In October, the U.S. Department of Education released The Nation’s Report Card based on fourth- and eighth-grade students’ 2022 scores on reading and math tests that had been administered for the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. While most states saw declines in scores compared to 2019, Oklahoma’s report card reflected even further deviations below the national average.

Ryan Walters, then still two weeks away from winning election for state superintendent of public instruction at the time, seized on the results immediately, criticizing then-current State Superintendent Joy Hofmeister for supporting the pandemic lockdowns and virtual-learning models many districts had adopted in 2020 and 2021 as an effort to avoid spreading the virus.

“The recent test scores are a clear sign that nothing can replace in-classroom learning,” Walters said in a tweet. “It is disappointing that in the rush to respond to a crisis our kids suffered the most. We must do better for parents, teachers, and kids.”

The report card results reflect what superintendents and teachers across the nation already knew: The pandemic, with the lockdowns, virtual learning and added stress that came with it, hurt students. While some have used that fact as political fodder to cast blame on officials who made decisions trying to keep people safe from the virus, others have acknowledged the necessity of virtual learning along with its downsides.

John Cox, superintendent of Peggs Public School and a 2022 Republican primary candidate for state superintendent, said his students’ clearly experienced “learning loss” from the pandemic.

“I think we did lose a complete year through virtual (learning),” Cox said.

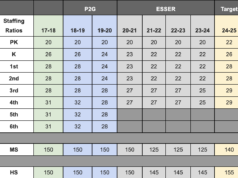

Oklahoma eighth-grade proficiency

2019 reading: 26%

2022 reading: 21%2019 math: 26%

2022 math: 16%Oklahoma fourth-grade proficiency

2019 reading: 29%

2022 reading: 24%2019 math: 35%

2022 math: 27%(Source: NAEP)

The U.S. Department of Education uses the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests to create the federal report card.

In 2022, just 21 percent of Oklahoma eighth graders scored at or above proficient on the reading part of the NAEP exams, down five points from 2019 when 26 percent of Oklahoma eighth graders scored at or above proficient. (Nationally, 29 percent of eighth graders scored at or above proficient in 2022.)

In math, only 16 percent of Oklahoma eighth grade students scored proficient or higher last year, down 10 points from 2019 when 26 percent scored proficient.

Fourth-grade students in Oklahoma showed a similar decline for both subjects. In reading, 24 percent of students scored proficient in 2022, compared to 29 percent in 2019 (and 30 percent in 1998). Nationally, 32 percent of fourth-grade students scored proficient or higher in reading last year.

In math, 27 percent of Oklahoma fourth graders achieved proficiency last year, another sharp decline. In 2019, 35 percent of Oklahoma fourth-graders scored proficient or higher (more than double the 16 percent who did so in 2000).

“We’ve just made a point to say that we’re going to work our way through it,” Cox said. “Even though our team did an admirable job, putting everything online, working with their kids, trying to corral them to be on their iPads — they did an outstanding job doing that. It just wasn’t good for our children.”

Virtual learning: ‘An admirable job on coping’

Cox, who has led his rural Cherokee County school district for more than 25 years, said that while some of the nearly 200 students in Peggs’ pre-kindergarten-through-eighth-grade school handled the shift to online learning with few issues, others did not.

“I think there’s a niche for maybe 3 to 5 percent of our kids that can be virtual and be responsible and have those characteristics that can make them be successful,” Cox said. “I think every child needs consistency.”

For Cox and his teachers in Peggs, an unincorporated community east of Tulsa and 16 miles northwest of Tahlequah, recovering from the pandemic has involved synthesizing lessons learned over the past three years with new trainings and tools.

“My teachers and staff up here just did an admirable job on coping with things and coming out of it,” Cox said. “And I think it’s made them stronger.”

One of the new training programs some Peggs teachers attended involved learning to implement the Science of Reading, a reading curriculum that focuses on teaching students to decode words by studying each letter and the sound it makes within the word.

Walters, who has pushed the Science of Reading heavily during his short time in office, is scheduled to make a budget request of the Oklahoma Legislature this week that would include $100 million to create a robust statewide literacy system focused on the Science of Reading. Calling his proposal “bold” and “aggressive,” Walters said his goal is to drastically increase student literacy as soon as possible.

While lawmakers do not have to act on Walters’ budget request, he has been insistent that the state needs a comprehensive reading program, such as the one he is proposing. Cox, who also praised the Science of Reading curriculum, said such programs are often easier to introduce in smaller districts.

