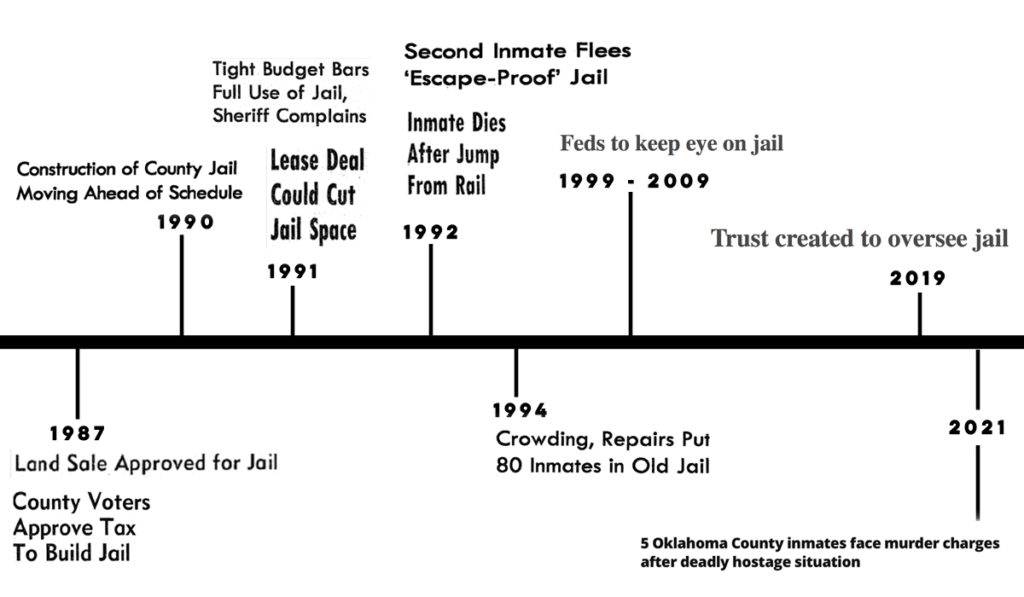

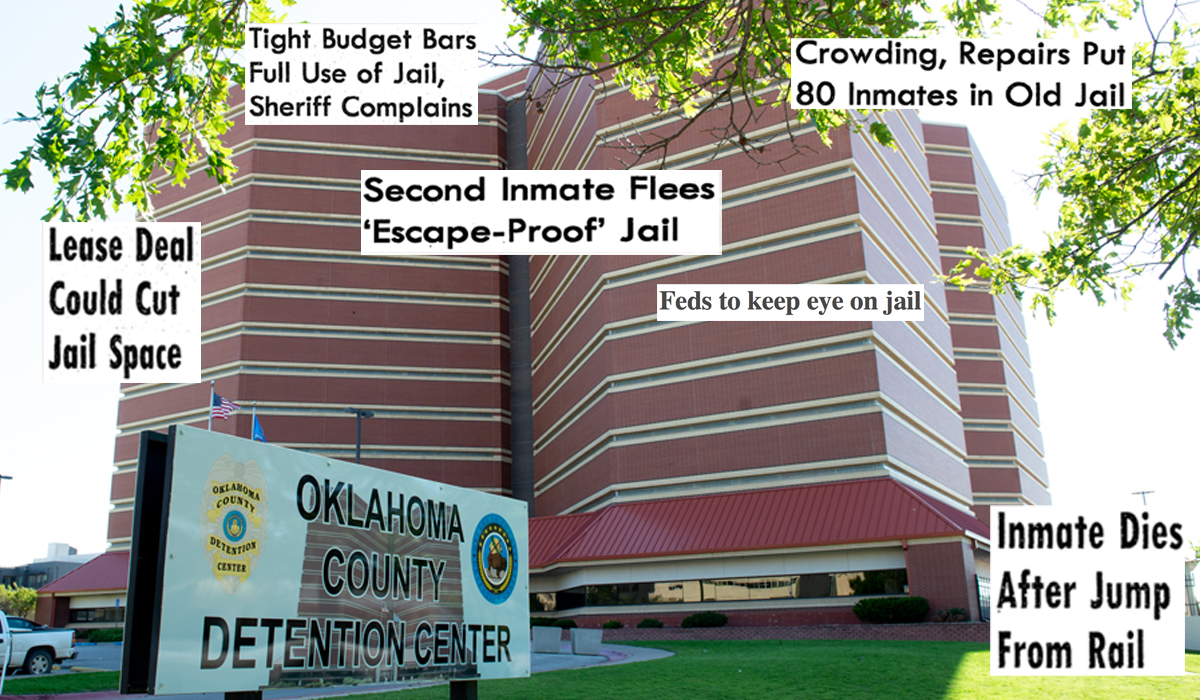

The Oklahoma County Jail has been a source of endless headaches for county officials and residents alike even before the current 13-story tower in downtown OKC existed.

A headline in the August 1965 edition of The Daily Oklahoman featured the headline, “Turner denies his jail’s ‘deplorable'” after the Oklahoma County Jail population, then housed in the top three floors of the County Courthouse, swelled to more than 350 in a space designed for 100 and concerns were raised about sanitation and overcrowding.

Decades later, the conversation is much the same.

The present facility at 201 N. Shartel Ave. has been in use since 1991, but it is plagued by many of the same problems as its predecessor. The facility has been under federal oversight since 2009 and is known more for deaths, bad plumbing and escapes than for safe and successful outcomes.

As was the case in 1965, Oklahoma County is once again grappling with what to do about its troublesome jail. Some argue the county needs to build a new facility. Others say it would be sufficient to build an annex that would remove some critical functions from the tower and streamline the booking process. And, finally, there are some who believe the current structure is salvageable with extensive renovations.

The Oklahoma County Criminal Justice Authority — which has overseen the jail since last year as is commonly called the “jail trust” — recently hired FSB, an Oklahoma City-based architectural firm to study the present jail and those options. FSB’s report is due to be presented this fall and could shape the future of Oklahoma County’s jail.

‘If you lock them up, we’ll build you a jail’

In 1987, voters approved a temporary one-cent sales tax to fund construction of a new $43 million jail. The measure passed with 80 percent of the vote.

The result may have been a reflection of the times. The late 1980s began a “tough on crime” era in the United States that played out culturally and politically. For instance, the 1988 presidential election was arguably swayed by an ad featuring Willie Horton, a prisoner furloughed by 1988 Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis and who later committed a murder while on release. Congress passed new anti-crime legislation in 1991 and 1994.

