Something special happened this year on Feb. 1: the Lunar New Year and Black History Month began on the same day.

To mark the occasion, many people shared their favorite Black-Asian duos from film, TV and real life.

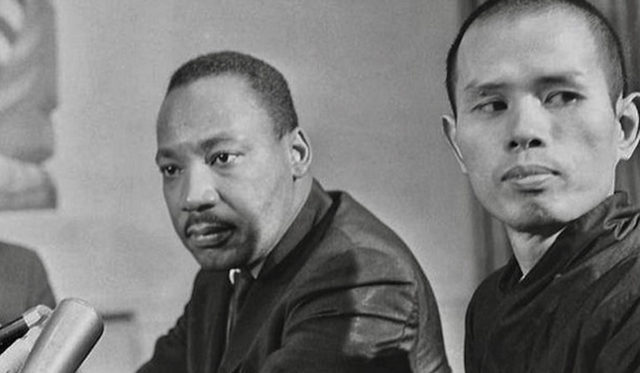

This reminded me of one of my own favorite historical duos: the civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Thích Nhất Hạnh, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk and peace advocate who died in January.

The two shared a special friendship, built around the principles of peace, justice and liberation. This relationship had a major impact on King, leading him to speak out against the Vietnam War when many of his closest allies and advisers urged against it.

In 1967, King even nominated Thích Nhất Hạnh for the Nobel Peace Prize, writing, “I do not personally know of anyone more worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize than this gentle Buddhist monk from Vietnam (…). His ideas for peace, if applied, would build a monument to ecumenism, to world brotherhood, to humanity.”

King’s friendship with Thích Nhất Hạnh is not unique, however. It is part of a long tradition of Black-Asian solidarity.

The important history of solidarity

In the late 19th century, as American political discourse was marked by anti-Asian sentiment — shown most notably in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act — the abolitionist Frederick Douglass spoke on behalf of Chinese and Japanese immigrants in his “Composite Nation” speech. In the 20th century, as decolonization was spreading, leaders of African and Asian nations convened at the Bandung Conference to promote cooperation and imagine a future together.

The shared goal of tackling racism and white supremacy has fueled Black-Asian collaboration in the past few years as well, including at the local level. In Oklahoma City, the Asian District Cultural Association supported Black neighbors after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Similarly, Black activists, policymakers, and media moved quickly to support the local Asian community after a shooter in Atlanta killed eight people, six of whom were women of Asian descent.

I am keenly aware that my history, as an Asian American in this country, is tied to the activism of Black Americans. Illustrating this connection is Bayard Rustin, a Black, gay activist during the civil rights movement who helped organize the March on Washington 1963, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, Rustin visited refugee camps in Thailand, where he saw Vietnamese refugees living in horrific conditions and spoke to them about their desire to escape oppression and war.

At the time, most Americans opposed the idea of changing immigration laws to allow Southeast Asian refugees to resettle in the United States. But Rustin sought to change public opinion, urging America to open its borders. Taking out an advertisement in The New York Times, Rustin and other Black leaders publicly supported the refugees.

It was partly because of this advocacy work that Southeast Asian refugees were finally allowed to start a new life here in the United States. Indeed, those same refugees helped form the nationally renowned Asian District in Oklahoma City. Also among those refugees were my parents and grandparents.

We need to stand together

The many opportunities I have been fortunate enough to enjoy would not have happened if my family had been rejected from settling in this country. For that, I and other descendants of Southeast Asian refugees must remember the Black civil rights activists who paved the way to allow us to live here.

Of course, Asian and Black communities have not always had perfectly harmonious relationships. Interracial conflict unfortunately exists, and tensions between Asian and Black communities severely escalated in the 1990s. Although Black and Asian Americans share goals in tackling racism, the differing experiences of being Black and Asian people in this country can often be the source of conflict. For example, recent debates around affirmative action are putting a wedge between Asian Americans and other minority groups.

However, I remain optimistic. Conversations are happening. History can be our inspiration.

Solidarity, after all, is more than just a slogan. It is the feeling and practice of interdependence. It recognizes the connections between different forms of inequity and injustice. It highlights the need to stand together.

In the face of racism, xenophobia and division, solidarity tells us that we share a fascinating history — and a future.