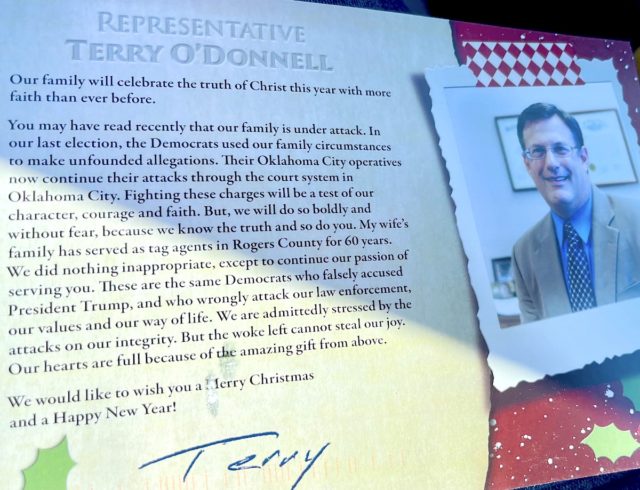

Indicted with his wife Dec. 17 on allegations that he amended a tag agency law for their family’s direct financial benefit, Rep. Terry O’Donnell (R-Catoosa) has blamed his prosecution on “Democrats” and “Oklahoma City operatives.”

“We are admittedly stressed by the attacks on our integrity,” O’Donnell wrote to other lawmakers and state officials in a Christmas mailing. “But the woke left cannot steal our joy.”

Despite his registration as a Democrat, few political observers would call Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater the “woke left.” Prater has handled the ongoing O’Donnell investigation, compelling testimony in front of the state’s multi-county grand jury last spring and calling additional witnesses for his own Oklahoma County grand jury after the MCGJ ended its tumultuous term unspectacularly in September. Prior to being indicted, O’Donnell had no discernible beef with Prater, who has exercised Oklahoma County’s jurisdiction as authority to prosecute corruption cases involving state lawmakers of both parties over the past 16 years.

But O’Donnell did have bad blood with former Attorney General Mike Hunter, who resigned unexpectedly May 26, days after filing for divorce and having an extra-marital affair revealed. In 2019, O’Donnell was one of the most vocal critics of Hunter’s $269.5 million settlement with opioid manufacturer Purdue Pharmaceuticals, which kept the state out of the nation’s larger lawsuit against the company and dedicated 66 percent of settlement dollars to a foundation supporting Oklahoma State University research. (Another 22 percent went to private law firms with which Hunter had contracted on his opioid lawsuits.)

An attorney himself, O’Donnell challenged Hunter’s ethics and said Hunter violated state law by distributing settlement proceeds without input from the Legislature. He had questions about the employment of Hunter’s son at OSU, and he ran a bill strengthening the law he said Hunter had violated.

Beyond his public criticism of Hunter, O’Donnell channeled the Legislature’s frustration over the situation by aggressively questioning Hunter on the topic during a packed March 2019 meeting with Gov. Kevin Stitt and legislative leaders, according to multiple people who were in the room. As others watched the tense exchange between O’Donnell and Hunter, Stitt eventually helped break up the verbal confrontation by saying everyone was on the same team.

‘Hold some very influential people accountable’

Nearly three years later, O’Donnell is the man in the hot seat, defending himself against a slate of criminal charges related to his 2019 tag agent bill that changed a law and allowed his wife, Teresa, to be named successor to her mother as a state Motor License Agent.

Although he did not name Hunter specifically, O’Donnell’s Jan. 6 statement announcing his resignation from a House leadership position appeared to blame his criminal prosecution on the resigned attorney general.

“This all started when I sought to hold some very influential people accountable for gross abuses of power,” O’Donnell said after completing the booking process at an Oklahoma County jail. “This is retribution.”

But Prater told NonDoc that O’Donnell’s implication is false, despite acknowledging that he originally looked into the matter at the request of Hunter, who said he had a “conflict.”

