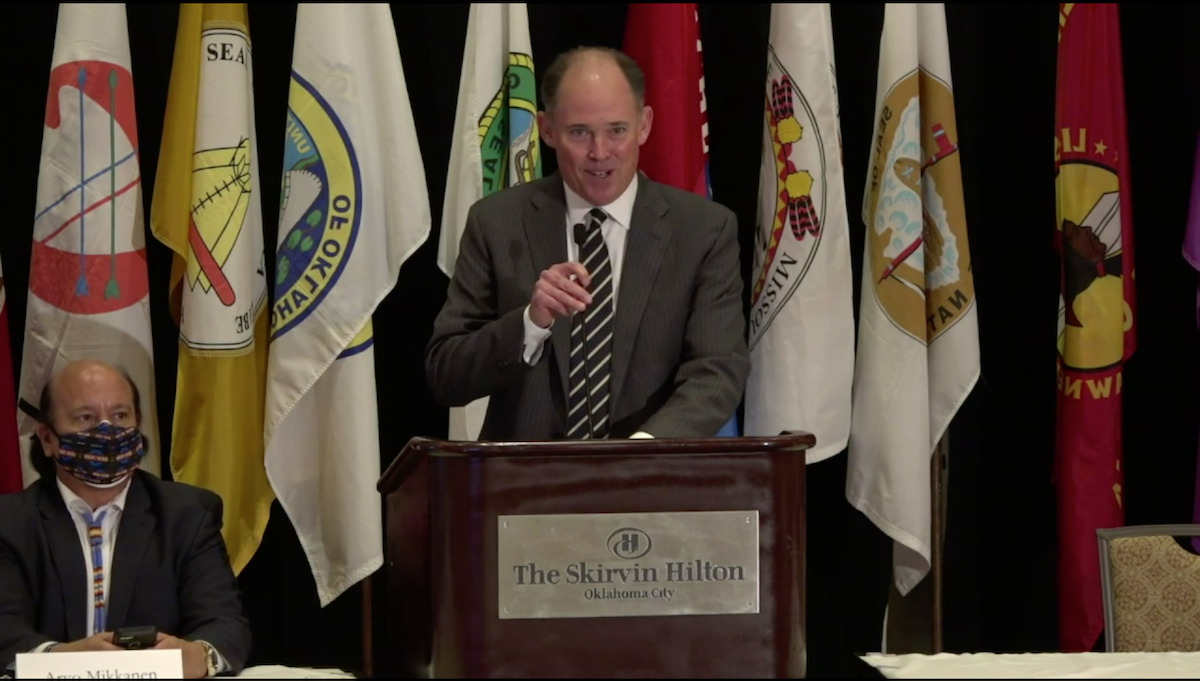

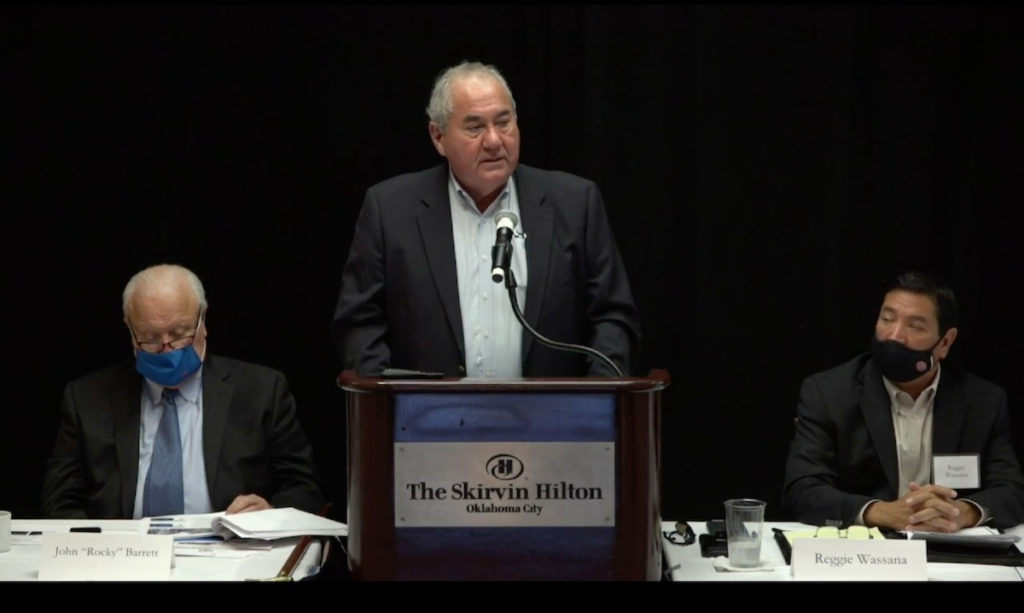

The feud between state and tribal officials over the 2020 landmark Supreme Court ruling in McGirt v Oklahoma continued throughout this week’s 2021 Sovereignty Symposium, an annual event that features an array of panels and public discussions on Indigenous affairs and state relations. The event took place Monday and Tuesday at the Skirvin Hotel in Oklahoma City, but it was able to be viewed online via registration.

During Monday’s first panel on criminal law, executive leaders of the Cherokee, Muscogee, Chickasaw and Choctaw nations each discussed their respective tribe’s expanding criminal justice systems. Seminole Nation Chief-elect Lewis Johnson was absent because he had to attend a funeral, a co-moderator noted.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. set the tone during his opening remarks with a direct message toward Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt and Attorney General John O’Connor.

“Can anyone believe in 2021, in the United States, that someone is with a straight face asking the Supreme Court of the United States to break a promise to an Indian tribe?” Hoskin said.

‘Enemies of sovereignty’

The 5-4 McGirt v Oklahoma ruling affirmed the Muscogee Nation as an Indian Country reservation as defined under 18 U.S.C. 1151a. Justices said the reservation had never been disestablished by Congress. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals followed with decisions stating that the SCOTUS ruling also applies to the Cherokee Nation, Choctaw Nation, Chickasaw Nation and Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. This means only a tribe and the federal government — not the state — have criminal jurisdiction over major crimes that occur on reservation land involving tribal citizens.

Since the rulings, Stitt has proclaimed that his administration wants to have the Supreme Court ruling overturned or its impact narrowed, filing several legal challenges in that effort. Hoskin said Monday that state officials are trying to push a false narrative pertaining to increased criminal activity on Indian land, referring to Stitt and O’Connor as “enemies of sovereignty.”

