CLAYTON — Justin Jackson held a watchful eye on the makeshift electrical tape plug keeping his tin riverboat afloat.

If the seal didn’t hold, he doubted he would make it to the muddy banks of the Kiamichi River before the boat sank. But that wasn’t going to stop him.

“It’s just a way to kind of reboot,” Jackson said. “No matter what’s going on in your life, you get in a boat, gently float and row down the river. Whatever’s been troubling you won’t be nearly as bad.”

In a few years, Jackson fears, the river to which he has been escaping since he was a boy could be unrecognizable. He is determined to enjoy it while he still can.

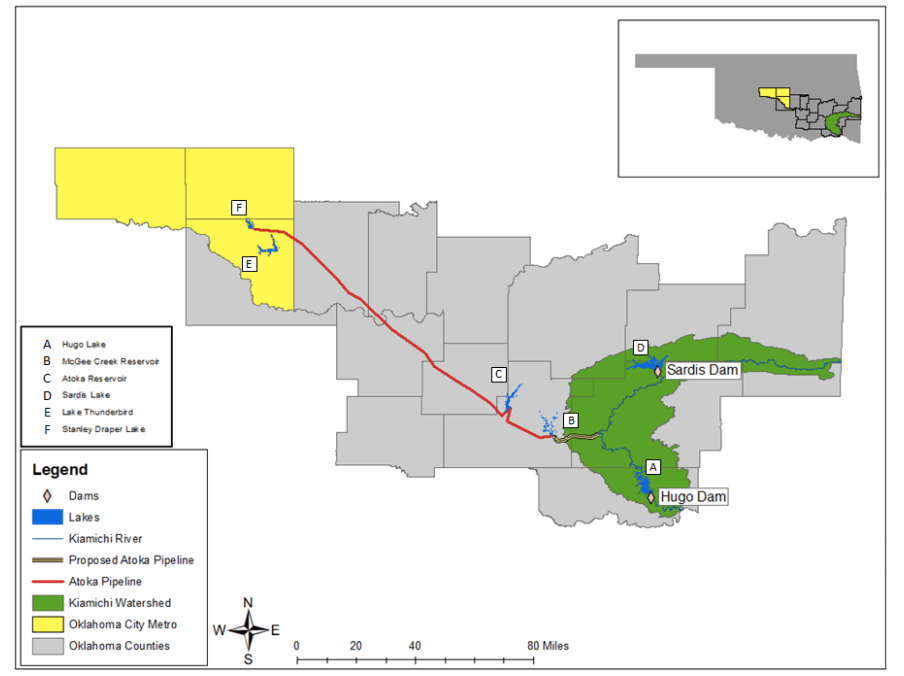

Oklahoma City’s claim on “generational water” to sustain economic growth depends on the city’s ability to acquire the resources from southeast Oklahoma that metropolitan residents covet. Securing water from the Kiamichi River has been key to implementing OKC’s plans for more than a decade. Now, nearing the finalization of a settlement agreement between the state, the city and the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations, OKC is preparing to build a pipeline that would remove 115,000 acre feet of water annually from the river and Sardis Lake, which feeds it.

With finalization scheduled for May 2022, Jackson and other members of his community fear they are running out of time to make their concerns heard.

The Lawsuit

In Pushmataha County District Court on Sept. 25, 2019, Norman attorney Kevin Kemper presented arguments for his clients — seven Pushmataha County landowners who filed suit in 2017.

Their central claim: that the Oklahoma Water Resources Board had failed to provide adequate notice about their permitting process. The group believes the water diversion permit, which resulted from the 2016 settlement agreement, relied on faulty science. With more notice, the seven southeast Oklahoma residents feel they could have addressed this issue before the permit was granted.

“We continue to work diligently to do what we can to make sure the process is transparent and the Kiamichi River basin is protected through factual science, reasonable policy and the rule of law,” Kemper said before the judge. “I hope that all of the stakeholders would work together for the benefit of all. It’s about the tribes and the state and Oklahoma City, but it’s also about everyone and everything in southeastern Oklahoma.”

But lawyers for the OWRB and the City of Oklahoma City held strong that they had followed all required law for the permit to be granted. And further, they said the settlement will provide some benefits to southeast Oklahoma communities.

“The petitioners want the court and the people of southeast Oklahoma to think that the city’s permit and Sardis operations are a loss for southeast Oklahoma, but they’re mistaken,” said Oklahoma City’s attorney, Brian Nazarenus. “The permit and the settlement agreement and the operation under it are a win-win. They’re a win for the city and a win for southeast Oklahoma and the Kiamichi Basin.”