Asked about the potential for O’Donnell to paint his Oklahoma County indictment as a political favor to Hunter, Prater agreed to discuss his communications with Hunter regarding the O’Donnells.

“My involvement in this has nothing to do with politics,” Prater said after his Oklahoma County grand jury held another session last week. “I can’t speak to the beef between Hunter and O’Donnell, but that had nothing to do with me agreeing to look into the matter, and it had nothing to do with the indictment the grand jury ultimately returned against Terry O’Donnell and his wife.”

Prater said Hunter asked him if he had read either of the stories that Nolan Clay of The Oklahoman had written about the Catoosa Tag Agency in September 2020.

“I told him I had vaguely seen it in passing in the paper, didn’t recall reading any of the articles about it and had pretty much dismissed it,” Prater said. “In a conversation about two weeks later, Attorney General Hunter again asked me if I was familiar with what was going on with the Catoosa Tag Agency, and I again told him I wasn’t.”

Prater said “it wasn’t too much longer” before Hunter referenced the issue a third time.

“He said he felt it needed to be investigated and that he had a conflict. Ultimately, he asked me to be assigned to look into the matter, due to the conflict that his office had,” Prater said. “I asked him why I had jurisdiction, and he indicated that it was related to some legislation that had been passed. I said OK, but I still knew very little about what was going on with the Catoosa Tag Agency or what he was referring to.”

Prater said he agreed to take the assignment and lead the investigation because Hunter was disqualifying himself.

“I was not aware at the time I agreed to look into the matter what the conflict was,” Prater said. “I told Hunter that if he felt his office had a conflict that I would not be sharing information with him about the investigation or sharing any grand jury matters with him.”

But Prater did ask Hunter for one form of assistance if he was going to look into the matter at the formal request of the Attorney General’s Office.

“When I agreed to go ahead and look into whatever was going on with the Catoosa Tag Agency, I told Attorney General Hunter that I did not have anyone in my office who had any time at all to assist me in the investigation,” Prater said. “I felt that since he had disqualified out of the investigation, he should provide — or at least pay for — a lawyer to assist in the investigation. And he did so at my request. I requested an individual that I had worked with in the Oklahoma County DA’s Office and who had previously retired from the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office.”

That individual was Charles Rogers, who Prater said was contracted as a part-time assistant attorney general and “was assigned directly to me to conduct the investigation.”

“I instructed him not to — and I am confident that he did not — share information with Attorney General Hunter regarding the matter,” Prater said of Rogers. “We were well into looking into this deal when I learned there was a significant issue between Hunter and O’Donnell. At some point, I was told that there was a significant rift between Hunter and O’Donnell over the use of the opioid settlement money.”

After Hunter resigned in late May, Prater said he was later informed that Rogers’ contract with the Attorney General’s Office to assist Prater would be terminated, despite Prater’s ongoing investigation of the O’Donnells in front of the multi-county grand jury.

For reasons he said were never explained to him, Prater said he was denied the opportunity to call additional witnesses before the multi-county grand jury during its May, July and September sessions. After its September session, the multi-county grand jury concluded its 18-month term and produced a final report, saying it issued 1,313 subpoenas and entertained 160 witness appearances.

Prater said his unfinished investigation into the O’Donnells and the Catoosa Tag Agency helped motivate him to request his own Oklahoma County grand jury in late September. That grand jury was seated in October, and Prater — who had subsequently contracted with Rogers to rejoin his office — began the process of reading multi-county grand jury testimony to the new Oklahoma County grand jury in November.

“Because the legislative action and much of the transfer of (tag agent application) documents to the Tax Commission occurred in Oklahoma County, I had concurrent jurisdiction to investigate it,” Prater said.

Asked if he had additional comment on his indictment, a public relations professional contracted by O’Donnell referred NonDoc to the lawmaker’s prior remarks.

Hunter criticized for separate investigation

Although O’Donnell may be able to say Prater was asked to investigate him by a political nemesis, casting doubt on the underlying theory of the crime will be a tougher task.

