Would a long-discussed proposal to “unify” three powerful law enforcement agencies improve or politicize the ability to investigate and prosecute public corruption cases in Oklahoma?

Lawmakers and law enforcement lobbyists are debating that question this year in the form of SB 1612, a controversial measure called the Oklahoma Department of Public Safety Unification Act, which advanced out of the Senate Appropriations and Budget Committee on a 10-9 vote Wednesday.

It would bring the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation and the Oklahoma Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs under the Department of Public Safety and under the direction of a single public safety commissioner. OSBI would move from being a “requester agency” — meaning sheriffs, police chiefs, the attorney general and even the governor must ask OSBI to pursue an investigation — to a proactive agency with statewide jurisdiction to investigate criminal behavior.

Concerns about the bill include whether the qualifications for the proposed mega-agency’s commissioner are too ambiguous and whether the 11-member governing board tasked with hiring the commissioner would be vulnerable to political influence. A new $100 million joint training facility is also proposed.

Exactly how public corruption cases would be handled and by whom has also been a point of contention, with lawmakers and law enforcement leaders seeking clarity about the vision behind SB 1612’s proposal to create a separate Public Integrity Division.

As described in the bill:

The Public Integrity Division is authorized to and shall be responsible for investigating any elected or appointed state, county, or political subdivision officer or employee when there is sufficient basis to suspect bribery, corruption, forgery, or perjury or any other crime related to his or her duties or related to campaign contributions or campaign financing for that or any other office.

In Wednesday’s committee hearing, former Bureau of Narcotics director and current committee Vice Chairman Darrell Weaver (R-Moore), Senate Minority Leader Kay Floyd (D-OKC), Sen. Paul Rosino (R-OKC) and Sen. J.J. Dossett (D-Owasso) each asked questions about the Public Integrity Division, such as who would determine “when there is sufficient basis to suspect” corruption and whether the Public Integrity Division would be more or less susceptible to political influence than the present Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation.

“Currently, we have a division that should be doing these investigations and sometimes has their hands tied (about) whether they can or can’t do them because they have to be invited in,” SB 1612 author Sen. Kim David (R-Porter) said in an interview. “Any time you investigate political figures, people are going to try to insert their influence to try to either get you not to investigate or to get you to look in a different direction. So you have to have a unit in place that doesn’t have to be invited in so they are not at that political whim.”

Weaver, however, fears the new overarching public safety commissioner might have his or her own political whims.

“The bottom line is that the person who has this job is going to have ultimate power over these agencies. This person would be the most powerful person in all of Oklahoma,” Weaver said in a Feb. 21 meeting of the Senate Public Safety Committee. “We could have another J. Edgar Hoover in a heartbeat.”

To complicate the matter and emphasize the importance of debate over how public corruption matters may be investigated for decades to come, this year’s legislative theatre is playing out in front of an elaborate — and intense — backdrop:

- The Dec. 17 indictment of Rep. Terry O’Donnell (R-Catoosa) and an ongoing grand jury investigation into related legislative activities;

- An investigation into whether Floyd, Court of Civil Appeals Judge Barbara Swinton and other former Seeworth Academy board members violated the law while or after the charter school’s superintendent allegedly embezzled more than $250,000 in public funding over a decade;

- A pending charging decision on the eight-year investigation into whether Ben Harris, David Chaney and their Epic Youth Services company broke the law by obtaining and spending millions of dollars of state funding sent to Epic Charter Schools;

- An inquiry into whether staff or members of the Pardon and Parole Board broke the law by improperly re-docketing individuals who had previously been denied commutation;

- A prospective lawsuit from former Secretary of Digital Transformation David Ostrowe alleging that former Attorney General Mike Hunter “weaponized” his office by “maliciously prosecuting” Ostrowe with a controversial indictment that was dropped when Hunter resigned unexpectedly months later;

- An investigation into alleged sexual misconduct by Tim Henderson, who resigned as Oklahoma County district judge in March 2021 and claims he was in consensual relationships with a pair of assistant district attorneys;

- An investigation into the financial and prosecutorial practices of Pottawatomie County District Attorney Alan Grubb;

- A state audit and potential investigation of unverified purchases of personal protective equipment by the State Department of Health early during the pandemic;

- Allegations that former University of Oklahoma regent and former Tulsa Regional Chamber of Commerce Chairman Phil Albert embezzled more than $7.4 million;

- NonDoc’s lawsuit seeking to reveal the results of sexual misconduct and financial mismanagement investigations regarding the actions of former University of Oklahoma President David Boren;

- And years worth of recent FBI inquiries into political powerbrokers and campaign finance practices in the state of Oklahoma.