In Pushmataha County District Court, the judge would side with the city, as would District 17 Judge Michael DeBerry, who upheld the lower court’s opinion when the case made its way to his desk in an appeal.

Now, the landowners have appealed the case to the Oklahoma Supreme Court, where it awaits a hearing.

Jackson, one of the seven landowners, said the group hopes the Supreme Court will require the Oklahoma Water Resources Board to reissue the permit for diversion of water from the Kiamichi River.

But according to Sara Gibson, a lawyer for the Water Resources Board, even if that lawsuit is successful, it would only target the OWRB’s permitting process — not the settlement itself.

“The settlement agreement itself would not be impacted,” she told NonDoc. “It would just be more board process.”

An issue born in controversy

While Sardis Lake has been prominent in southeast Oklahoma’s politics in recent years, the dispute over its water and how to access it is as old as the lake itself.

In the 1970s, the state commissioned the Army Corps of Engineers to build the reservoir that would go on to become one of the largest sources of water in southeast Oklahoma. All parties agreed that the state’s debt to the Corps would be paid off in the following years. But as the lake filled up in the decade that followed, the debt was never fully paid.

Sardis Lake was built by a generation of lawmakers that produced some of the finest water infrastructure in the country.

But by 2009, that infrastructure was crumbling.

Amidst a five-year drought and a massive population boom, Oklahoma City was struggling to secure access to enough clean water to sustain its growth. The aging Atoka Pipeline, which already moved water 117 miles from southeast Oklahoma into the city, would not be able to withstand the increasing demand.

The city needed more water and needed it fast.

Sardis Lake would become central to the city’s $1.3 billion plan.

By 2010, the state was deep in negotiations with an Oklahoma City trust to buy storage rights to about 90 percent of the lake’s water for $42 million, which would pay off the state’s construction debt.

After releasing water from Sardis Lake into the Kiamichi River, the city would build a pumping station about 39 miles downstream, where the water would be collected.

Then, the water would be pumped to meet up with the existing Atoka pipeline, which OKC would reinforce by building a new pipeline parallel to it.

“Because we already have 117 miles of pipeline to southeast Oklahoma, it makes sense for us to continue to grow that supply,” then-Oklahoma City utilities director Marsha Slaughter said in 2014. For her and other Oklahoma City officials, sharing the state’s water seemed obvious.

“When you run out of water, you can no longer grow economically or maintain your ecology,” said Craig Keith, a lawyer for the Oklahoma City Water Utilities Trust. “The city’s forefathers were attuned to how not only the city, but the state, would grow because Oklahoma City is a major economic engine for the whole state.”

The city’s plans were rolled out in 2010.

Shortly after, things began to fall apart.

A legacy of challenges

The deal was protested by residents, businesses and two Native American tribes almost immediately. By the following year, the city’s plan was facing its first major legal challenge.

In 2011, the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations filed a lawsuit against the city, the Oklahoma Water Resources Board, the Oklahoma City Water Utilities Trust and then-Gov. Mary Fallin. To the tribes, the agreement infringed upon their federal right to ensure the sustainability of their treaty homelands, including the sustainability of the water on which those homelands depend.

The lawsuit was settled in August 2016, but it would delay OKC’s plans for the next decade.

However, it featured some necessary provisions for environmental well-being of the Kiamichi River and Sardis Lake, including an enforceable measure to ensure the river maintains at least a 50 cubic feet per second flow during diversions.

According to a statement from the Choctaw Nation, “there was a strong need for the tribes to protect the water from overuse or improper use, as well as securing water for [their] local communities.”

To them, the settlement was extremely successful.

These sentiments were echoed by current Oklahoma City utilities director Chris Browning. He told NonDoc that the agreement included balancing provisions, put in place to prevent the city from needing to overdraw water from the Sardis Reservoir.

“We’re going to balance how much water we take out of Hefner, and Canton on the northwest side, and Overholser,” Browning said in reference to lakes, “and how much water we take out of Atoka and McGee Creek and Sardis.”

Further, the utilities director argued that building a new pipeline will be economically beneficial to all of the small towns along its path.

Oklahoma City’s acquisition of the southeast Oklahoma water also ended a decade-long battle between Oklahoma and Texas for the water that eventually flows into the Red River. For the settlement’s proponents, the framework the agreement establishes for the future sale of the water is key to ensuring that Oklahoma’s continued growth is not secondary to that of neighbors to the south.

But the agreement did not satisfy the concerns of many of the Kiamichi Basin’s residents.

Kenneth Roberts, a chemistry and biochemistry professor and the president of a grassroots organization called the Kiamichi River Legacy Alliance, grew up along the river’s banks.

For him, the numbers used to produce the 2016 settlement agreement do not make sense.

