CLINTON — Just down the street from Washington Elementary School, a boy stood among a crowd of protestors, a mask pulled up over his nose and baseball cap pulled down above his eyes.

The boy was Dominique Lonebear, a student at the school, who had reported the week before that two other students had held him down in the school bathroom and cut off several inches of his hair, which had previously hung halfway down his back.

Speakers at the Sept. 10 protest included native men with long hair who talked about their own experiences being bullied or disparaged because of their appearance.

“We’ve all been through this,” one man said. “It’s time for them to start learning. They should have learned about our ways a long time ago.”

The men also spoke of the deep significance their long hair held — connecting them to their culture, their history and the earth.

Organizers of the march told the people assembled that they should shake Dominique’s hand if they got a chance, because he was a warrior for speaking out. They were there to support him and to say they believed his story, even though the school district and even the leadership of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, to which Dominique’s family belongs, had called his account into question.

The incident, along with the death of a Native American man in police custody that occurred the same week, had sparked something in the community.

In June 2020, when demonstrators gathered in Clinton to protest racism and police brutality, locals said such an assembly of frustrated citizens had not happened in recent memory. But now, little more than a year later, another crowd had gathered, and as they marched through the streets, their calls for greater respect and recognition reflected both old concerns and current tensions.

‘It’s 50 years later, and we’re still dealing with the same issues’

Among the protestors stood a man named Buddy Hatch, who carried a flag pole with an eagle’s head on top and had his long, layered hair held back with a bandana.

In 1972, when Hatch was in fifth grade, like Dominique, he was expelled from his public school in Canton, another western Oklahoma town about an hour north of Clinton. Hatch said he was kicked out of school because his long hair did not conform to the dress code.

“It’s 50 years later, and we’re still dealing with the same issues,” he said.

Hatch’s mother, Viola, was a prominent activist and the daughter of an Arapaho chief. She became defiant about her son’s expulsion.

“He has gone into the sweat lodge, and he knows a hell of a lot more than these kids who have gone to public schools,” she said.

Nonetheless, Viola and her husband, Donald, took the matter to court, arguing that requiring Buddy to cut his hair violated the family’s constitutional right to “raise their children according to their own religious, cultural and moral values” and that Buddy had been expelled in violation of his right to due process.

The American Indian Movement — an organization started in 1968 and which also organized this month’s Clinton march — called for a national boycott of schools that required native boys to cut their hair.

Although some things have not changed, Hatch said that, 50 years ago, if you carried an AIM flag through the streets, “You’d be shot.”

‘Don’t think it didn’t happen here’

The issue of cutting Indigenous children’s hair for school has a particular historical resonance: In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many Native children were forcibly taken from their tribes and families and sent to boarding schools, with the express purpose of “civilizing” them by disconnecting them from their cultures. Viola Hatch attended one such school herself — the Concho Boarding School near El Reno.

The long-term goal of boarding schools was to eliminate native cultures.

“All the Indian there is in the race should be dead,” said Richard Pratt, who founded one of the early boarding schools. “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Cutting children’s hair and dressing them in European-style clothes was one of the first steps toward assimilation.

The memories of boarding schools are particularly painful at the moment, after mass graves containing the remains of hundreds of children were found at similar schools in Canada. This discovery was mentioned by speakers at the march.

“Don’t think it didn’t happen here,” one said.

A federal investigation into the “troubled legacy of federal boarding school policies” was recently launched by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a president’s cabinet secretary.

The 1972 court case over Hatch’s hair ended when the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the expulsion had not violated the family’s religious rights.

“We cannot agree that the hair style regulation involves a sharp clash with a complete and religiously founded concept of raising children,” Judge William Holloway wrote in the decision.

The court did agree, however, that Hatch’s right to due process had been violated.

When speakers at the Clinton march referenced Viola Hatch and the legal fight over Buddy’s hair, they spoke of it as a victory.

‘It’s a man thing’

Standing in the crowd that had gathered at the Clinton police station at the end of the Sept. 10 march, Hatch recalled being in Dominique’s position almost 50 years ago.

“It was a lot of pressure. It was very stressful,” he said. “I got death threats from adults in other states.”

Even some in his tribe and family thought the issue was not worth all the trouble.

“I had uncles who would come pick me up and [without telling my mother] take me to the barber,” he said. “These were my uncles — chiefs. They just wanted it to go away.”

Similarly, the native community around Clinton is not monolithic in its reaction to Dominique’s account of what happened to his hair.

On Sept. 3, after reviewing video footage from the school on the day of the incident, Clinton Public Schools and Reggie Wassana, the governor of the the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, issued a joint statement.