“A lot of corruption goes unchecked in this state,” former Secretary of Public Safety Chip Keating told NonDoc in an interview after Wednesday’s committee hearing.

Along with David and directors of the state law enforcement agencies, Keating serves on the Unified State Law Enforcement Commission, which David and O’Donnell created in a bill last year to study the unification question and make a recommendation to the Legislature. Keating is the son of former FBI agent and former Gov. Frank Keating, who pushed law enforcement unification more than two decades ago as governor.

SB 1612 directs that its proposed Public Integrity Division “shall work with the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the United States attorneys in Oklahoma to establish and maintain a Public Integrity Joint Task Force.” (David said that language will be amended to specify the task force would operate only as needed.)

Historically, the FBI and federal prosecutors have handled Oklahoma’s most infamous public corruption cases, including the state’s Supreme Court bribery scandal, its county commissioner scandal, cases involving nursing homes, the conviction of former Senate President Pro Tempore Mike Morgan (D-Stillwater), the conviction of former Gov. David Hall and multiple indictments against former Sen. Gene Stipe (D-McAlester).

Keating said he and other USLE Commission members arranged a phone call with FBI officials while developing the unification proposal’s Public Integrity Division.

“They’re very careful. They’re very apolitical, as you can imagine. When we had our meeting with them, you couldn’t even have elected officials present. So there are very strict firewalls around the way they will talk and they will meet,” Keating said. “They are not going to endorse any product, but they have pointed to other states where they have seen things work well. And there are other states on that task force model — a joint task force with the state and federal guys.”

Keating and David both confirmed they are aware of multiple FBI and Department of Justice investigations into alleged public corruption in Oklahoma in recent years, but no federal indictments have been revealed publicly. Numerous other individuals with direct knowledge of the investigations have spoken to NonDoc about the inquiries of federal investigators.

“The FBI comes and they fish, and they do it all the time,” said a former state lawmaker on the condition of anonymity.

A longtime lobbyist echoed the statement.

“The FBI is constantly swimming around here,” he said.

‘Did it happen or did it not?’

When it comes to public corruption investigations, opponents of SB 1612’s unification effort argue that OSBI is better positioned and better able to avoid political pressure than the proposed new Public Integrity Division.

OSBI director Ricky Adams told NonDoc that his agency’s governing commission currently keeps OSBI “insulated from the political apparatus for a purpose.”

“That was so you can have independent investigations that are not focused by interests or resources or whatever,” Adams said. “You should want an a-political organization that is giving you a straight answer that has not been vetted. Nobody has tried to vet anything that has gone through here, and I believe the apparatus as proposed would make that temptation very strong.”

But Adams’ current perspective appears to differ from a 2015 report he drafted on the concept of unification when he was a colonel with the Department of Public Safety.

“The method of governance exercised over the OSBI has provided a marginal buffer from potential political pressure,” Adams wrote in that report. “However, it has further isolated the agency into operational silos of influence and never really addressed the real problem of the 1975 David Hall scandal.”

Seven years later, however, Adams is in charge of OSBI and opposed to the unification changes in SB 1612.

“Previously, it was directors being fired, pressure being put on to come up with ‘the answer,'” Adams said of OSBI prior to its current commission structure and independence. “Well, the only answer your law enforcement apparatus should give you is, ‘Did it happen or did it not?'”

Asked whether “it happened or not” regarding OSBI’s investigations of Epic Youth Services, the Pardon and Parole Board and David Boren, Adams said he could not speak about the findings of his agents.

