty complaints,” Timmons said. “The public sent us there to work and do justice.”

Timmons was the last witness called by Coleman’s defense counsel in the three-week removal trial of the first-term district judge.

Several other Oklahoma County district judges appeared earlier in the trial as witnesses for the prosecution, which targeted Coleman’s courtroom demeanor among other charges of misconduct as grounds for her removal.

Timmons testimony became a scathing indictment of her judicial peers, accusing them of pettiness and spreading gossip.

“Before she could even get her feet wet, they‘ve picked on her in ways that are petty, ignorant, racist and completely outrageous. It has been tough to watch,” she said.

Timmons testified that other judges assigned to the criminal dockets maligned Coleman at the judge’s judicial conferences.

“As my grandma would say, some are so low they could sit on a Kleenex and swing their feet,” Timmons said. She did not identify the judges by name.

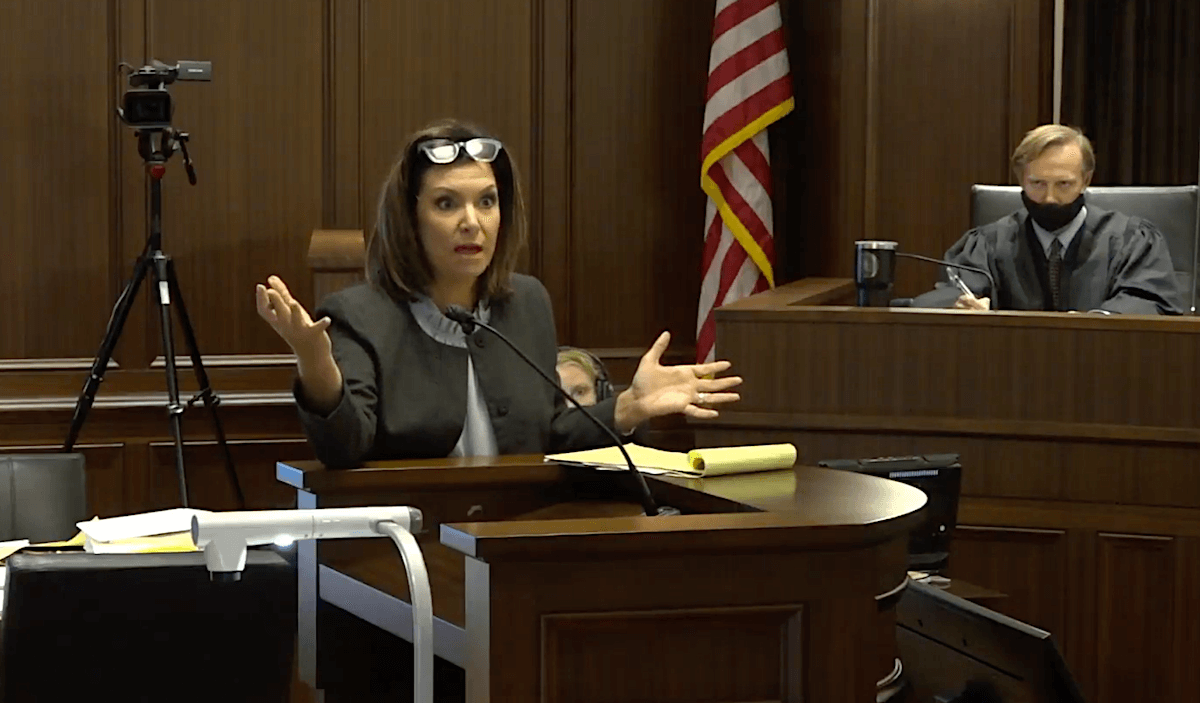

Late Thursday, the acting prosecutor for the Council on Judicial Complaints, Tracy Schumacher, said District Judge Natalie Mai and District Judge Ray Elliott would be called as rebuttal witnesses if the Court on the Judiciary allowed it. Elliott had previously testified in the prosecution’s case against Coleman, and both he and Mai appeared as rebuttal witnesses late Thursday.

Attorneys are scheduled to make their 30-minute closing arguments before the Court on the Judiciary beginning 9 a.m. Friday.

Coleman’s professional relationships a ‘pervasive’ topic

In her fiery testimony, Timmons said she became the first Black female judge to be on the civil docket in Oklahoma County history.

Coleman, elected in 2018, was the only Black district judge assigned to criminal felony cases in Oklahoma County, when she was transferred by the presiding judge following District Attorney David Prater’s efforts to have her removed from all criminal cases for alleged bias against prosecutors.

Coleman’s difficult relationship with other judges was a “pervasive” topic of several mentoring sessions that a former state Supreme Court justice had with her during the past nine months.

Former Justice Dan Boudreau — who the state Supreme Court selected to mentor Coleman in a Dec. 3, 2019, order that reprimanded and placed Coleman on probation for judicial misconduct — said his mentoring sessions revealed a “beleaguered” judge who believed she was under siege.