“They’re trying to convince the country, not just people in Oklahoma, but the country, that the sky is falling,” Hoskin said. “That the tribes cannot possibly be trusted with the responsibility to create a criminal justice system. I think the opposite is true.”

Muscogee Nation Chief David Hill referred to the state’s narrative as a “chaos campaign.”

“The goal of this ‘chaos campaign’ seems intended to lead to one of two outcomes: Passing legislation to overturn McGirt or having the Supreme Court overturn its own decision,” Hill said.

Choctaw Nation Chief Gary Batton echoed Hoskin and Hill’s remarks.

“There has not been one person who has committed a crime that has fallen through the cracks,” Batton said.

Hoskin highlighted the growth of the Cherokee Nation’s criminal justice system. He said his tribe has committed $30 million to public safety this year, hiring 13 more marshals, hiring more prosecutors, hiring more district judges and doubling the number of victim service advocates within the nation, as well announcing plans to open a courthouse in Jay.

Hoskin later said the five tribes “have had almost 7,000 felony or misdemeanor cases” since the SCOTUS ruling, with about 2,000 of those cases in the Cherokee Nation. Prior to the ruling, only a few dozen of those cases would have been held within tribal courts.

Ryan Leonard — Stitt’s special counsel on tribal affairs — spoke during the afternoon panel and addressed Hoskin’s claims from earlier that morning of state officials being “anti-sovereignty.”

“I know there’s been talk of ‘enemies of sovereignty’ and ‘anti-sovereignty,'” Leonard said. “I would also claim that those are false narratives.”

The state’s ‘three C’s’

Leonard said that following the SCOTUS ruling, the state discussed its path forward by placing their options into three buckets, which Leonard called “the three C’s”: compacting, Congress and the courts.

Regarding compacting, Leonard recalled that the five tribes disagreed on the value of striking a series of compact agreements on public safety jurisdictional issues.