“I cannot figure out why they used data predating the construction of Sardis Lake when we have documented evidence that the lake reduced the Kiamichi’s flow,” Roberts told NonDoc.

Roberts is concerned that implementing drastic changes to the Kiamichi’s flow could shock the river’s ecosystem.

This is a familiar fear to the Kiamich Basin’s residents.

Dale Jackson, Justin Jackson’s father, said he will never forget the devastating effects Sardis Lake’s construction had on the local environment.

“I remember when I was a youngster that my dad and I would come down here, and we would harvest bullfrogs,” he said looking out over the Kiamichi’s babbling rapids. “Because they were a certain delicacy, you know — the frogs’ legs. And then, when the dam was put in out there for Sardis Lake, it caused an unnatural up-and-down of the river. And therefore, the bullfrogs disappeared.”

But Craig Keith, the OKC Water Utilities Trust attorney, told NonDoc the pre-Sardis data was used to determine the river’s natural flow.

“The historical flow before you were diverting, it is a more accurate representation of what the natural condition is than after it’s been manipulated,” he explained.

This data was used to determine the amount of water OKC would have to allow to flow past its diversion point while removing water from the river. The issue was a central demand of the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations in their lawsuit.

Keith said it is important to keep in mind that the scientific models the agreement relies on have already been heavily scrutinized by the two tribes.

“They spent months and months with our model, making sure that it was accurate,” he said. “They were very cautious about how the water was going to be used.”

But Roberts said he would like the chance to see the science done differently, incorporating more current numbers.

“We’ve said that all along — just do the science first,” Roberts said. “And then we’ll back down. We just want to make sure that the river will not be harmed.”

A call for political action

Justin Jackson has a clear vision for what he thinks the land surrounding the Kiamichi River and Sardis Lake can become. For an example, he had to look no further than Hochatown, just to the north.

Once a small community, Hochatown now boasts a thriving tourism industry, bringing much needed money and attention to needs that had long gone neglected. Hochatown’s main draws: water and mountains — something Pushmataha County has lots of.

“Have you been to Hochatown? Good luck getting a cabin there,” Jackson said. “We could duplicate what that town has done right here in Clayton. Logistically, we’re an hour closer to Dallas (and) Fort Worth, and we’re easier to get to.”

The southeast Oklahoma native said he has known the Kiamichi River’s potential since he was a young boy, spending time on his family’s land, which borders both banks of a large stretch of the river.

“We were planning on being the next Hochatown, and we easily could be,” Jackson said. “But we have to have our water secure first. Who wants to come in here and put in a substantial investment without knowing the future of the water?”

Should the agreement between Oklahoma City and the tribes be finalized, the city hopes to begin diverting water from the Kiamichi River by 2035. According to Jackson, if investors are unsure of the longevity of the area’s water and landscapes, it is unlikely they will take a chance on his hometown. Having to wait 15 years for potential investments could put the community significantly behind their competitors.

“I know they say there will be studies,” said Jackson, who ran for State Senate District 5 in the area. “But why take the chance? I say leave well enough alone.”

However, Oklahoma City and the Oklahoma Water Resources Board have both stressed that the settlement agreement will provide for sufficient river flow and lake levels to maintain healthy tourism growth. That would be good news for Pushmataha County, which is among Oklahoma’s most economically disadvantaged counties.

In 2010, the county’s per capita income hovered around $15,490 — about $7,000 lower than Oklahoma’s overall average. By 2019, the county’s numbers had jumped to around $22,000 per resident. Still, about half of Pushmataha County residents under the age of 18 live below the poverty line.

However, for residents of the rural county, growing tourism has brought a significant improvement in the region’s employment rate.

“The lakes and the rivers and the streams are our lifeblood,” said Randy Coleman, who also ran for SD 5 this year. “That is what is making our money. Everybody in my district is affected by water. And tourism has brought in so many dollars that we are now catching up with the rest of the state.”

According to research released in January, tourism spending hit a record $9.6 billion in Oklahoma in 2018. This is up 7.3 percent from 2017.

“Travelers are figuring out what those of us who live here have known all along — Oklahoma is truly an incredible place,” Lt. Gov. Matt Pinnell told the Shawnee News-Star. Pinnell is also the state’s secretary of tourism and branding.

The county’s newly-elected state senator, George Burns, told NonDoc that “protecting the district’s water [was] among [his] top concerns” in October.

Jackson said he and his neighbors need the help of politicians like Pinnell because the battle ahead of the group is “like David fighting Goliath.”

“I know as long as we have a legal leg to stand on, we’re going to fight for the water and the natural resources that surround it,” he said. “It’s the crown jewel of the state, the water and the mountains. It’s our greatest resource.”

Video of the Kiamichi River