“These things span long periods of time. There are other factors at play outside of the investigation that you have no control over. We have no control over what happens with grand juries, we have no control over what happens with other things like that,” Adams said. “We just worry about investigating the case and bringing forward the evidence we have or that we don’t have, and we present it to the prosecutor to make a determination on what they want to do with it.”

In the sexual misconduct investigations of Boren and his longtime associate Tripp Hall, OSBI turned its completed report over to former U.S. attorney Pat Ryan, who had been contracted as special prosecutor for the case by then-Attorney General Mike Hunter. Ryan, whose law firm was paid $83,380 by the Attorney General’s Office to handle the case, issued a brief statement in October 2020 saying he had decided not to present charges to the multi-county grand jury regarding Boren or Hall.

“The OSBI investigation of David Boren and Tripp Hall has concluded,” Ryan wrote. “As the appointed acting [attorney general] for this investigation, I have made the decision, after considering all relevant facts and circumstances, to not seek a grand jury criminal indictment relative to Boren’s and Hall’s alleged wrongful conduct while they were employed by the University of Oklahoma.”

Asked if he felt Ryan’s explanation was sufficient closure for the public regarding OU students’ sexual misconduct allegations against Boren and Hall, Keating replied, “No.”

“When something is concluded, it needs to be fully transparent,” said Keating, whose father serves on the OU Board of Regents.

Keating also referenced the long-running investigation of Epic Youth Services, which has caused headlines and consternation for almost a decade.

“There have been some recently that have taken eight years to handle an investigation, and as a taxpayer in the state of Oklahoma, that’s not acceptable,” Keating said. “I am looking for more transparency as a taxpayer for when we identify [an investigation] — that we viciously either exonerate or prosecute and move it on and be efficient.”

Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater is reviewing OSBI’s completed report on Epic to determine whether criminal charges are appropriate. He is the second prosecutor to review the matter within the past year.

In May 2021, a separate special prosecutor contracted by Hunter — Melissa Houston — presented information gathered by OSBI to the state’s multi-county grand jury, which returned no indictments but did release an unusual “interim report” urging legislative action to reform charter school laws. Hunter’s Attorney General’s Office paid Houston $60,340 for her work.

‘Only when it gets to the paper’

Political observers and members of the public interested in these public corruption investigations have relied almost exclusively on news reports to learn about the inquiries. Despite his law enforcement connections, even Keating told senators Wednesday that, “I read about it only when it gets to the paper.”

“In those kinds of cases, any kind of criminal case is not able to be transparent until the case is done, for a lot of obvious reasons,” he said after Wednesday’s meeting.

While law enforcement agencies typically refrain from discussing pending investigations, a new state law was created surreptitiously in 2021 to add a criminal penalty for certain disclosures about ongoing investigations.

