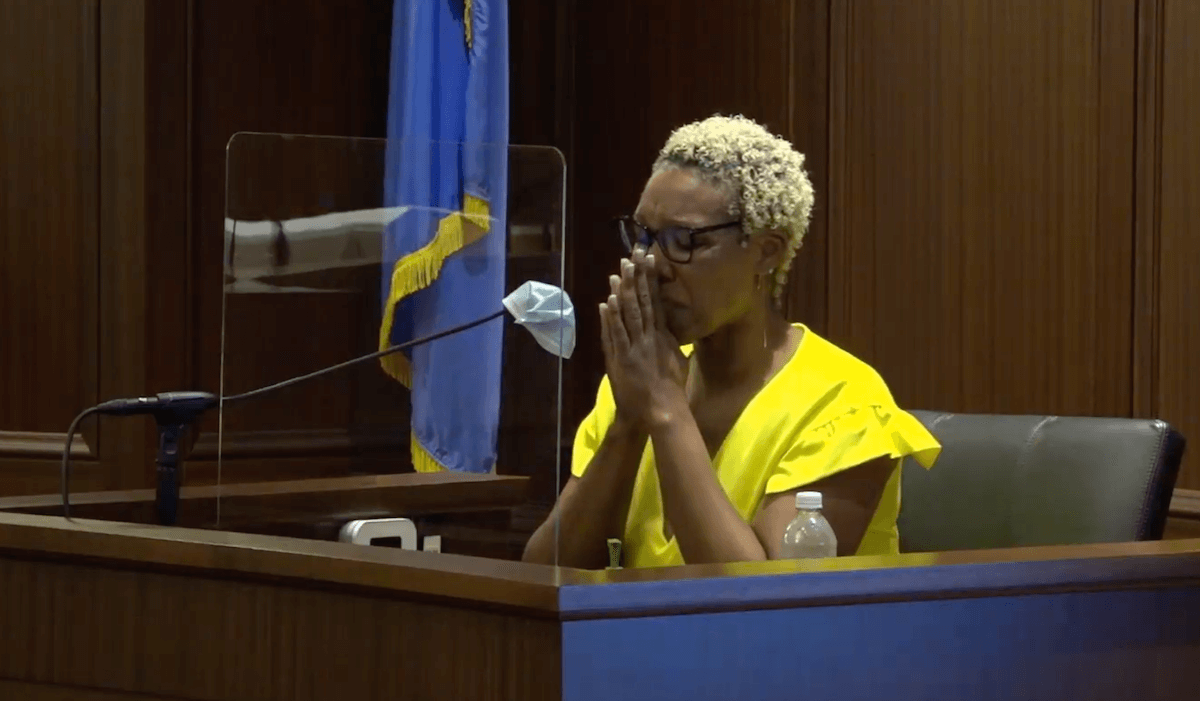

The state Court on the Judiciary trial panel has ordered suspended first-term Oklahoma County District Judge Kendra Coleman removed from the bench, finding she committed “oppression in office” and violated multiple rules of conduct governing state court judges.

The panel of nine jurors — consisting of district judges and one attorney — deliberated about four hours after the prosecutor and defense counsel ended their closing arguments in the three-week trial earlier Friday.

“It is the judgment of the majority the respondent Kendra Coleman be removed from the office of district judge of District 7, Office 9, without disqualification to hold a judicial office in the future,” presiding Judge Rebecca Nightingale announced in open court Friday afternoon.

The jury panel voted 6-3 that Coleman had committed violations warranting discipline, but only five of the jurors voted for removal from office as the punishment. Juror William Brad Heckenkemper, a Tulsa lawyer who was the only juror not a judge on the panel, supported suspension without pay for two years and one day.