“We had two tribes that wanted the option to be able to compact on criminal jurisdiction, and that requires federal legislation,” Leonard said. “We had three tribes (…) that were actively opposed to legislation or compacting.”

Leonard referenced a drafted bill by U.S. Rep Tom Cole — a Chickasaw Nation citizen — which would apply to the Cherokee and Chickasaw nations, but not the Muscogee, Choctaw and Seminole nations.

The legislation was called “unnecessary” by Batton, the Choctaw chief, and some pointed to “ulterior motives” in the bill regarding relationships with smaller tribes.

Leonard then spoke on the scope of the McGirt v. Oklahoma ruling, saying agencies of the federal government have applied the ruling beyond criminal jurisdiction into civil jurisdiction issues.

“The McGirt decision very explicitly says that this decision is limited in scope to the federal Major Crimes (Act). It didn’t say anything about civil jurisdiction,” Leonard said. “However, there are those amongst the tribal communities and our partners and friends in tribal leadership — as well as now the federal government itself — who’ve used McGirt much more broadly.”

Regarding civil jurisdiction, Leonard specifically mentioned the Department of the Interior stripping Oklahoma of surface mining jurisdiction on the five reservations, which occurred in May.

After falling short on an agreement regarding federal legislation with tribes, Leonard said, “That left us really no other option than the courts, which is where we are today.”

During Monday’s first panel, Chickasaw Nation Gov. Bill Anoatubby acknowledged that the current rift between tribes and the state is making collaboration difficult.

“Just as Oklahoma guards its sovereignty from federal overreach, we too will zealously defend our sovereignty from Oklahoma’s intrusion or disregard,” Anoatubby said. “When sovereigns abandon their respect for the right of other sovereigns, our ability to work together breaks down and really can become difficult.”

Tribal Access Program

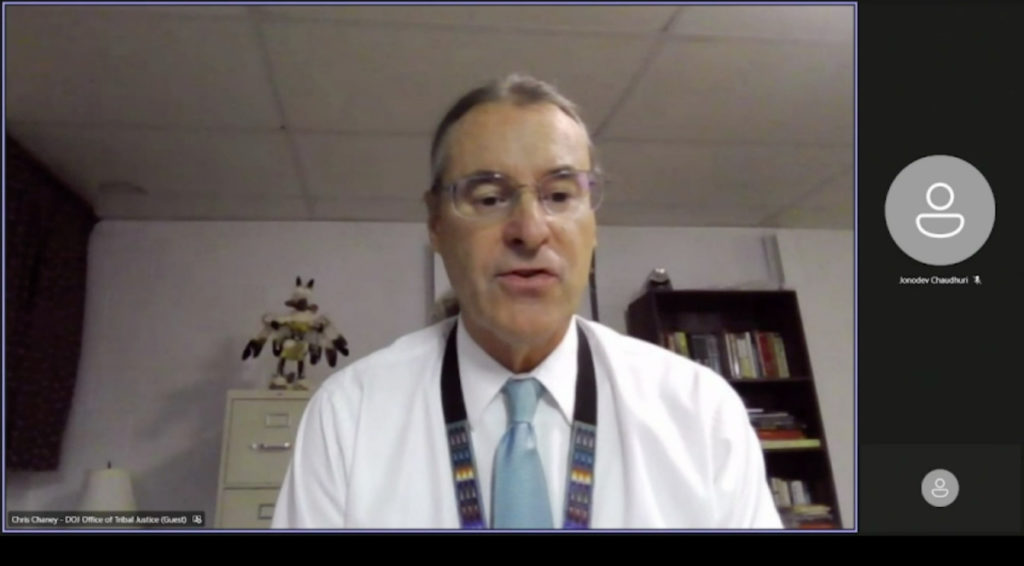

During the Monday afternoon panel, Christopher Chaney — senior counsel for law enforcement and information sharing at the U.S. Department of Justice — discussed the federal Tribal Access Program, which offers national crime data to federally-recognized tribes in an effort to uphold public safety in tribal communities.

The program was launched in 2015 by the DOJ, and Chaney said 12 Oklahoma tribes now participate in the program, including the Muscogee, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole nations.