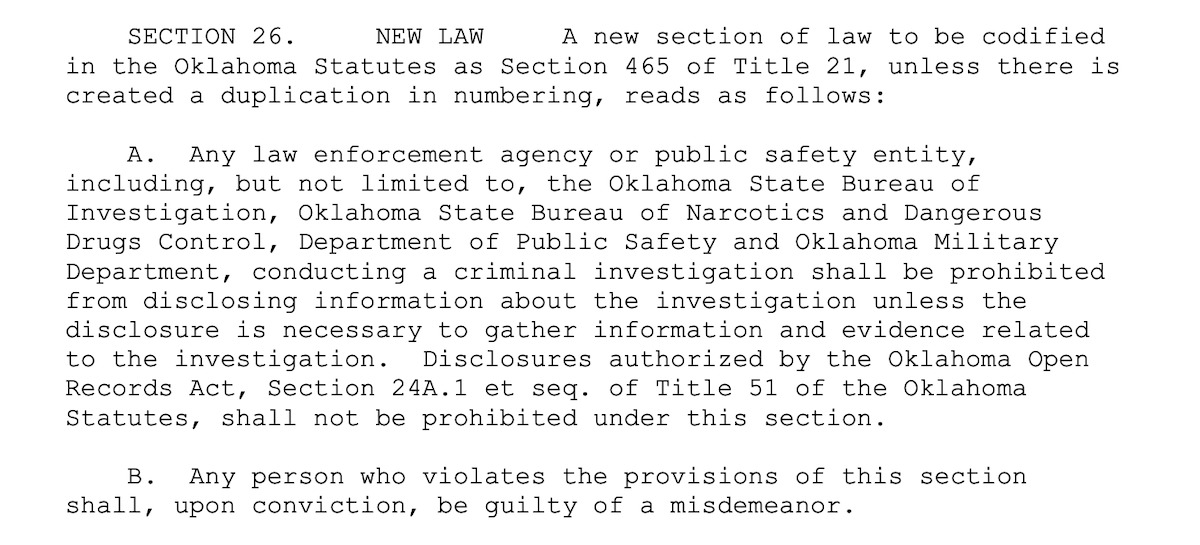

Last year, Rep. Chris Kannady (R-OKC) authored HB 2508, a 76-page behemoth rewrite of the Oklahoma Uniform Code of Military Justice. Buried within, however, was Section 26:

Any law enforcement agency or public safety entity, including, but not limited to, the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation, Oklahoma State Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Control, Department of Public Safety and Oklahoma Military Department, conducting a criminal investigation shall be prohibited from disclosing information about the investigation unless the disclosure is necessary to gather information and evidence related to the investigation. Disclosures authorized by the Oklahoma Open Records Act, Section 24A.1 et seq. of Title 51 of the Oklahoma Statutes, shall not be prohibited under this section.

Violation of the new law was established as a misdemeanor. Kannady, a judge advocate in the Oklahoma National Guard, said he included the provision in his military code bill to mirror similar requirements in federal law.

“The goal of that provision was to align the federal policy and the state policy, so it made sense to do it for any law enforcement agency in the state,” Kannady said.

While law enforcement officers may not be allowed to discuss their criminal investigations, state lawmakers are robustly discussing SB 1612’s unification proposal.

Weaver said his time as OBNDD director involved recommending charges against political figures and their family members. Although he never felt threatened politically, Weaver said he “had some borderline phone calls that came close” and that the geographical diversity and the structure of OBNDD’s board provided him support.

“Today’s system, it worked,” Weaver said. “I was never afraid to be able to investigate anybody with controlled dangerous substances or a family member or whatever. I just did my job, and I never feared having some politician calling me or trying to have me removed from my position.”

Adams agreed and said the seven-member OSBI Commission’s structure has supported his independence.

“The commission was assembled like it is now, insulated from the political apparatus for a purpose, and that was so you can have independent investigations that are not focused by interests or resources or whatever,” Adams said.

David, however, referenced the prosecution of a fellow member of her 2010 class of senators: Ralph Shortey, who was convicted by federal prosecutors of a child sex trafficking charge in 2018.

“Every incident that Director Adams brought up during our meetings about the fact he thought more political pressure could be brought upon them during these investigations — and he brought up some instances where we had a previous senator that was investigated and people were making phone calls to him, and he did the right thing,” David said. “He turned all of that over to the FBI, and the FBI was the one that ended up doing the investigation. Just like the FBI was ultimately the one that ended up doing the county commissioners’ scandal, the David Hall scandal, the Supreme Court scandal. Those were all turned over to the FBI, and any reports of any political pushback on an agency were also turned over to the FBI. So it was all handled exactly the way it should be, and none of that would change.”

‘Sick of all the political bullshit’

Some people who have recently been the subject of Oklahoma public corruption investigations would like to see things change. In particular, fast food magnate David Ostrowe has sent a notice of anticipated tort claims to the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office, former AG Mike Hunter, the Oklahoma Tax Commission and Tax Commissioner Charlie Prater.

“The powers of the AG Office, including use of the multi-county grand jury, are profound,” Ostrowe’s attorney, Matthew Felty, wrote in the notice. “Under Hunter, the AG Office became a place where political favorites went to get revenge or get a favor, and not where victims felt safe to get justice. Public corruption, magnified by Hunter’s abuse of the multi-county grand jury, cannot stand.”

