The website of the downtown Oklahoma City restaurant Ludivine currently sports a banner proclaiming, “We are hiring!” Like many businesses in the food-service industry, Ludivine was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, and now, as more people are venturing out, packing the city’s eateries on any given weekend night, the restaurant has found itself short-staffed.

“By the time we had been back open for a few months, I didn’t have anyone on staff that I had on staff before the pandemic,” said Andy Bowen, Ludivine’s general manager. “I think the last pre-pandemic staff member I lost was our bartender, and she was really a jack of all trades, and really great person above all.”

That former staffer is still in the food service industry, but has shifted gears.

“She’s decided to focus on the culinary side instead of the service side,” Bowen said.

As a result, Bowen has been left to search for people to replace her and other departed employees. Line cooks and sous chefs are in particularly short supply.

Businesses around the country report similar staffing challenges, but the cause of these challenges is not immediately clear.

Republicans largely say it’s time to cut off $300 in weekly enhanced federal unemployment benefits for those still not working. And indeed, some states, including Oklahoma, have done that.

“The federal government has created an incentive to stay at home instead of getting back into the work force,” Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt said in May as he announced plans to end the enhanced benefits and to offer $1,200 stipends, among other incentives, to unemployed Oklahomans who returned to work.

Democrats, meanwhile, largely believe the imagery of Americans sitting around doing nothing is a myth and that staffing shortages are caused by other factors.

“It’s not that people aren’t working, its that’s they have found better jobs and better opportunities for themselves and families,” Rep. Mickey Dollens (D-OKC) said in response to Stitt’s decision.

Not long ago, it was unclear how the country would cope with widespread unemployment caused by the spread of COVID-19. Now, as Americans emerge from the pandemic’s worst days, a heavily politicized debate has broken out over how to fill open jobs and whether the apparent labor shortage even exists.

Some industries facing labor shortages, leaders say

State Chamber of Oklahoma President Chad Warmington said employers he’s spoken with in Oklahoma have had trouble recruiting and hiring staff in recent months.

“It’s been interesting. Nearly every employer in our membership has said they have had trouble filling positions,” Warmington said. “It’s a struggle across a variety of industries. Some of the reason that is happening, they were told, is because the federal unemployment benefit makes it easier not to work. We clearly saw the need for those benefits during the heart of the pandemic, but that need has pretty clearly expired.”

Warmington said steps like Stitt’s stipend plan, which included subsidies for people needing childcare during a job interview, can be effective.

“Having that ability to go out on job interviews without worrying about how you can pay for childcare is another great benefit that kicks down a barrier,” Warmington said. “I believe it was smart of Gov. Stitt to offer those kinds of incentives.”

‘It’s been heavily politicized’

University of Central Oklahoma economics professor Travis Roach has read and seen news reports about labor shortages across the United States in recent weeks, and he doesn’t completely buy it.

“It has been heavily politicized,” Roach said of the discussion about labor shortages. “I think what we’ve seen is policy makers who have used anecdotes rather than data when it comes to making their arguments.”

Roach said the number of people receiving unemployment benefits continues to decline weekly, which undercuts the argument people are lying around waiting for a check.