O’Donnell can be seen on video presenting HB 2098, which changed a law in a way that directly allowed his wife to be appointed tag agent by the Oklahoma Tax Commission. Records show that O’Donnell communicated with OTC staff regarding his wife’s formal application, which he submitted to the agency himself. One month after O’Donnell’s bill became law, his wife was named tag agent.

In late December, both Stitt and Senate Appropriations Chairman Roger Thompson (R-Okemah) confirmed to NonDoc that O’Donnell’s bill had been communicated to them as a “House priority” in 2019. Stitt declined to say whether he had initially threatened to veto O’Donnell’s bill, and neither he nor Thompson elaborated on what leverage may have been used to push the bill through the legislative process. Those questions may be part of Prater’s ongoing investigation.

Regardless, the heft of the grand jury indictment against O’Donnell dwarfs the testimony heard by the multi-county grand jury for the signature corruption indictment of Mike Hunter’s attorney general tenure: a since-dismissed attempted bribery charge against then-Stitt cabinet secretary David Ostrowe.

For starters, Prater’s investigation of O’Donnell has featured at least 27 “fact witnesses” who testified before the multi-county grand jury and then the Oklahoma County grand jury about things they knew or observed. The Ostrowe indictment, achieved by Hunter’s Multi-County Grand Jury Unit, came after the testimony of only one person: Thomas Helm, an Attorney General’s Office senior investigator.

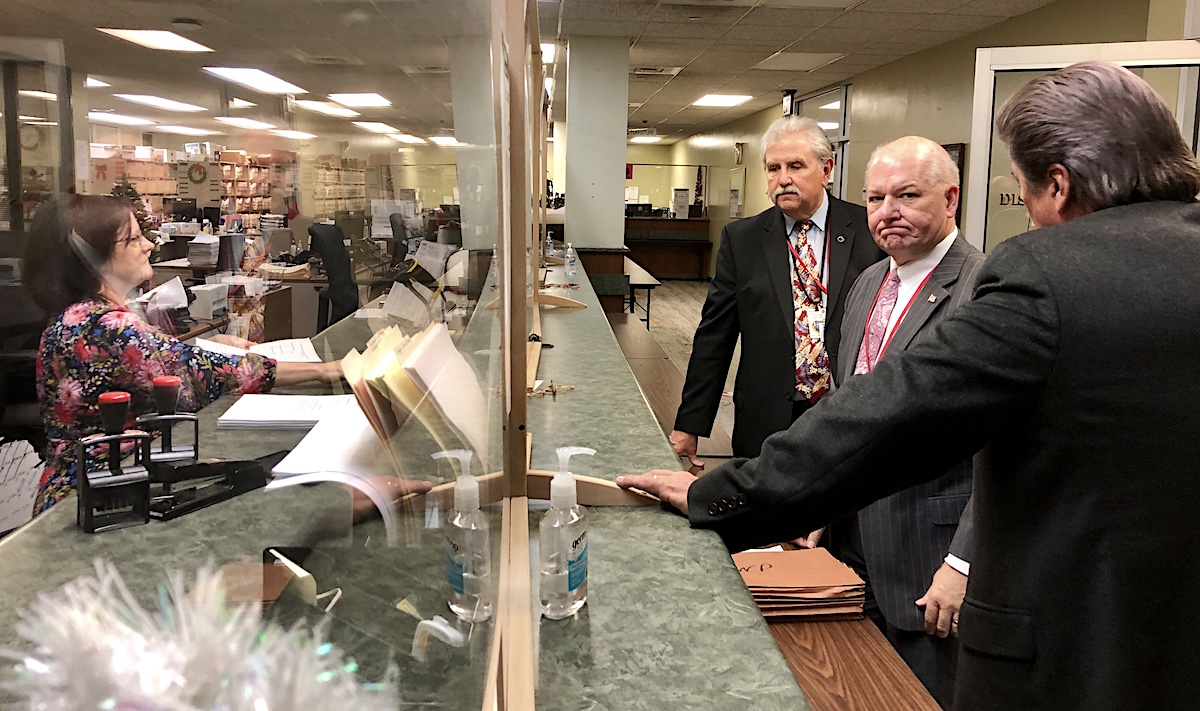

For his indictment of the O’Donnells, Prater hauled several state employees, three current and former tax commissioners, two former Tax Commission directors and House Speaker Charles McCall — one of O’Donnell’s closest friends in the Legislature — in front of the grand juries.