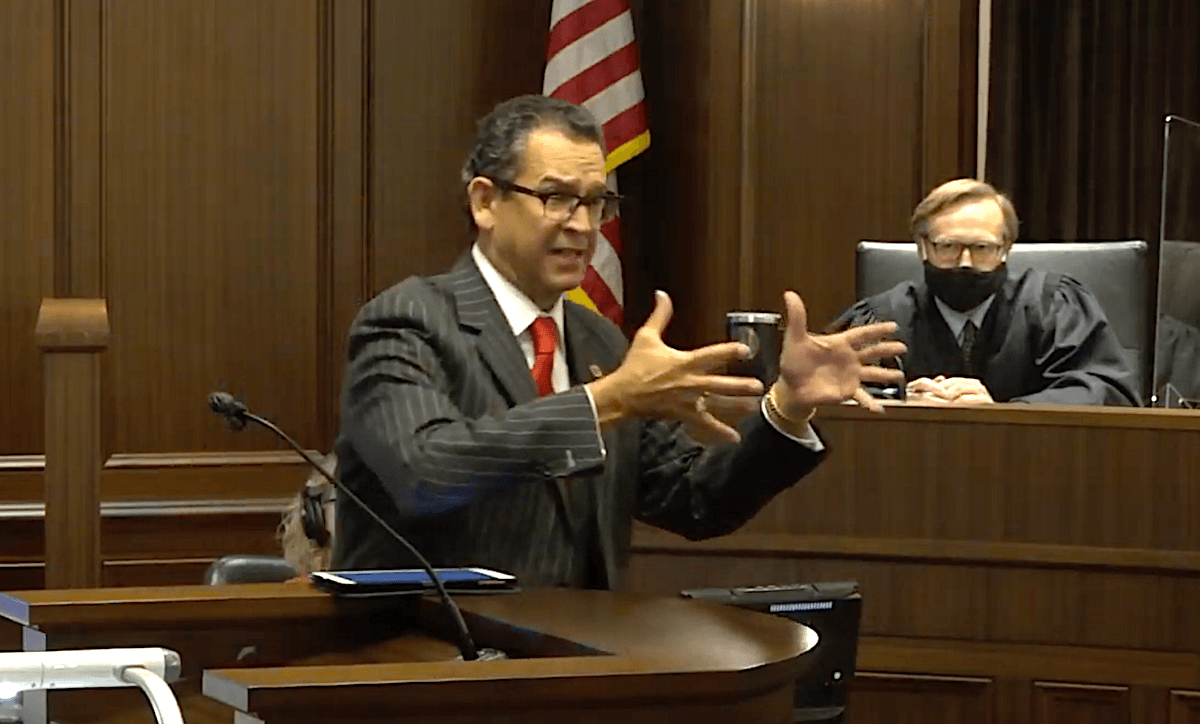

After the court returned its verdict, Schumacher said the decision was a win for judges across the state.

“Every day in the 77 counties, the judges of the district courts go to work on the various dockets — family law, criminal, civil, VPO and small claims — the list goes on and on,” said Tracy Schumacher, the appointed prosecutor. “Every day those judges try to diligently and respectfully conduct the public’s business. This ruling supports those judges and signals to the lawyers and litigants that serious, repeated and egregious conduct such as this from Judge Coleman will not be tolerated.”

Coleman’s lawyers have 10 days to file a notice of appeal to the appellate division of the Court on the Judiciary. That panel has the final authority to affirm, modify or reverse today’s trial court verdict. The state Supreme Court does not become involved in appeals from the Court on the Judiciary.

Defense counsel Kate Thompson said a decision on whether to appeal has not yet been made.

“We are obviously disappointed with the result. Right now, all options are being considered, and we will reach a unified decision,” Thompson said. “It has been a highlight of my legal career to represent such a wonderful jurist as Judge Coleman over this brief period of time. Joe White and I will always stand up for Judge Coleman. Period.”

Nightingale, the court’s presiding judge, said the prosecution had met its clear and convincing evidence burden on proof on the charges that Coleman had violated the terms of Coleman’s probation established last December, as well as ethics reporting requirements and specific provisions of the Code of Judicial Conduct.

She said the panel had voted unanimously that the prosecution had failed to prove the charge of gross neglect filed against Coleman.

Closing arguments showed nuances of case

In closing arguments, Schumacher told the court that Coleman had committed “oppression in office” by her courtroom actions, which included alleged mistreatment of lawyers and advocates for domestic violence victims appearing on a victims protective order docket.

Coleman’s defense lawyer, Joe White, argued during his closing that Coleman had only been in office for a few short months before forces at the courthouse began to attack her, an environment he said was exposed by the trial and highlighted by testimony from District Judge Aletia Timmons.

Coleman was the only Black district court judge assigned to felony criminal cases in Oklahoma County when the drama surrounding her began in 2019.

“She never had a chance to establish herself, to get her feet wet and become a district court judge and grow into being a judge,” White said.

Timmons testified Thursday that she saw Coleman targeted with disrespectful and racist gossip from other judges in the courthouse and characterized charges of tax evasion filed against Coleman by District Attorney David Prater as a “false indictment.”

The multi-county grand jury indicted Coleman on four misdemeanor counts of tax evasion in 2019, but Prater dismissed the charges and filed one felony count of tax evasion against her. She faces a November trial on the tax charge in Oklahoma County District Court.