“If you lock them up, we’ll build you a jail,” then Oklahoma County District Attorney Bob Macy said on election night after the jail measure passed.

Oklahoma County Sheriff J.D. Sharp, who would later engage in a public spat with Oklahoma City Police Chief David McBride over the city’s contract with the jail, said it was a pivotal moment for the county.

“I think for the first time in 10 years we’re going to control the criminal instead of him controlling us,” Sharp said.

Sharp’s words turned out to be ironic after the new jail opened in November 1991. Just two months later, it had its first escape when a detainee punched out some glass bricks and tied bedsheets together to repel from the fourth floor.

Just six days later, another inmate escaped from the second floor in the same manner. Sharp was so exasperated that he threatened to move half the inmates back to the old jail.

“I didn’t need an escape from my supposedly inescapable jail,” Sharp told The Daily Oklahoman after the second escape.

In March 1992, a 33-year-old woman dove head first off the railing outside her cell into the common area one story below. She later died at a hospital, making her perhaps the first person to die in the facility. Many more have followed, including nine so far this year.

In 1993, the county sued Manhattan Construction because of problems with windows it installed, enabling the first two escape attempts.

In 1995, Macy launched a grand jury probe into the jail and its construction woes. The following year, more than $20,000 was spent to fix rubber flaps on toilets that were installed incorrectly.

By the turn of the century, the FBI began looking into conditions at the jail, which had more than 2,200 inmates stuffed inside, although the facility had been designed to hold half that many.

Why a tower?

One reason behind the jail’s woes is its tower design, which also distinguishes it from other facilities in Oklahoma.

Tulsa County’s two-story David L. Moss Criminal Justice Center, for instance, opened in 1997 with a capacity for about 1,700 people. In 2017, the addition of a mental health unit and two open-air-style dormitories brought that capacity to just above 2,000.

The new version of the Cleveland County Detention Center in Norman opened in 2012 and is similar to Tulsa’s in design, with just two stories.