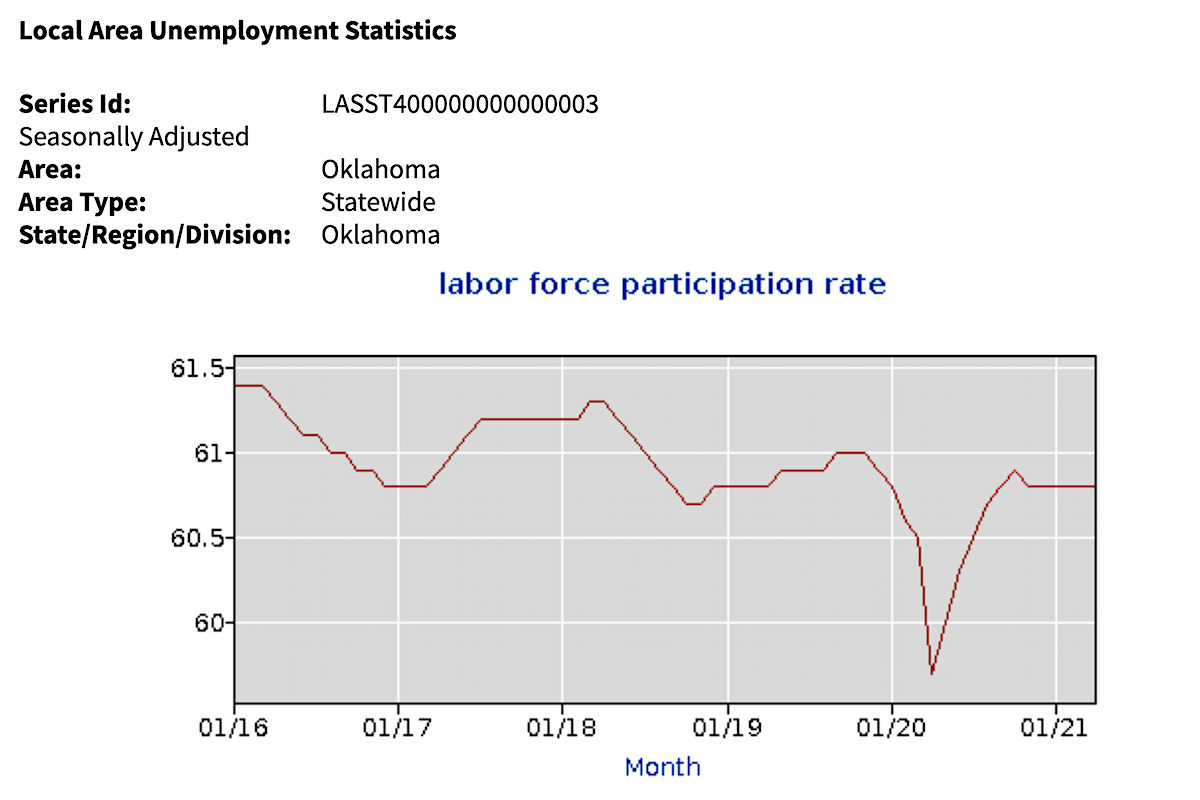

“There are people who are just now getting past their second shot and for the first time in a while have felt comfortable being among other people, which is part of it,” Roach said. “But the reality is, labor force participation is basically back to what it was in 2019.”

The numbers are close. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the labor participation rate was 63.3 percent in December 2019. As of May 2021, it stands at 61.6. The rate dipped to a pandemic-low 60.2 percent in April 2020.

Oklahoma’s unemployment rate is 4.3 percent as of May. In December 2019, it was 3 percent.

‘I couldn’t blame anyone who chose to leave the industry’

Where some see a labor shortage, others see a change in direction as people choose to leave service jobs.

Ludivine, a farm-to-table restaurant that serves up such dishes as bone marrow starters and glazed bison oxtail, got through the pandemic with a skeleton staff, filling curbside and delivery orders. The restaurant received federal Paycheck Protection Program money and furloughed most of its employees with pay. But over the ensuing months, the restaurant saw a near 100 percent turnover as staff left for other opportunities.

Bowen said he has remained in his job and in the food industry because he loves the work.

“At our best, all of us really just like getting to know people, and this business gives us an excellent opportunity to get to know people,” he said. “I didn’t really need a big shakeup in my life, because I didn’t dread coming to work every day.”

But he acknowledges that others may not feel the same way, especially when working in a restaurant during a pandemic also came with an elevated risk of contracting the virus. Since many in the industry don’t have employer-provided health care, a serious illness could be devastating financially.

“It’s difficult to watch millions of people get sick and die, and millions more have their lives permanently and irrevocably altered with long-term health conditions, without thinking, ‘Am I spending my time and my health the way I want to be, or should be? In a way that I won’t regret when I don’t have that health anymore?'” Bowen said. “It certainly did that for me. I chose not to leave Ludivine. I chose to bring that energy to Ludivine. But I certainly couldn’t blame anyone who chose to leave the service industry.”