Ostrowe was indicted on one count of attempted bribery for his fall 2020 conversations with tax commissioners Charlie Prater, Steve Burrage and Clark Jolley and Senate Appropriations and Budget Chairman Roger Thompson (R-Okemah) regarding a tax penalty facing former Sen. Jason Smalley (R-Stroud). Smalley had resigned in January 2020, two weeks before the year’s legislative session began, to become a senior account executive with Motorola Solutions.

Ostrowe was investigated solely by a pair of Attorney General’s Office employees: investigator Thomas Helm and Senior Deputy Attorney General Joy Thorp, who still heads the agency’s Multi-County Grand Jury Unit. (Thorp was one of three finalists for the Court of Criminal Appeals this year, but Gov. Kevin Stitt selected Tulsa County District Judge William Musseman for the position Friday.)

Thorp convinced the state’s multi-county grand jury to indict Ostrowe on Dec. 17, 2020, after only two hearings that featured only one witness: Helm, the Attorney General’s Office investigator who had conducted interviews in the case with Thorp. No other witnesses were called, and a request for additional text message records between Ostrowe, Thompson and others was still pending when the indictment came out.

“The multi-county grand jury was largely predicated on an outcome-oriented ‘investigation’ by Helm, an investigator at the AG Office who was tasked by Hunter and others with finding shreds of support for their pre-determined indictment of Ostrowe,” Felty wrote in his tort notice to Hunter and others. “When Mr. Ostrowe declined to discuss specifics, an exasperated Mr. Helm confessed to Ostrowe that he was ‘sick of all the political bullshit.’ Nonetheless, Ostrowe was indicted the next day.”

Asked if he or other OSBI leaders were even aware that Hunter’s office had been investigating Ostrowe, Adams said they were not.

Keating said the Ostrowe indictment — which was dropped days after Hunter announced his late-May 2020 resignation — shows that the state’s current disjointed law enforcement set up means “one person had the authority to do (that) and could potentially ruin people’s lives.”

“That is unchecked power,” Keating said. “I am a firm believer this (unification proposal) is 10-times better in terms of insulation not to give one person that superpower.”

Weaver said he fears the fact the new overarching public safety commissioner would have direct authority over the Public Integrity Division chief could give “one person” too much power. Still, he said he had spoken “with zero people” regarding the Ostrowe case and did not know whether it had been a proper investigation or not.

“I just hope any type of corruption in this state is investigated, because integrity of this place at 23rd and Lincoln or even in our nation, you just have to have people that believe in your government,” Weaver said.

Ostrowe told NonDoc he is “not at liberty to say” whether he spoke to the FBI about how his prosecution was handled prior to Hunter’s resignation.

O’Donnell indictment ‘wasn’t ideal timing’

Plenty of factors are complicating people’s beliefs about the law enforcement unification proposal. Many police chiefs and sheriffs around the state have felt underrepresented in the early discussions with the USLE Commission.

The prickly situation involving one USLE Commission member also strikes people awkwardly: the pending multiple-count indictment facing Rep. Terry O’Donnell, who co-authored the bill forming the USLE Commission in 2021 and who was charged by an Oklahoma County grand jury related to tag agency legislation two days after the commission released its official recommendations for unification.

“I have a tremendous amount of respect for Rep. O’Donnell. I really enjoyed my time getting to know him,” Keating said Wednesday. “I’m an innocent until proven guilty guy. I believe in that as a citizen. Was it disappointing for that to happen at that timing (while) sitting on the commission? Sure it was. But I still believe he will have his day in court and his chance to respond to it. It wasn’t ideal timing when that came out.”

Like Ostrowe, O’Donnell’s investigation originated in the office of then-Attorney General Mike Hunter and did not involve the OSBI. Unlike the Ostrowe case, however, Hunter cited a “conflict” and asked Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater to investigate O’Donnell.

Adams declined to discuss O’Donnell’s presence on the unification commission or his pending criminal charges.

Read the 2021 Unification Commission report

Loading...

Loading...

(Correction: This article was updated at 9:55 a.m. Thursday, March 10, to include the correct payments made by the Attorney General’s Office to the companies of special prosecutors Melissa Houston and Pat Ryan. The Attorney General’s Office originally provided NonDoc with incorrect totals.)