But to achieve the Ostrowe indictment, Joy Thorp, who still leads the AG Office’s Multi-County Grand Jury Unit after Hunter’s resignation, presented the MCGJ with only two rounds of testimony from Helm, an investigator for the AG’s Office.

Helm and Thorp jointly conducted interviews with tax commissioners, but Thorp called only Helm to testify about their interviews in the Ostrowe investigation. While current and former Tax Commissioners Steve Burrage, Charlie Prater and Clark Jolley — as well as Thompson, the Senate appropriations chairman, and former Sen. Jason Smalley — were the actual witnesses interviewed by Helm and Thorp for the Ostrowe investigation, none of them were called to testify before the multi-county grand jury.

Asked if Helm, Thorp or anyone with the Attorney General’s Office could comment about why Helm was the only witness called before the multi-county grand jury, Madelyn Sheriff said there was nothing unusual about the Ostrowe investigation.

“The process undertaken was identical to every other case brought before the grand jury,” said Sheriff, who serves as press secretary for new Attorney General John O’Connor.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Hunter, AG’s Office and others sent tort notice

Other key differences exist between the O’Donnell and Ostrowe investigations as well. Notably, Prater has emphasized that his investigation of O’Donnell and related elements of the 2019 legislative session remains active before his Oklahoma County grand jury.

But when he resigned as attorney general, Hunter quietly dismissed the multi-county grand jury’s indictment of Ostrowe, who has publicly criticized Hunter and has alleged that he “weaponized” the state’s top law enforcement office by conducting “outcome oriented” investigations.

Ostrowe made that allegation in a Dec. 9 notice of tort claim sent by his attorney, Matt Felty, to O’Connor, his office, the Oklahoma Tax Commission, Tax Commissioner Charlie Prater and Hunter’s attorneys. (Hunter is represented by Mike Turpen and Robert Nance of the Riggs Abney law firm. Charlie Prater and David Prater are not related.)

Ostrowe subsequently sued the Oklahoma Tax Commission on Dec. 27 over the preservation and provision of documents and communications regarding Ostrowe. In November, the OTC had denied Ostrowe’s open records request as “overly broad.”

In Felty’s Dec. 9 tort notice on Ostrowe’s behalf, he wrote:

By maliciously prosecuting Mr. Ostrowe, Hunter knowingly broke the oath he took to the state of Oklahoma and, in turn, the trust of the citizens of Oklahoma. Rather than let evidence and truth be the guideposts for criminal prosecutions, Hunter weaponized the AG Office for self-advancement no matter the cost. In the case of Mr. Ostrowe, Hunter started with the premise that someone close to Gov. J. Kevin Stitt (…), with whom Hunter had heated conflicts on a number of notable issues including renewal of the tribal gaming compacts as well as the opioid litigation, needed to be indicted. From there, Hunter and his cronies worked backwards to find a reason for an indictment, no matter how pretextual or contrived the underlying allegations turned out to be.

Asked about Ostrowe’s allegations that Hunter had “weaponized” the Attorney General’s Office to investigate political rivals, Prater emphasized that he never discussed his investigation of the O’Donnells with Hunter after agreeing to the assignment.

“I stand by the grand jury’s work. I stand by the indictment, and the evidence that will be made public at the appropriate time regarding the matter and regarding the information that led to the indictment,” Prater said of the O’Donnells. “People will have an opportunity to determine for themselves if it was based on the evidence or whether they think it was political, but I will tell you there was nothing political about this investigation or the indictment.”

Hunter did not return a phone call seeking comment prior to the publication of this story.