Oklahoma County Criminal Justice Advisory Council director Timothy Tardibono does not know exactly why Oklahoma County chose to build a tower.

“I remember being a college student, and really my first interaction with the jail was seeing a helicopter circling overhead because someone had escaped,” said Tardibono, who went to high school in Putnam City and later attended college at Oklahoma Christian. “They were able to poke holes through the walls. We’re still struggling with that.”

Tardibono said he has heard stories about the reasoning behind the jail design.

“What I’ve always been told was that the high-rise example was something Las Vegas had done, and they built theirs as a high rise and that was the hot thing at the time,” he said. “County officials went out there and saw it and brought the idea back.”

Council on Law Enforcement Education and Training director Brandon Clabes, who served as Midwest City’s police chief for more than two decades, said he doesn’t know either.

“What I remembered is that they wanted to build it downtown because of court, which makes sense, but I’m not sure why the tower design was used other than because maybe it had a smaller footprint,” Clabes said.

Problems with tower designs

Engineer John Semtner works for FSB, the firm contracted by CJAC to study options for what the jail might look like in the future.

He said it’s not surprising the jail’s 30 year history has been so troubled.

“Any high-rise building adds additional challenges to the design and construction,” Semtner said. “And it also adds to the maintenance requirements.”

Tardibono said that comes into play any time one of the jail’s elevators stops working.

“One of the biggest inherent problems with it is you have three elevators, and any time one of them breaks down, things sort of start to break down with operations,” he said. “The other thing that nobody anticipated back then was 2,400 and sometimes 2,800 people in a facility built for 1,200, which added a lot of extra wear and tear, and previous sheriffs’ maintenance budgets didn’t keep up.”

Semtner also sees a problem with the general feel of the current jail and says it might feed others issues.

“I don’t see the maintenance as the only problem with a tower,” he said. “The dreariness of it, the lack of recreation space and sunlight — high rises also need significantly more staff than a low rise. It takes time to move inmates around, and that exacerbates existing staffing challenges.”

Semtner said Tulsa County’s jail allows for better supervision of detainees.

“A lot of people look at Tulsa’s as a model,” he said. “Currently, we have indirect supervision in our jail, where guards aren’t engaging with inmates. Tulsa has a different system where guards and inmates share spaces. That allows for better camaraderie and promotes a better understanding of what’s going on with the population.”

Oklahoma Criminal Justice Authority trustee Sue Ann Arnall said Tulsa’s booking process is more efficient than Oklahoma County’s.

“It’s not as traumatic,” she said. “It’s almost like a doctor’s office.”

That’s not true at Oklahoma County, she said.

“The [district attorney] has agreed to diversion programs, but we don’t have any room, which is part and parcel to how inefficient the booking process is right now,” she said. “It’s mind boggling how [incoming detainees] go from station to station. It takes hours, and it’s inefficient.”

The three options

FSB is examining three options for the jail: a completely new structure, a substantial renovation, or the addition of an annex to ease some of the strain on the present building.

The annex and the renovation are the more complicated ideas, because they involve maintaining the present facility.

Semtner said an annex is a viable option but doesn’t address every concern.

“It would allow for immediate relief of several pinch points,” he said. “The infirmary is on the 13th floor today. If someone has a cardiac arrest, getting EMSA up there is a huge issue.”

Semtner said the existing jail’s kitchen also has problems with plumbing, so moving that would be beneficial. But he said perhaps the biggest benefit of an annex would involve the intake process. Adding an annex allow more flexibility to deal with different needs and situations, such as a person who is detoxing or someone who is violent.

“We talk about diversion programs,” he said. “When you’re brought into booking, you go through a door for evaluation. Maybe you end up in substance abuse treatment that’s through Door A. Or low-level offenders through another door. Right now, streamlining that process is not really achievable in the current facility.”

The renovation option seems to be the least popular. Even at a forum last month where some speakers railed at the cost of the new jail, none spoke in favor of renovating the existing building.

“If we renovate the current jail, it would have to be a substantial shift in its infrastructure to rehabilitate it to the point where better services could be provided,” Tardibono said. “My guess is the study will show that it’s not cost-effective to renovate.”