Bowen says he believes the difficulties he has faced finding staff are largely due to problems in the industry.

“It’s not bad at all if you pay people,” he said. “The fact of the matter is, in this industry, we’ve been wildly, obscenely under paying people for decades, and we don’t get to do that anymore. And, frankly, thank God. This reset has been needed for a very long time.”

Restaurant pay disparities between front-house staff and kitchen employees have also been an industry issue for years.

“If this is a labor shortage or whatever it is, it’s because these workers have deserved more for a long time,” Bowen said. “I disagree vehemently with the idea of penalizing people for not going back to work. Some people have very good reasons for not re-entering the workforce yet, and some people have re-entered, just not in the ways the state wishes they would.”

Bowen said many of his staff have left to pursue opportunities in the state’s medical marijuana industry. One left to become a dental technician. Another is working on a graduate degree.

“The marijuana industry is one attracting them more than any other, I think,” Bowen said. “They go to the dispensaries or grows. A lot of these people are very talented, intelligent people. They’re not necessarily taking another hourly wage job. Some of them are trying to get into the ground floor of it the best they can.”

For David Attalla, who is managing partner of Wedge Pizza, Drum Room and the Blue Note Lounge in Oklahoma City, the pandemic provided an opening for a career shift. He is still involved in those businesses and the food service industry, but he has handed off much of the day-to-day operations and now works as a sales rep for a food-service company that supplies restaurants in central Oklahoma.

“It’s been a change of direction for me,” Attalla said. “I never worked for anyone in my life. I’ve always been my own boss. But I’ve jumped in the middle of it. I like the structure.”

And he also sees how much time he gave up to be in the business.

“The pandemic has been a really terrible thing that, ironically, has sort of led me in a different direction that has changed my life for the better,” he said. “I think for me, what I want, is job security and the ability to control my own destiny. Nights and weekends were never good for my family life, either.”

‘A kick in the ass’

How the job market shakes out remains to be seen as America exits the worst stages of the pandemic. Airports are as full as they’ve been in more than a year, and restaurants are increasingly busy. Even the moribund brick and mortar retail shopping sector is holding its own, with industry leaders forecasting as much as $4.5 trillion in sales this year, an increase of more than $500 billion over 2020.

In short, there are jobs out there, but not everyone wants them.

“It shows up in the data,” Roach said when asked if people are simply reevaluating and changing career paths. “In a lot of industries, risk is rewarded with high pay. That’s not true for some jobs, though. Restaurants and grocery stores come to mind. Childcare. They’ve all had some difficulty finding workers that are experienced.”

Roach said UCO’s MBA program has been enrolling many students who are looking to change gears in their careers.

“We have definitely seen a lot of re-skilling in the graduate programs,” Roach said. “They want to get into a new sector and don’t like the long-term prospects of what they were doing before. We’ve seen students who have come from the oil and gas industry that don’t really want to do that anymore because of the volatility.”

Warmington said even though there are shortages in some industries, people taking the time to make sure they are in an industry that meets their needs isn’t necessarily a bad thing, either.

“There’s been a lot of people who have taken this opportunity to be a little bit more selective in picking the job they want,” he said. “I think that’s a good thing. In some ways, workers are more empowered now to get a job that’s better suited to them. And I think we’ve seen some wage increases out of it. But still, I don’t think having the extra federal benefits would have been a good thing for Oklahoma in the long term.”

What is good, though, is reflection. Bowen sums it up this way.

“Hey, maybe there’s someone who has been a trim carpenter for 25 years, and they’re really good at it,” he said. “But it’s nothing that particularly excited them. Maybe what they want to be doing is serving wine to people. I think the pandemic has given a lot of people a kick in the ass to do what they want to do.”

(Editor’s note: The State Chamber of Oklahoma has been a financial sponsor of the Sustainable Journalism Foundation’s public debate series since 2020.)