White said the investigation of Coleman by the Council on Judicial Complaints was “sloppy at best” and failed to interview numerous witnesses who contradicted the prosecution’s case. Some of those witnesses, which included litigants, attorneys and court personnel, testified for Coleman in the trial.

Schumacher, a former district court judge from Norman who was appointed prosecutor by the Court on the Judiciary, said in her closing argument that Coleman failed at a judge’s responsibility to be respectful of those appearing before them.

“It really is a simple job. You listen to the people speak. You let the people speak. You rule on what the people speak. Period,” Schumacher said. “Sometimes you’re right. Sometimes you’re wrong. But, always, always, always must you be polite and dignified and respectful, no matter how twisted up a litigant, a lawyer or a juror — no matter how twisted up somebody gets in your courtroom.”

Schumacher said a judge is in control of his or her courtroom.

“You set the tone in your courtroom. And in the past three weeks you’ve seen and heard the evidence of the tone that was set by judge Coleman in her courtroom,” she said. “You have colleagues all over the state in 77 counties: special judges, associate judges, district judges. Those colleagues sit on that bench with various levels of training and various levels of experience when they take the bench. Yet none of them sit in that seat (facing removal) other than Judge Kendra Coleman.”

‘The life led and example set by Kendra Coleman’

Schumacher told the jury panel of judges that Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater was not behind the Council on Judicial Complaints’ investigation of Coleman, rejecting a key trial theme of Coleman’s legal defense team.

She said the council initiated its investigation after reading newspaper accounts of Coleman’s ethics reporting violations, not as a result of the complaint filed by Prater. She also said many witnesses who testified regarding Coleman’s poor courtroom demeanor had no connection to the district attorney.

“The only person ruining Kendra Coleman’s reputation is Kendra Coleman. The only person standing in Kendra Coleman’s way is Kendra Coleman. The conduct that we’ve heard over the past three weeks is as a result of the life led and the example set by Kendra Coleman,” Schumacher said. “There is a code of judicial conduct that applies to all. Every single judge in the state, to include Kendra Coleman. Yet for some reason, the ethics rules and code of judicial conduct don’t seem to apply to her, because she missed that rule or didn’t read it right. I submit to you that it does.”

Schumacher said Coleman committed “oppression in office” by repeatedly preventing witnesses and lawyers from being heard during her hearings, including Assistant District Attorney Jimmy Harmon, who appeared at an in-chambers hearing in which Prater sought Coleman’s recusal from all criminal proceedings.

Coleman was reprimanded Dec. 3, 2019, by the Oklahoma Supreme Court for judicial misconduct and placed on probation. The Council on Judicial Complaints later charged her with violating the probation, leading to this month’s trial to have her removed from office.

The removal trial also revealed Coleman owed $100,683 in federal taxes and penalties and $17,616.39 in state taxes. But her accountant testified that a payment plan with the Oklahoma Tax Commission had been reached and a similar proposal to the IRS was made.

Failure to pay the taxes was evidence the Court on the Judiciary could consider in its deliberations, although evidence whether she was guilty of the tax evasion charge filed by Prater was excluded owing to the pending criminal charge against her in Oklahoma County District Court.

Schumacher said that much of Coleman’s misconduct occurred after the Supreme Court reprimanded her, when she was reassigned to the victim protective order docket and refused during hearings to let advocates stand with their clients who were victims of domestic violence.

“Does she clean up her conduct? No. Does she act like a judge who has been publicly reprimanded to watch your conduct? No. She doubles down,” Schumacher said.

Background on Kendra Coleman legal problems

Coleman’s legal problems began in 2019 when Prater sought her recusal from a manslaughter case in which an elderly woman was fatally attacked by two pit bull dogs. She refused to allow prosecutors to show a jury the gruesome photographs from the crime scene.

Prater learned that the lawyer defending the dogs’ owner was attorney Ed Blau, who had hosted a fundraiser for Coleman during her campaign. (Her current defense counsel, Joe White, had co-hosted the fundraiser.)

Prater said he learned Blau had given Coleman $500, although Blau corrected that later to $1,000. Prater sought recusal of Coleman when he found her final campaign finance disclosure report to the state Ethics Commission had not been filed when due nine months before.

Prosecutors testifying in the Coleman trial said she dismissed the concern about Blau’s contribution when they brought it up in their request for recusal. They said Coleman commented that she had shoes that cost more than that.

In her closing argument Schumacher addressed Coleman’s alleged statements and her financial issues, including Coleman’s testimony that her lawyer was paying for her litigation expenses.

