On Day Three of self-isolation, I could no longer taste whiskey. On Day Five, I set my thermostat to 78 degrees. By the time the aches set in, on Day Six, I knew what was going on.

That morning, disoriented, I roused myself, threw on a three-day-old sweatshirt I couldn’t smell anymore and drove across Norman, where I’m a student, to IMMY Labs for a 9 a.m. nasal swab appointment, accidentally running a red light in my delirium. The results confirmed my suspicions the next morning.

COVID-19 positive. Now what?

For the next 10 hours or so, I emailed professors, texted editors, cancelled plans and answered contact-tracing phone calls from Cleveland County. Then I retired to a routine of vegetation and extra strength Tylenol that I would continue for five days.

Looking back more than two weeks later, half of it hardly seems real.

My sense of time feels warped, like trying to recall the plot of the movie you were playing for background noise while doing something more important. Some stretches seem to go on for eternity, and others seem to have vanished from my memory altogether — washed away by fever and anxiety.

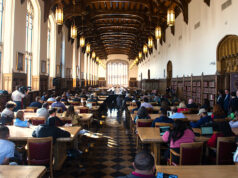

But even before I contracted COVID, it had been a strange semester. OU’s campus had lost some of its neighborly charm since in-person classes resumed in late August. Students, faculty and staff were nervous to be in such close proximity, unsure that the university’s measures of infection rates were reliable. But all of that faded further from consciousness as my body took a severe beating.

Coming out of a dream state

Regaining clarity a few days later, I started to think back to some of those early contact tracing calls.

Most of the questions they asked were easy to answer. Had I been around large groups of people in the past 14 days? I had, in class. Did I know how I had been exposed? My roommate had gotten it about a week earlier. Did I know of anyone else who had tested positive? I paused.

I did. Of course I did. But the exact names and numbers — I couldn’t count.

I had gotten COVID-19 from my roommate, who had gotten it from her boyfriend, one of several members on OU’s baseball team who had tested positive. Since I had been isolating for about eight days before my diagnosis, all of my other immediate contacts were able to evade the disease, at least for now.

But what about my classmates? How many of them had tested positive?

In my classes, there seemed to be a constant rotation of students moving on and off Zoom, having to avoid campus for various undisclosed reasons. If I had to guess, I would say it was about a quarter of my classmates at any given time.

In the days that followed my diagnosis, OU reported that there were 84 students in self-isolation after receiving a positive COVID-19 test, but that number seemed low to me.

Testing the University of Oklahoma’s self-reporting protocols

In the weeks following students’ return to campus, several members of of OU’s faculty and administration would speak out against what they saw as flaws of the school’s reporting protocols.

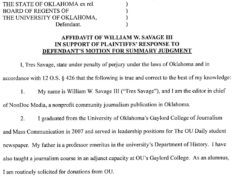

Students who test positive at the Goddard Health Center on campus are automatically recorded on OU’s dashboard, but students who are tested off campus are asked to self-report their positive results.

Unlike some other universities, OU is not enforcing this policy. Instead, student responses rely on an honor system.

Early in the semester, university administration sent a link to faculty, staff and students with instructions to complete a form should they display symptoms, test positive or have a known or household exposure.

Overwhelmed by the sheer number of responses submitted during the first few weeks of classes, Goddard fell behind on contacting students who had filled out the questionnaire. Emails were distributed stressing that the university “appreciated [our] patience” and delivering guidelines to follow until individuals were contacted by the health center, after which some students waited several weeks.

When I opened up my own form, attempting to update my status from “household exposure” to “positive test,” it would not grant me access. My case was yet to be reviewed, and I was to contact the appropriate party. There was no contact information provided.

A thorough Google search, a phone call to Goddard and an email sent to what turned out to be the wrong address yielded no results.

I finally found the answer buried in an email under a section designated for individuals who were not displaying symptoms, which I had overlooked in earlier read-throughs thinking it didn’t apply to my situation.

My IMMY Labs results were finally emailed to covidscreening@ou.edu, and I was officially a statistic.

‘I just can’t shake that lingering anxiety’

Goddard has since caught up significantly on the self-reports they have received, according to OU chief COVID officer Dr. Dale Bratzler, who is directing the university’s response. But that does not necessarily ease tensions.

At this point in the semester, it is well known on campus that the number of cases displayed on the university’s dashboard does not reflect OU’s actual community spread. But it is also understood that with the number of false test results and asymptomatic spreaders, 100 percent reporting was never an achievable goal.

For most of us, the reality that we have no way of knowing the actual scope of the disease’s reach leaves us feeling unsure of our day-to-day interactions.

The message from the top has been clear. Bratzler has told multiple news publications that the university is not making many changes within the classroom environment because “half the people who get this infection never have a symptom” and “most [students] will never meet that definition of more than 15 minutes within six feet of a person.” (However, the OU College of Law recently announced it would transition to online-only classes after Thanksgiving.) Bratzler also frequently urges those on campus to “assume anybody you contact with could be infected.”

As a college student in 2020, catching the novel coronavirus has seemed like an inevitability to me since early March. People I knew started catching it at bars, then at work. By the time the virus started making its rounds through my own four-person household, I figured it was only a matter of time.

Despite having been through the thick of it, I just can’t shake that lingering anxiety.

I hear every cough. I count the people in the room when I walk into class. My heart rate spikes every time someone sits a little too close to me on the Lloyd Noble shuttle bus.

That fear has been deeply ingrained.

(Clarification: This article was updated at 2:30 p.m. Wednesday, Sept. 30, to remove speculation about transmission.)