It did not have to be this way for the Big 12 conference.

Last week, conference realignment hit college football again with warp speed. In a matter of four working days, a storyline metamorphosized from the University of Oklahoma and the University of Texas possibly leaving the Big 12 Conference to their official intention to bolt being announced by letters from both schools.

Now, the SEC has offered the two schools a formal invitation, and both the OU Board of Regents and the University of Texas System Board of Regents have voted to leave the Big 12 for the SEC in 2025. The future of the Big 12 looks murky at best.

If not for a lack of resolve, foresight, initiative and self-awareness, this all could have been avoided.

A successful shotgun marriage

Formed in 1994 from a combination of the Big Eight and four Southwest Conference teams, the Big 12 played its first season in 1996. Many viewed the new conference as the Big Eight rescuing four Texas-based schools. Some, though, saw the circumstances through a different lens of the SWC saving the Big Eight.

Considering all Big Eight schools joined, but only half of the Southwest Conference members did, that felt like an odd, Monty Python’s Black Knight-type viewpoint (Tis but a scratch!), but one that previewed how the league would be far from a true partnership and more of a shotgun marriage.

Still, the league thrived in its opening years. Nebraska grabbed a football national title in 1997, the Sooners did so in 2000, and Texas won a ring in 2005. Besides those three titles, a Big 12 team also played in the national championship game in 2001, 2003, 2004, 2008 and 2009. It could be argued that the Big 12 was the premier college football conference in the country during its first 14 years of existence.

Cracks appear

Entering the new decade in 2010, however, the shotgun marriage had begun to sour. Nebraska suddenly wearied of dealing with Texas and bailed for the Big 10 Conference. Colorado found itself without its top rival in the conference, so the Buffs left for the Pac 10 (soon to be Pac-12) Conference.

A year later, citing a similar reason of being tired of the Longhorns, Texas A&M left for the Southeastern Conference and carried Missouri along for the ride.

Why did the Cornhuskers and Aggies leave? I suppose we could believe they were simply sick of working with the Longhorns. Surely nothing had to do with the fact Nebraska was 0-5 against Texas while posting a relatively pedestrian 63-40 overall record from 2002 through 2009, or that Texas A&M was 48-50 overall and 2-6 against the Longhorns in the same period.

If either program would have had more success on the field, or a stouter chin during the down years, would the original Big 12 membership remain today?

Saved, but stagnant

The Big 12 Conference stuck together despite the defections. In 2012, Texas Christian University and West Virginia University were added as solid — if not completely adequate — replacements. And despite the dissociative nature of its name, the Big 12 continued on with 10 teams.

RELATED

All aboard: Regents vote for OU to join the SEC in 2025 by Tres Savage

And on … and on … and on.

For nearly a decade, the Big 12 Conference showed no foresight, no ambition, no initiative and no creativity — at least not publicly. In 2010, there was noise that Florida State and Clemson were unhappy with the upcoming TV contract for their Atlantic Coast Conference. The Big 12 was rumored to be discussing expansion at the time, but nothing came of it involving the ACC schools. Were there conversations behind the scenes that never became public? Possibly, but even that would mean Big 12 leadership missed an opportunity to appear proactive to the fanbases and administrators of existing schools.

In 2014, Louisville joined the ACC. At the time, it was generally considered a nice, if somewhat inconsequential move in the landscape of college athletics. The Cardinals would bring a staunch men’s basketball program and little else to the table for the ACC. It only took a few years, however, for Louisville to take advantage of their newfound major conference windfall and flex their muscles in football, baseball and women’s basketball, and become one of the jewel acquisitions of the realignment process.

The Big 12 had a chance to bring Louisville into its stable when West Virginia and TCU joined in 2012, as well as the immediate years that followed, but the Big 12 reportedly passed.

The lesson wasn’t learned in 2016 when the Big 12 literally began accepting applications from teams in mid-major conferences. Spurred by OU President David Boren’s quip of the conference being “psychologically disadvantaged” with just 10 members, it turned out to be kabuki theater. Conference leadership decided not to expand, as it was deemed no applicant would immediately bring more money in a TV contract.

Of course, with just a little foresight, it would have been easy to import a Houston, Cincinnati or Memphis and give them a chance to flourish like Louisville in a new major conference environment. The current Big 12 teams could have sacrificed a little money early for the chance of more in the future, along with increased stability.

Houston is the eighth largest TV market in the nation. Cincinnati is 37th largest (six spots ahead of Oklahoma City and three ahead of Austin, Texas). Memphis is a respectable 51st. How bad could adding those markets have been in the long run?

Turning a blind eye

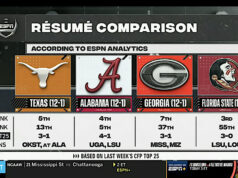

So, the Big 12 Conference lurched onward. In fact, from 2015 to the present, it was even praised in some corners of the sportswriting world as being successful. Conference teams had made the CFB Playoffs four of the six years, and the TV payout had managed to increase to a range of $35 million per team.

The problem was, some people failed to notice two things. First, the only school making those football playoff appearances was the University of Oklahoma, and OU and Texas made up an incredibly high majority of showcase games for the conference’s TV partners. Like living, breathing examples of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, the Big 12 leadership and members patted themselves on the back for their good work and excellent success.

Besides the lack of self-awareness, the conference continued to show a stunning absence of foresight. During the last half-decade, the Pac-12 Conference wobbled. With a mediocre TV deal and similar results on the playing field, the West Coast collection of teams appeared vulnerable.

Again, there is no telling if one of the Pac 12’s teams might have changed conferences, but the effort to talk to Arizona and Arizona State about joining the Big 12 would have been minimal and, again, would have showed current members that the Big 12 was being visionary and proactive.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

End of the road

Instead of being visionary and proactive, however, the league continued to draw strange lines in the sand. Issues arose, such as not working with Oklahoma on better kickoff times for games, and the sudden over-officiating of the “Horns Down” hand signal, which OU players and fans have been flashing their rivals for the better part of five decades.

In all, the Big 12 Conference showed for years that it was reactive, at best, to the business of college football. Too many storylines about hand gestures instead of grand gestures seemed to grease the gears for the Sooners and Longhorns to finally call it quits.

It’s hard to blame OU and Texas for not wanting to simply stay together for the kids, as the old Blink 182 song begs. Those in charge of the Sooners and the Longhorns athletic programs finally tired of being the bell cows in a conference that never seemed to try hard enough.

Still, it did not have to be this way for the Big 12.