Boudreau was asked by the Supreme Court to conduct the sessions required of Coleman as part of a December 3 probation order reprimanding her for alleged misconduct .

Coleman was later suspended, and the removal trial was scheduled when the Council on Judicial Complaints alleged that she violated terms of the probation. But Boudreau testified that Coleman had satisfactorily participated in the mentoring sessions.

He said Coleman was, for the most part, open to his suggestions on how to be a better judge. He said she could benefit from judicial training similar to what he had received when judge. Boudreau served as a Tulsa County special judge, district judge, Court of Appeals judge and Oklahoma Supreme Court justice during his career.

He said Coleman was distraught over her relationship with other judges at the courthouse and that was a main topic of their mentoring sessions, which consisted of numerous meetings and phone calls during the past nine months.

“She felt as though she was under significantly more scrutiny than any judge in the Oklahoma City judicial district, and she felt she was not afforded the same amount of autonomy when running her docket as other judges were afforded. That’s how she felt,” Boudreau said. “She is an open and honest person, and what you see is what you get. Like me, she has flaws. But one of them isn’t duplicity.”

Victim protective order denials a focus of trial

Thursday’s proceedings opened with Coleman finishing her own testimony in the trial. She addressed several of the allegations made against her by the prosecution. One of those allegations that was the subject of extensive testimony concerned her rulings denying emergency victim protective orders (VPOs) to domestic violence victims when their assailants were already in jail.

Title 22, Section 60.3 of state statute says emergency orders may be issued when there exists an “immediate and present danger of domestic abuse, stalking or harassment.” Coleman said she interpreted the statute to mean that a jailed individual could not present such a danger.

Coleman had denied several VPOs, finding that the risk to the victim was not imminent and therefore an emergency order was not warranted. This led to several victim advocacy groups to make judicial complaints against Coleman. Witnesses from the Palomar Family Justice Center and the YWCA victims advocacy program previously testified against Coleman.

“That was my interpretation of the law when I took the bench,” Coleman said.

Coleman also admitted she had victim advocate literature removed from her office area because she needed the room for additional court personnel. Advocates had complained that Coleman’s removal of the information hampered their victim advocacy efforts.

Thursday’s final day of testimony also returned to the first chapter of Coleman’s legal difficulties, when Prater had asked her to recuse from a manslaughter case in May 2019. The case had been transferred to Coleman when the original judge, Natalie Mai, was unable to conduct the trial.

Coleman testified that Mai told her that graphic crime scene photographs would need to be admitted so Prater’s office could prove their case against the owner of pit bulls that had attacked and killed an elderly woman. Mai offered rebuttal testimony Thursday that she did not make those statements to Coleman.

Coleman’s attorney, Joe White, brought Timmons back to the witness stand soon thereafter, and she testified that Mai told her the photographs the district attorney wanted admitted in the case should be allowed for “political reasons.”

The district attorney had sought recusal of Coleman from the dog attack case after she ruled multiple photographs of the victim’s mangled body would not be shown to the jury.

“The carnage was terrible,” Coleman said. “I’ve never seen anything like that.”

Prater then became involved in the May 2019 dog mauling case and confronted Coleman about her missing campaign finance disclosure reports that he found were unavailable on the state Ethics Commission’s website.

Prater contended the defense lawyer in the dog-mauling case had been a contributor to Coleman’s campaign and that the missing reports curtailed his ability to show her bias against the prosecution. The trial was postponed, and the case returned to Mai.

Timmons testified that returning the dog-mauling case to Mai while Prater’s recusal motion against Coleman was pending allowed for the DA to “judge shop” any time he was faced with unfavorable rulings on evidence.

Coleman testified she continued to handle criminal cases involving the Prater’s office for the next three months. But then, the same case returned to Coleman for trial as part of a random assignment. Prater again sought Coleman’s recusal, but this time he requested a “blanket” recusal of Coleman from all criminal cases. He filed a complaint against Coleman with the Council on Judicial Complaints. Coleman was eight months late filing her last campaign disclosure report to the Ethics Commission.

Coleman was then transferred by presiding District Judge Tom Prince from the criminal docket and temporarily assigned to guardianship cases only.

Timmons testified the recusal motion and transfer of Coleman from the criminal docket became a topic of disagreement among judges during their private conferences. She said some of the judges were upset Prince had not reassigned Coleman permanently, a move that Timmons said would have violated court rules.

She said she and some other judges considered a grand jury indictment obtained by Prater against Coleman regarding her tax return filings was a “false indictment.” But she said others attacked Coleman’s character.

“In terms of disparaging her, they were negative and vituperative about it all,” Timmons said. “My question to them was, ‘We are judges. We’re not supposed to find someone guilty until they’ve been proven guilty, and you have evidence to the contrary sitting before you. I shudder to think what you do in the courtroom.’”

