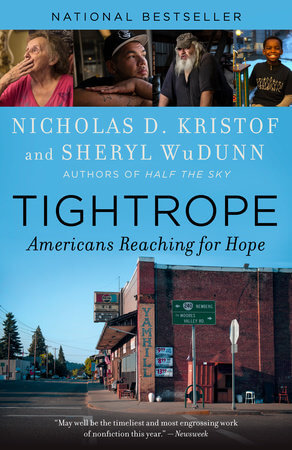

Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn’s Tightrope: Americans Reaching for Hope begins in Kristof’s hometown of Yamhill, Oregon, with his childhood neighbor, Dee, hiding from her husband, who is shooting at her. Kristof and WuDunn, who are married, later visit Dee in Luther, Oklahoma. She is there with her only surviving son, an ex-convict who struggles with addiction. She used to have four other children, but they have all died and are buried in Luther.

Tightrope uses the lives and losses of Kristof’s childhood friends from Yamhill as a lens for exploring the American epidemic of so-called deaths of despair, caused by addiction and depression. These deaths have been rising nationwide — partly owing to the opioid epidemic — and Oklahoma, where part of Kristof and WuDunn’s exploration takes place, is no exception.

As the authors search for an explanation of what went wrong with the American Dream, which was so vibrant in the 1970s, they bring a sorely needed empathy to the topic. What they uncover is a working class that has been slowly eroded by the loss of resources and opportunities and a flood of drugs. They also trace these slow societal shifts to the recent surge of Trumpism.

Tightrope identifies four, intertwined factors that have driven the rise in deaths of despair: the disappearance of good union jobs; the epidemic of Oxycodone, meth, heroin, crack and fentanyl; the War on Drugs; and the rupturing of families by mass incarceration for drug-related offences. These factors, the authors argue, have undercut social capital, damaged families and deprived children of role models.

The book draws upon Nobel Prize winner Angus Deaton’s research documenting how the poverty and bad health of millions of Americans “is as bad or worse than that of people in Africa or in Asia.” It explains why laid-off auto workers do much better in Ontario, where they have properly funded and up-to-date job training for those who lose their jobs, than in Michigan. And it makes us face the fact that 115,000 children in America are homeless on any given night.

Rather than seeking appropriate solutions through teamwork — drawing on community values and basic governmental programs such as health care for all, early education and job training — many Americans have resorted to blaming the very people who have suffered most from these changes.

The decline of the working class

In the mid-20th century, towns like Yamhill benefited from the New Deal and the GI Bill. The government invested in people (at least in white people — Black families were largely excluded), building hopeful futures and subsidizing the development of housing. Most families’ wealth comes from their houses, and government subsidies increased property values (and segregation), which in turn increased the property-tax revenues that funded (white) public schools, opening up higher-education opportunities. The 1960s’ Great Society tried to extend that upward cycle to everyone, prompting a conservative backlash.

The horrific decline of life expectancy of working-class people, who were the backbone of the industrial economy, began with 50 years of wage stagnation. The loss of good-paying jobs undercut bread-winners’ sense of self-worth. Families cracked under the strain of deindustrialization, undermining the ability to nurture children and pass on resilience.

A market-driven, global economy, with its cost-cutting and just-in-time trade routes, helped fuel extreme inequality, and America’s resiliency was further undercut as the social safety net was shredded. When young people made bad decisions, America no longer offered as many second chances.

Tightrope explains how the elites used their political power to grow dramatically richer, resulting in white workers feeling they had to battle people of color and immigrants for a shrinking share of the pie. Those inequities were products of successful propaganda campaigns portraying the free market as the solution.

Outright corruption also devastated an unconscionable number of lives. For instance, Oxycodone was branded as a safe painkiller. Hundreds of thousands of victims of legal and illegal painkillers got hooked after Big Pharma persuaded doctors to prescribe excessive amounts of pills that the drug companies knew were dangerous.

Tightrope draws on Isabel Sawhill’s The Forgotten Americans and focus groups conducted by the Republican commentator and pollster Frank Luntz to explain how white working-class grievances contributed to the Trump presidency. With the decline of jobs, people’s sense of status was threatened, the authors argue. People in declining communities felt ignored and disrespected. The combination of unexamined structural racism and the skillful playing of the race card encouraged white workers to blame immigrants for supposedly cutting in line, depriving them of the ladder to respectability.

The question now is how to get out of this mess. Seeking solutions, Kristof and WuDunn go to Tulsa and talk with the George Kaiser Family Foundation’s Ken Levit and others about one thing that has been shown to work: replacing despair with hope. For instance, the Kaiser-funded (and state-rewarded) Women in Recovery program, which provides a prison alternative for women convicted of nonviolent drug-related crimes, has a recidivism rate of 4.5 percent, far below the 16 percent state average reported in 2012. The Women in Recovery program is expensive, but its investment of $28,000 per person has the potential to save millions of dollars and an untold number of lives.

Such interventions are often easier said than funded. For instance, the authors visit an Oklahoma kindergarten teacher who “fervently supports the local domestic violence intervention center, which helped her escape a brutal ex-husband who beat and choked her,” but who doesn’t regret voting for Trump even after he tried to cut funding for domestic violence prevention.

But as division in America reaches a fever pitch, the first steps toward a better future might lie in these words from the conclusion of Tightrope: “Talent is universal, opportunity is not.” Our horrible divisions were worsened by Trumpism, but they are rooted in a half century of growing inequities. If there is anything that can reunite us, surely it must include the rebuilding and expansion of the opportunities that we all valued but which many of us took for granted.