The program allows for police departments and other law enforcement agencies to search for information on stolen property, missing or wanted persons, criminal histories and more. The program offers access to non-criminal data as well.

“Criminal justice information is important across reservation boundaries, on other reservations, or even off reservations,” he said. “It helps police departments, tribal police departments and non-tribal police departments to be able to do their jobs.”

‘Interwoven economic futures’

During Tuesday’s panel on tribes’ economic futures, leaders discussed their nations’ economies and where various ventures might take their tribes.

Early conversations between panelists also examined the topic of blood quantum, which refers to a person’s genetic percentage of “Indian blood.” Blood quantum rules within tribes can be controversial, with some Indigenous people criticizing them as a colonialist concept and others supporting thresholds as a way to preserve community.

Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Gov. Reggie Wassana spoke on the tribes’ recent election to decrease their blood quantum requirement from one-fourth to one-eighth. Wassana said he expects an additional 3,000 to 6,000 citizens could enroll in the tribes as soon as “six to eight months.”

Wassana also mentioned the idea of purchasing lands in Colorado, where the Cheyenne Tribe originated.

“We’re originally from Colorado, so that’s something we’re looking at — purchasing land in Colorado,” he said.

Deborah Dotson — president of the Delaware Nation, which is located in Anadarko, about 60 miles southwest of Oklahoma City — said her tribe eliminated its one-eighth blood quantum requirement and switched to lineal descent by passing a constitutional amendment in March 2019.

At the time of the election, Delaware Nation had 1,452 enrolled citizens. Today, they have 2,043 enrolled citizens, Dotson said.

Oklahoma State Rep. Meloyde Blancett (D-Tulsa) spoke on the importance of state and tribal officials working together, stating that “economic futures are interwoven”.

Blancett also noted that if tribes were an industry, they would rank 11th largest in the state by employment, a line that drew applause from tribal panelists.

Osage Nation Principal Chief Geoffrey Standing Bear said his tribe is using American Rescue Plan Act funding to develop a residential drug and alcohol treatment center.

“That’s where we’re putting this ARPA money, because we can prove to you through our studies that this kind of stress through the pandemic, this kind of world that we’re living in, does affect our well-being, our mental health, our diets,” Standing Bear said. “Those things cause different kinds of sicknesses.”

Standing Bear referenced differences in life expectancy when people live in a more rural area as opposed to a city.

“If you’re 60 miles away in Tulsa, and you’re in a similar situation in Osage (County), as where I live in Pawhuska, your life expectancy is 10 years less,” Standing Bear said. “Our non-federal monies, our tribal funds, we use half of it for health. That’s what we’ve got to do. We’ve got to be healthy. We’ve got to be educated.”

During closing remarks Tuesday, Citizen Potawatomi Nation Chairman Rocky Barrett voiced his gratitude for the partnership that he and the Citizen Potawatomi Nation have created with members of the Oklahoma Legislature, but that he hoped a similar partnership could develop with the executive branch at some point.

“This partnership we’re forging with Oklahoma, I’ve noticed in my area in particular, the growing partnership and feeling of working together with the representatives of the Legislature. Hopefully that will also happen with the executive branch, at some point,” Barrett said. “There’s a great future ahead for Oklahoma by working together with the tribes, because we bring in sources of revenue that are not available to state and county and municipal governments within the state.”

Barrett and leaders of the City of Shawnee recently announced “Shawnee Aligned,” a cooperative agreement between the municipality and the tribal nation aimed at recruiting businesses to the area. The agreement formally ended a legal dispute over land south of the North Canadian River that the city had annexed in 1961 and that the Citizen Potawatomi Nation said was taken from their tribe illegally.

Barrett said Oklahoma’s rural communities are all tied to tribal communities and need to work together.

“We are where we are by an act of Congress. We can’t go anywhere else, so 90 percent of those jobs (for tribal citizens) are rural jobs,” Barrett said. “Creating jobs in Oklahoma City and Tulsa is a whole lot easier than creating a job in Wanette, Oklahoma, or even Watonga. And so those jobs out in rural Oklahoma are just that much more valuable and have that much more impact on the economy of the state.”