Whatever FSB’s report ultimately recommends, many community leaders want some sort of solution to be found, even if the intersection of criminal justice policy and tax dollars leaves some hesitant to support specific proposals at the local political level.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt simply wants to see a solution. Asked about the civic stalemate over the Oklahoma County Jail in April, days after a correctional officer was taken hostage and police fatally shot the perpetrator, Stitt called the situation “totally unacceptable.”

“It’s time for bold leadership. Let’s fix the problems. Let’s put the right team in place to tell us what the problems are, and then let’s go do either the bonding that we need to, or let’s change the structure,” Stitt said. “It’s obviously not working. We are all seeing that.”

Stitt said he wanted to see the three elected Oklahoma County commissioners, the OKC City Council and Mayor David Holt “to really get engaged in this process.”

“We almost just had a correctional officer killed,” Stitt said. “We need to solve this problem.”

‘What a medieval dungeon would be like’

Jess Eddy has spent plenty of time inside the Oklahoma County Jail, both as part of his work at an attorney’s office and also because his activism has landed him there on more than one occasion.

“It strikes you as what a medieval dungeon would be like,” Eddy said. “The stench there is a profound stench that permeates the place. There is peeling paint and discolored walls that are graffitied over that gives it a dystopian feel. I’ve never been in a cell there that doesn’t have urine or fecal matter.”

Given his experiences, one might assume Eddy would be clamoring for a new jail. But his feelings on the topic are mixed. He believes the jail needs to be demolished because he believes it’s inhumane to house people there, but he also has questions about where the funding for a new jail would come from.

Regardless of whether a new jail or annex is built, Eddy does not think it’s fair to spend all of the future CARES Act money to do it. He would like to see at least half of the funds directed to those suffering economically as a result of the coronavirus.

“I don’t think it’s equitable to those who are also vulnerable and to those who are still suffering,” Eddy said. “We still have endemic homelessness in our community. At least half of that money should go to low-bar social services toward people who are in need.”

But Eddy’s biggest concern is that a brand new jail would have too much space.

“The fear is that constructing a new facility will allow the [district attorney] and judges to over-incarcerate people, as they’ve done with the current jail,” he said.

Sara Bana is also involved in criminal justice reform and regularly speaks at jail trust meetings. In her eyes, the proof is in the pudding. She said Oklahoma County voters trusted their leaders to get it right back in the 1980s, and it didn’t happen. Given the current struggles with the jail, she sees little hope the latest incarnation of leaders will get it right either.

“The taxpayers were defrauded and bamboozled when the current county jail was built,” she said. “The construction problems that were found have never really been fixed.”

Bana sees the issues at the jail — things like bedbugs or broken telephones and doors — as signs of a larger problem that a new jail would only cover with window dressing.

“The bigger picture for me, as far as the future of the jail, is the population,” she said. “That could have been reduced to 600 to 800 people by now. There’s no reason to have 1,700 or 2,000 people in there, many of whom have mental health issues or are too poor to pay their bail. There’s no rational public-safety case to be made by keeping people like that locked up, whether it’s at this jail or a new one. It doesn’t make any sense.”

Rep. Jason Lowe (D-OKC) has long been a critic of the jail and does not believe the current building is salvageable, a point he made clear at a recent community forum on the subject.

Lowe, who is also a defense attorney and former public defender, has seen it all when it comes to the Oklahoma County Jail. He believes its conditions have an impact on outcomes for those inside.

“They talk to me about bed bugs, and they talk to me about unhealthy conditions,” he said during the forum. “They talk about the lack of heat that sometimes occurs at the jail, which I have experienced as well when I go visit them. There is a lack of staff that I’ve witnessed as well. I’ve seen all those things, and over the years it’s just gotten worse and worse. And, furthermore, I also see the District Attorney’s Office leveraging clients that are incarcerated as far as making sure they plead guilty because they want to get out of there. They’re going to take the first deal.”

A wish list for the future

No one knows what the future holds, but there are many hopes for what any change might achieve.

Jail trust member Francie Ekwerekwu also works at TEEM, an Oklahoma City organization that aims to break the cycle of incarceration. She sees the annex as the most likely step forward in the short term.

