(Editor’s note: This story was updated at 4:45 p.m. Thursday, Jan. 28, to include the bylaws of the Oklahoma Information Fusion Center’s governance board. It was updated again in December 2022 to correct reference to the year the Fusion Center was created in Oklahoma.)

The Oklahoma Information Fusion Center aims to promote “prevention through awareness,” according to the motto on the homepage of its website, but chances are that few citizens are aware it exists.

The Oklahoma Information Fusion Center is one of dozens around the country instituted by the Department of Homeland Security in the wake of the 9/11 Commission Report “for the receipt, analysis, gathering, and sharing of threat-related information among federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) partners,” according to the DHS website. Oklahoma’s Fusion Center was created in 2007 by Gov. Brad Henry.

This morning, at the headquarters of the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation, the Fusion Center’s governing board held its first meeting of 2021, though you might not have known it unless you stumbled across the announcement on the Secretary of State’s website, as NonDoc did.

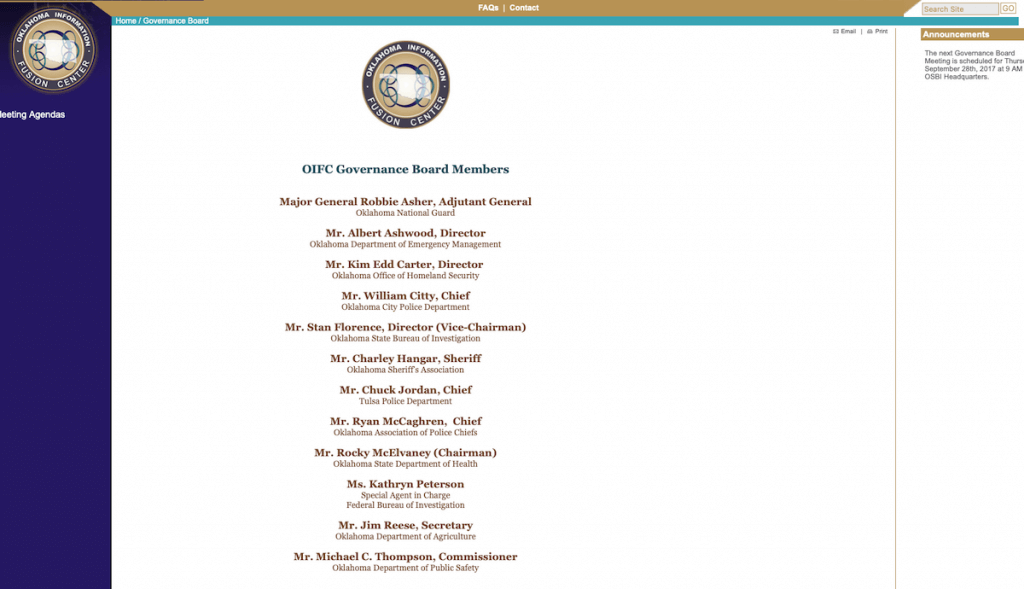

The Fusion Center’s own website doesn’t appear to have been updated since 2017, judging from the latest posted meeting announcement and the listed board of governors that includes William Citty and Chuck Jordan, former police chiefs of Oklahoma City and Tulsa, both of whom are retired. Former Secretary of Agriculture Jim Reese, who departed that post in 2019, is also listed as a board member, as is former OSBI director Stan Florence, who resigned in 2018 amid allegations of incompetent leadership.

The Fusion Center governance board’s bylaws, embedded at the bottom of this story, list the required members of the board.

No quorum, no meeting

The meeting Thursday morning started late but was brief, as only about half a dozen board members were present, falling short of quorum. Rick Adams, the director of OSBI, said the meetings are usually well-attended, but he said many board members were attending an event at the State Capitol.

Because of the low attendance, the board could not conduct official business, but OSBI Lt. Michael Dean, director of the Fusion Center, did provide an update on the center’s activities. Those activities included producing more than 800 reports and other products during 2020 and releasing an app called SeeSayOK, which allows citizens to report suspicious activity.

Dean also mentioned that the Fusion Center had been called on to assist with the response to the riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6.

“We were stood up already on Jan. 5 anticipating something may happen,” he said. “Of course we watched it, and then we stood up the Fusion Center through the 21st, manning it until things seemed to settle down.”

Three analysts with the Oklahoma Information Fusion Center gave short reports on the center’s threat assessment work. A specialist in cybersecurity noted an increase in cybercrime in 2020, including COVID-19-related unemployment fraud and phishing schemes related to the pandemic and the 2020 election. An analyst focused on transnational criminal organizations said those organizations in Oklahoma operate mostly in narcotics, and that meth is the drug of greatest concern. A terrorism specialist reported that the greatest threat of terrorism is currently linked to domestic extremism.

A target of criticism

From their early days, Fusion Centers have been the target of criticism from across the political spectrum. Organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union and the Cato Institute have critiqued the centers for overreach in monitoring citizens.

A 2012 U.S. Senate investigation led by Oklahoma Sen. Tom Coburn found that Fusion Centers had “not produced useful intelligence to support federal counterterrorism efforts.”

“The Subcommittee investigation found that DHS-assigned details to the fusion centers forwarded ‘intelligence’ of uneven quality — oftentimes shoddy, rarely timely, sometimes endangering citizens’ civil liberties and Privacy Act protections, occasionally taken from already-published sources and more often than not unrelated to terrorism,” the report said.

On Jan. 26, the journalist Ken Klippenstein published a story in The Nation about open records requests that, through heavy redaction, showed Fusion Centers tracking “criminal activity (supposed or otherwise) so mundane it’s at times comical.”

Those involved in Oklahoma’s Fusion Center say that is not the case.

Adams, the OSBI director who is on the Fusion Center governance board, said the center has been involved in preventing major events.

“You have no idea how many things you might have prevented that you’ll just never know about,” he added. “You know, you call a sheriff’s office up and say, ‘Hey, we’ve got information that there might be a school event happening someplace and we need somebody to go out and look and see what’s going on.’ So he sends a couple officers to drive by the front, and it doesn’t happen — just from the visibility of having someone there.”

Dean, the Fusion Center director, said the Fusion Center provides analysis that other law-enforcement agencies don’t or couldn’t afford.

He said he has heard the criticisms of the Fusion Centers’ work but doesn’t agree with them.

“First Amendment rights, Second Amendment rights, that is what we are out to help protect is the First Amendment rights. We do not violate them,” he said. “We have things in place to make sure those don’t get violated and the information getting sent out and who has access to that information.”

He added that he doesn’t believe the Fusion Center’s work is frivolous, as Klippenstein’s story suggests.

“We are here to protect United States citizens and Oklahoma citizens from threats of violence,” he said. “That is what we are looking at.”

Downstream from the Fusion Center sits all the law enforcement agencies around the state that receive the reports and information that the center pulls in and processes.

Beckham County Sheriff Derek Manning sits on the governance board and says his interaction with the center as a sheriff is infrequent, but he does think it’s important.

“When it does occur, it’s important information that you have a difficult time getting anywhere else,” he said. “And a lot of times, you don’t even realize it. What I’ve learned is you don’t even realize some of the information you receive has come from the Fusion Center, the way it disseminates down through some of the different levels.”