“While some details remain disputed, Clinton Public Schools and Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal leadership agree that the initial report that the student was held down by two older students while his hair was cut is inaccurate and did not occur,” the statement read, while promising a continued investigation.

Many protestors at the Sept. 10 march were dismissive of the statement and said they believed Dominique absolutely.

“All Reggie does is smooth the waters,” said one protestor. “He doesn’t want to address it. And where is he? Shouldn’t he be here?”

Cetan Sa Winyan, the director of the American Indian Movement’s Indian Territory chapter, described the statement in an interview as “blowing smoke.”

At the march, she criticized Wassana’s participation in the statement as “colonialism at its finest.”

“You stand with your people, regardless,” she said.

Wassana told NonDoc in an interview that he believes there has been a “disconnect” between the intention of the statement and the reaction some have had to it.

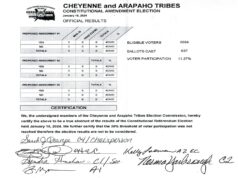

“I think there was an adult agenda, and it seems like the boy was lost in the agenda” Wassana said, adding that it is campaign season for the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes and that topics become political around elections.

Wassana said officials reviewed video footage from 20 minutes before Dominique entered the bathroom and 20 minutes after, and nobody else is seen going in. He said Dominique’s family has not identified any suspects, saying he was jumped from behind and couldn’t see their faces.

In the absence of suspects, Wassana said he believed it was best to take a “holistic” approach to making sure Dominique had the support he needs and pushing the school district to address bullying and emphasize cultural sensitivity and diversity.

“I think we need to let the younger [native] kids know it’s perfectly fine, it’s OK [to have long hair],” he said. “But we’re not going to reach those people until other students or teachers or educators understand that we grow long hair because of our culture and heritage. It’s not because we want to look different. It’s because we are different.”

Wassana said the school district has indicated it would take action and welcome change, but he was cautious about expressing too much optimism.

“We need to see implementation,” he said. “Until we see implementation of change, we’re not going to be satisfied.”

Wassana mentioned that he also had long braids as a boy and experienced bullying because of it. Once, in second grade, a teacher even pulled his hair, he said.

“At the time, we had no recourse,” Wassana said. “We couldn’t go to anybody. I couldn’t tell my mom. Back then, unfortunately, you had to fight your way through school as a minority.

“I don’t know if everybody understands what we go through as young boys with braids. It’s tough.”

Hatch, for his part, was circumspect about Dominique’s story.

He mentioned that some people were saying Dominique cut his own hair and recalled times when, as a boy, he thought about doing the same.

During his legal battle, Hatch said there were times that, like his uncles, he wanted to just cut his hair and run away from the situation. But he stayed the course because, “I had heroes with long hair.”

Even if Dominique had cut his own hair, it did not invalidate the point of the march in Hatch’s eyes, because it would still be the case that a young child had been pressured by the dominant, white culture to abandon his own traditions.

Hatch used to be made fun of and called a girl. Even today, he said, he sometimes gets mistaken for a woman. But he believes it’s important for men from his culture to keep traditional ways alive by wearing their hair long.

“Some guys think it’s a little boy thing,” he said. “But it’s not. It’s a man thing. It’s an ancestral thing.”

‘Whose land? Our Land!’

History was present throughout the Clinton demonstration: in calls to educate white society about Native ways, in demands to change the name of Custer County, and particularly in assertions of tribal sovereignty.

The 2020 march was focused on local events — particularly the deaths of two native men who had been shot by police — but it was inspired by the national wave of protests that followed the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

If this year’s protest was inflected by a broader event, it was perhaps the U.S. Supreme Court’s McGirt decision, which affirmed the continued existence of the Muscogee Nation reservation, and which has been the basis for the recognition of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole reservations as well.

When the demonstrators paraded through Clinton, from the elementary school to the police station, they chanted, “Whose land? Our Land!” One of the biggest cheers of the day came when a speaker said, “Let’s let the white supremacists know this is Cheyenne Arapaho land!”

Speeches about the need for better education about native culture in schools — to prevent bullying — intertwined with statements heralding a coming recognition of native people’s right to the land.

Before the marchers set off through the streets, a group of men gathered around a drum, beating a pulsating rhythm and singing.

A woman who had come in from Elk City for the protest, who said she had experienced prejudice all her life, looked on from the shade on the side of the street.

“I don’t know what the song is,” she said. “Maybe it’s a war song. Maybe they’re saying, ‘Watch out, white people. Here we come.’”