“I think what we’re seeing in reality, versus what I want to happen, is the annex,” she said. “The annex could be kind of a model that shows that a new facility can make the jail better if it includes services that help people exit the jail as quickly as possible, and with care and humanity.”

If a completely new jail makes the most sense, Ekwerekwu said there are several examples to draw on in the state.

“The Tulsa jail and the Cleveland County jail are the two that I would consider models,” she said. “They’re two stories. There’s plenty of space. There’s more sunlight and there are longer hallways with bigger pods. They’re both very clean, well organized and well staffed.”

But as things currently stand, the Oklahoma County Jail does not have the same funding streams as its better-performing counterparts. Oklahoma County is the only county in Oklahoma without a countywide sales tax, and OKC’s series of MAPS programs have absorbed much of residents’ appetite for a one-cent sales tax increase.

Would a quarter-cent sales tax for construction of a new jail and a quarter-cent sales tax for increased staffing and programming in the jail be palatable to the public? Local civic leaders rarely want to pitch the idea, and historic polling data have indicated such a campaign would be a heavy lift.

Despite his reluctance to support a tax to fund a jail, Eddy emphasizes that many in the current jail deal with mental illness and don’t get the care they need. In his eyes, whatever incarnation of the jail comes next, it would need to be set up to deal with those problems.

“I think we all agree that the facility is inhumane and not salvageable,” Eddy said. “A new facility is needed, but I see something that looks more like a mental health facility than a jail — a facility that is humane and functional. What we have now is neither.”

Arnall said she is unsure of the best option. But, above all, she wants detainees to be let out of their cells for more than an hour per day. She sees that level of confinement as one of the biggest problems currently.

“I’m trying to keep an open mind on all of it,” she said. “I’ve been assured in that building we can have direct supervision to get people out of the cells. Having a nicer facility would be great, but getting people out of their cells for their mental health and the safety of everyone there (is important). We also need programming. We can’t start programming unless they’re out of their cells, and we’ll never have enough employees to escort them everywhere. So if we build a new facility, I’d like it to be designed with all of that in mind.”

Tardibono said the current jail doesn’t necessarily fit the kind of offenders housed inside. For example, he cites changes in cultural mores that now see those who use marijuana illegally sent to diversion programs or cited by police rather than arrested, which has helped reduce jail populations, he said. The Oklahoma County Jail’s population has declined in recent years, from a high of about 2,600 about a decade ago to between 1,600 and 1,800 today.

“Our jail was built 30 years ago as a maximum security facility,” he said. “But the majority of the people there are either minimum or medium security. It doesn’t really fit the population. Whether a new jail is built or the current one is renovated, it needs to fit the population.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Will this time be different?

FSB is due to present its report to CJAC this fall, Tardibono said. At a recent listening event hosted by CJAC at 5th Street Baptist Church in northeast Oklahoma City, several dozen people spoke about their experiences with the jail.

There were references to bed bugs, a lack of blankets and bad plumbing. And there was also plenty of cynicism and distrust in the process. Artist and activist Jabee Williams said that attitude is the product of what he says is a pattern.

“The county has been this way for a long time,” Williams said at the public meeting. “People in power haven’t told the truth about it. The people who have been elected haven’t told the truth about the county, which makes it hard for us to trust and believe any kind of government when they talk about spending money.”

How any of the potential construction projects would be paid for is unclear. Some people are eyeing additional CARES Act money the county is due to receive sometime in the near future.

“People say it is or it isn’t available to use for that,” Arnall said. “If it turns out that we could use that money for the jail, which I’m hoping we’re allowed to do, it would be about $154 million.”

Tardibono is hopeful the public will be accepting of the idea of more money being spent to improve the jail. He said he and others have led hundreds of people on tours of the jail in recent years, ranging from Chamber of Commerce members to church groups. They usually walk out with a better understanding of its problems.

“I think a broad range of the public has started to dig into the negative headlines that we’ve all seen,” he said. “When you walk someone into a cell on a tour, and you shut the door behind them and let them feel what it’s like to be closed in like that for an extended period of time, they start to understand some of the issues that we talk about.”

Ekwerekwu said old feelings die hard for county residents who she said have borne the cost of what amounts to an expensive long-term mistake.

“The jail was built poorly, and given that it was a lot of taxpayer money spent on the project, people are still very bitter about that,” she said.