‘Prayer rally’ questioned

Also Thursday, the removal trial panel took a few minutes of pause to consider whether to allow prosecutor Tracy Schumacher to introduce evidence about notice of a “prayer rally” in support of Coleman that the judge had posted on her Facebook page Wednesday. The rally was set to occur late Thursday at the Supreme Court building where the removal trial is being conducted, after the proceeding had recessed for the night.

Schumacher argued that Coleman’s post was an unethical attempt to sway the jury panel, which consists of eight district court judges and one attorney.

“The post which she supported will ‘wrap the perimeter’ of this building. North, south, east, west,” Schumacher said. “She posted, as an offer of proof, ‘I’m overwhelmed with the love and support. You all are nothing short of amazing. Thank you so very much. I look forward to seeing you tomorrow evening.”

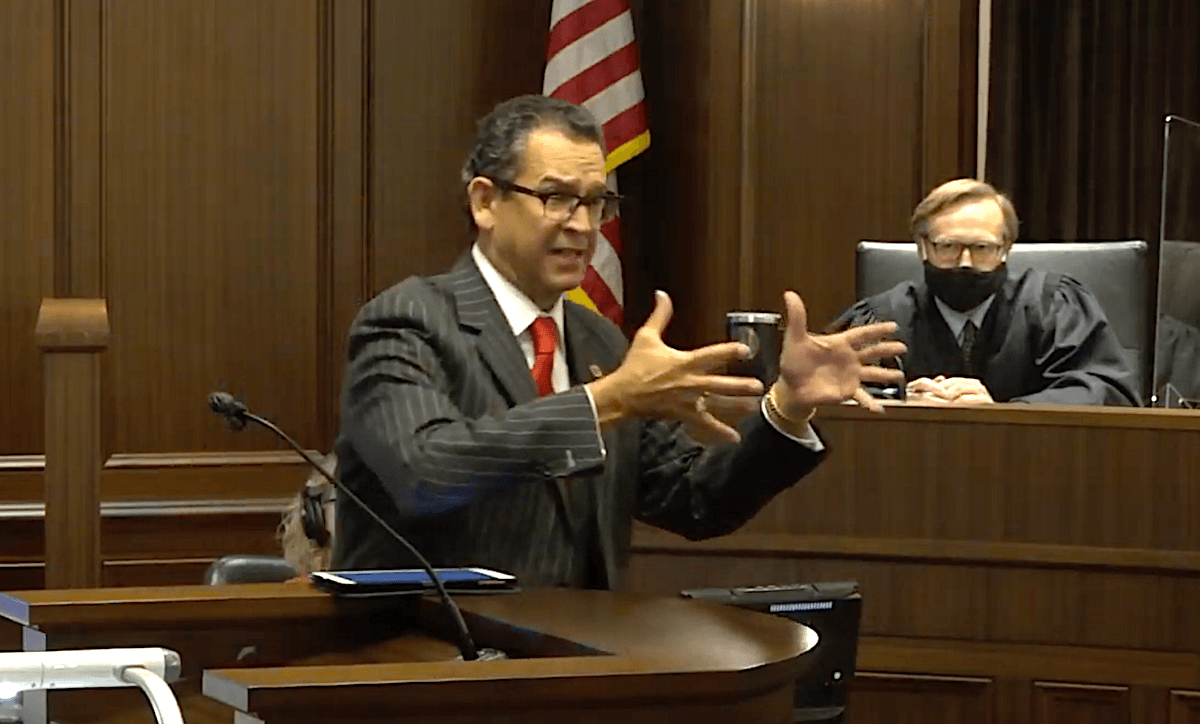

Defense attorney Joe White said he had been in discussions with state court administrator Jari Askins and made arrangements with the rally organizers to postpone the rally until 7 p.m. so the judges would be clear of the area before it began. He said evidence of the planned rally was not relevant to the ouster proceeding. The rally ended up occurring on the front steps of the Oklahoma State Capitol, with supporters walking across the street to the judicial building.

After a 10-minute recess when the panel conferred on the matter, the trial court’s presiding judge, Rebecca Nightingale, announced the court agreed with White. That ended the discussion about the rally.

Aletia Timmons: ‘It was like you were in high school’

Timmons’ testimony harshly criticizing fellow judges was an unusual exposure of disharmony at the courthouse.

RELATED

Read previous coverage of the Kendra Coleman removal trial by Michael Duncan

She also testified that Prater had threatened former District Judge Ken Watson with possible criminal charges, but testimony about those details was not permitted by Nightingale. Watson, who is also Black, was a witness in the removal trial of Coleman. He served two terms as a district judge before leaving the bench in 2018.

Timmons, a seasoned civil rights attorney before she took the bench in 2015, said her own poor treatment by other judges began on her first day. She praised former District Judge Bryan Dixon for his warm reception and professional relationship with her. But she cast serious criticism of other judges.

“It was like you were in high school and all the women were on one side ,and I was on the other. They made hateful comments — snippy, nasty, not helpful. And the men basically, for the most part, ignored your existence.” Timmons said. “Never in 30 years practicing law had I seen the disrespect I saw and experienced the first couple of years on the bench.”