“(Larger districts are) like a gigantic yacht that you’re having to turn around — or a cruise ship,” Cox said. “And here, we’re more like a speedboat. So, we can make adjustments to what we do.”

Other superintendents across the state say their districts have also faced pandemic learning loss.

Bartlesville Public Schools Superintendent Chuck McCauley called his district’s recovery a “challenge” and said the 2022-2023 school year actually felt like the first year of improvement for his students and teachers.

“They were better,” McCauley said of BPS’ 2022 test scores. “They weren’t where they were before the pandemic. We still have much work to do. (…) So really, what we’re seeing is a start. And I think it’s gonna take some time to fill in.”

Talihina, a rural community of just under 1,000 people near the Arkansas border in the Choctaw Nation, has a public school district serving 511 students. Its superintendent, Jason Lockhart, also said the pandemic hurt students’ learning.

“Kids definitely fell behind when we went through that shutdown in March (2020),” Lockhart said. “I am not, I mean in no way, saying that somebody made an irresponsible decision because the whole world didn’t know what was going on. But the ultimate end of that, there was some learning loss that took place there.”

Two hours north of Talihina and an hour east of Peggs in the Cherokee Nation, Westville Public Schools Superintendent Terry Heustis said that in addition to pandemic learning loss in his district, students’ behavioral problems have been exacerbated over the past three years.

“What I’ve seen more than the math and the reading is behavior,” Heustis said. “That period of time in their life is very important — that fifth-, sixth-, seventh-grade year — for emotional development. And so, it’s really pushed them back.”

Though it is clear that many of the pandemic’s problems are universal across school districts, some have differed in how they define and approach the issues.

Assistant Superintendent of Elementary Schools Jamie Polk in Oklahoma City Public Schools does not call her students’ declining test scores “learning loss.”

“In regards of ‘learning loss,’ I’ve kind of got my own little personal philosophy about that term because in order to lose something, you have to have had it,” Polk said. “So, I don’t necessarily see our students as having a learning loss, but their learning trajectories have changed.”

Rather than working to get students caught up, OKCPS is simply trying to meet students where they are, Polk said.

“What’s most important is they should be guaranteed at least nine months’ worth of growth from where they are,” Polk said. “For us, as an urban public [school district], we just take the kiddos where they are, and then each child then gets that opportunity for growth of at least nine months. And so that’s how we kind of determine how we’re moving from that point on.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Teacher shortage exacerbates pandemic learning loss

Despite districts’ varying ways of addressing their students’ learning needs as they try to recover from the pandemic, another factor remains a constant problem: the teacher shortage.

While Oklahoma districts were already suffering from a lack of qualified teacher applicants before the pandemic owing to a multitude of factors, there is little doubt that the extra stress, health risks and professional responsibilities that came with the pandemic exacerbated the issue.

Additionally, many districts — such as Bartlesville — are facing a shortage of other employees.

“This last year, what really hit us was the support staff — our hourly positions like teacher’s assistants, special ed professionals, bus drivers, those types of positions,” McCauley said.

As lawmakers and officials in the Oklahoma State Department of Education debate how best to fix the issue, districts across the state have had to get creative in an effort to stem the outward flow of employees. Districts’ solutions have ranged from giving spa days to burned out teachers to making financial decisions aimed at supporting employees.

Another seemingly counterintuitive but common experience from the pandemic is that districts saw some financial and infrastructure benefits. Districts that did not already have robust technology adoption were forced to do so quickly, and they were aided by millions of federal dollars appropriated to help schools navigate challenges.

“I think in the long run, the pandemic is gonna help a lot of things, but it was terrible,” Cox said.

With federal CARES Act money, Peggs was able to bring internet to more Cherokee County homes to help students learn virtually.

Bartlesville’s efforts to recruit staff and students in the wake of the pandemic actually led to new growth in the district.

“So, we just need to continue to invest in resources. We doubled the size of our elementary and secondary summer schools, in terms of enrollment and staffing enrollment. (We need) to get just that additional support,” McCauley said. “There’s been lots of challenges that have come up, and I really think it’s gonna take years to kind of fill those to meet those needs.”

As districts continue to work toward recovery efforts, many have realized that the pandemic’s lasting marks will not go away any time soon.

Peggs, for instance, saw a teacher die after contracting COVID-19, which Cox said was “devastating” for the school.

“I bring her up because I think it’s important to remember what we went through and the devastating effect that it had,” Cox said. “It impacted not just learning but just who we are.”