“If you’re in the hole to the IRS exceeding $100,000, the Oklahoma Tax Commission $17,000, Oklahoma County Treasurer’s office over $2,500, and you’ve got an open tab with a law firm who’s footing the bill for all these problems, maybe you shouldn’t be wearing $500 shoes,” she said.

The removal charges against Coleman also included misconduct in holding three persons in contempt and sending them to jail without conducting a hearing.

But White noted that none of the persons Coleman held in contempt were presented by the prosecution as witnesses in the trial. He also recalled testimony from Timmons that other Oklahoma County district judges, including presiding District Judge Ray Elliott, had similarly placed persons in jail for contempt without hearings, although she said the practice was unconstitutional.

Coleman had testified she held the persons in contempt because they had caused disruption in her courtroom.

White argued that the Prater recusal proceeding was when the “craziness at the courthouse” began regarding Coleman.

“This has to stop — on what you can do to bring a judicial complaint. I didn’t even know this existed when I was in law school. I didn’t know this,” White said. “I didn’t know my first five or 10 years of practicing law that you could file some kind of complaint on a judge. I thought you had to go beat them at the ballot box, like it ought to be.”

White: Council on Judicial Complaints fell short

White said the Council on Judicial Complaints failed to interview significant witnesses that contradicted some of the complaining lawyers and advocates. He said the picture painted by their stories was inaccurate without the witnesses, who were found by Coleman’s defense counsel and presented during the trial.

“When you are charged with an investigation, regardless of the person, regardless of circumstances, we aren’t Russia. We are not North Korea. We are the United States of America,” White said. “We are the U.S. of A. We defend and protect, and when we do it we do it the best we can because we want to get it right. How can you get it right when they do not go about it with an unbiased attitude?”

White said the charge that Coleman used an improper procedure in jailing persons in contempt had already been addressed by the Supreme Court in their Dec. 3 order that admonished and reprimanded Coleman.

White said at least one of the incidents brought by the prosecution which claimed Coleman had unfairly threatened contempt involved Harmon — the assistant district attorney — during an in-chambers hearing in which Prater was seeking Coleman’s recusal.

He said Supreme Court Justice Noma Gurich had already addressed that incident with Harmon and found it was merely a heated exchange between Harmon and Coleman that involved “mutual acrimony.”

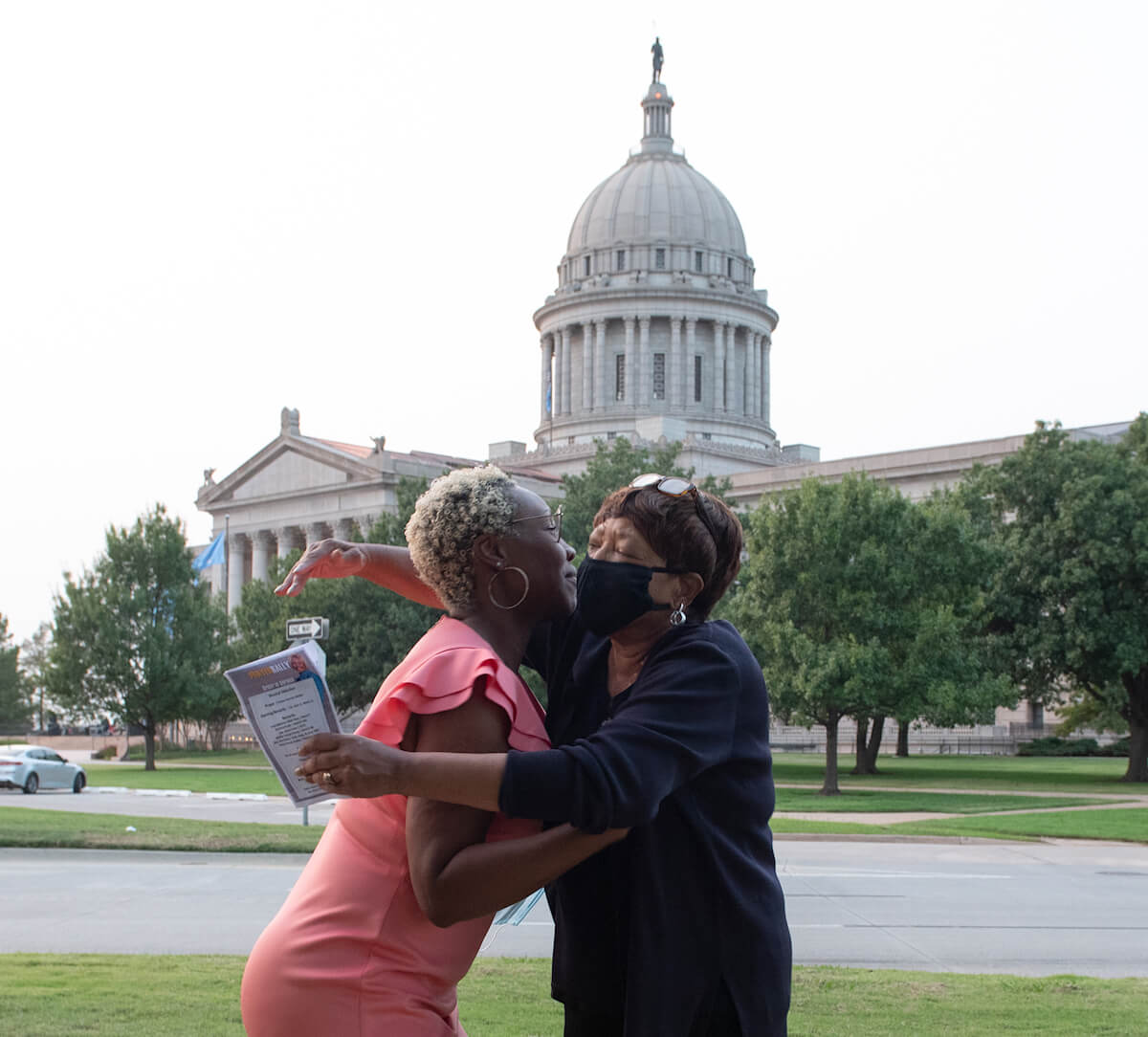

White argued that removing Coleman from office denied voters their choice of a judge. Coleman defeated incumbent Michele McElwee in 2018 to take the seat, which is one of the judge positions elected from a particular district within Oklahoma County instead of by county-wide vote. The district includes the predominantly Black northeast side of Oklahoma City.

“If you’re trying to take away 66.7 percent of the vote, aren’t facts important? That is why I say we are the U.S. of A. That’s why I say we’re not Russia, and it’s Putin’s way or the highway,” White said. “Or it’s that crazy guy in North Korea where he will kill you if you make him mad. That’s not what happens in this country. You want to mess with a vote? You’ve got to go about it right. They haven’t touched it and we’ve been exposing that here.”

The defense counsel called presiding Judge Ray Elliott’s transfer of Coleman to the difficult VPO docket “punishment.”

White said Coleman had reached a payment plan to pay her taxes due and had employed a former Ethics Commission lawyer, Geoffrey Long, to resolve the ethics disclosure issues.

He said the evidence that Coleman had purchased money orders from cash donations received by the campaign showed she was trying to create a record of the transaction and was not intending to hide anything. Ethics rules prohibit the receipt of cash contributions greater than $50 by candidates.

Coleman demeanor the focus of witnesses

Although the tax issues and ethics reports were extensively addressed during the trial, many of the witnesses concerned Coleman’s demeanor and treatment of litigants. Some witnesses testified Coleman laughed during one hearing on the VPO docket, a claim denied by her staff.

RELATED

Read previous coverage of the Kendra Coleman removal trial by Michael Duncan

But Coleman admitted to a chuckle when the courtroom spectators began laughing during a witness’ testimony regarding a hair-pulling incident between two women.

Schumacher quoted from one of the defense witnesses, former Supreme Court Justice Dan Boudreau who said his mentoring session with Coleman revealed Coleman exhibited no pretense and was “what you see is what you get.”

She said the prosecution of Coleman was not a conspiracy by David Prater to oust her, but rather was supported by lawyers and victims advocates who were mistreated by the judge.

“I do agree with Mr. White that you’ve got to protect the profession. I absolutely agree. The precedent cannot be set that one group of people cannot go after a sitting judge. I understand that and I agree,” Schumacher said. “But you don’t have one group of people here. You have many groups of people who have shown you that with Kendra Coleman what you see is what you get. They’ve shown you what they got.”

The Court on the Judiciary trial jury consisted of:

- Tulsa attorney William Brad Heckenkemper

- Tulsa County District Judge Rebecca Nightingale

- Comanche County District Judge Irma Newburn

- Garfield County District Judge Paul K. Woodward

- Wagoner County Douglas Kirkley

- Lincoln County District Judge Cindy Ferrell Ashwood

- Johnston County District Judge Wallace Coppedge

- Cleveland County District Judge Thad Balkman

- Rogers County District Judge Stephen R. Pazzo, Jr.

(Update: This story was updated at 6:15 p.m. Friday, Sept. 18, to include additional comments and the court order document.)