After already indicting one legislator in December, an Oklahoma County grand jury concluded its term today and filed a report about its inquiry into tag agency legislation and the actions of Pardon and Parole Board members, whom grand jurors said were subject to “improper political pressure” from Gov. Kevin Stitt. Over multi-day sessions held each of the past seven months, the grand jury issued 65 subpoenas for testimony and records and heard from a litany of influential state leaders.

“This grand jury states that the governor of Oklahoma should studiously refrain from directing his [Pardon and Parole Board] appointees as to the manner in which they should vote as board members once they are appointed or thereafter, or attempting to direct these appointees on how to make board personnel decisions once the board members are appointed or thereafter,” the grand jury report states.

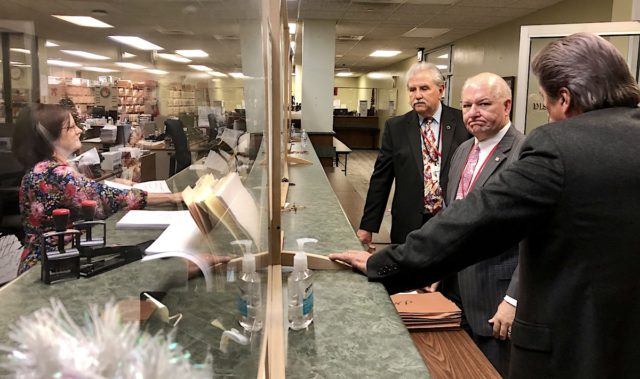

Regarding their investigation into a pair of 2018 and 2019 tag agent bills that led to the conspiracy indictment of Rep. Terry O’Donnell and his wife, grand jurors said they will let District Attorney David Prater decide “whether these cooperating witnesses should also be charged with some of the offenses charged in the December 2021 indictment.” No new charges were filed today.

Based on details contained in today’s report, the indictment of the O’Donnells and other information directly observed by NonDoc, cooperating witnesses include — but are not limited to — House Speaker Charles McCall (R-Atoka), House Civil Judiciary Chairman Chris Kannady (R-OKC) and Senate Appropriations Chairman Roger Thompson (R-Okemah).

“The grand jury worked very hard in an attempt to answer serious questions about the two investigations noted in the report,” Prater said in a statement to NonDoc. “I greatly appreciate their sacrifices and their service to the citizens of Oklahoma.”

The 65-page Oklahoma County grand jury report is embedded below. Names of those investigated or interviewed are not listed in the report, but other identifying information is included.

‘These contracts are extremely lucrative to most motor license agents’

Prater requested to seat his grand jury in September, telling the Oklahoma County presiding judge that he sought to examine issues related to the county’s “jail trust” and the state Pardon and Parole Board.

From Dec. 17, 2021

Rep. Terry O’Donnell, wife indicted by grand jury over tag agency by Tres Savage

But when the grand jury’s first indictment came in December, it showed that Prater had used the investigative body to continue working a case that he had begun in front of the state’s multi-county grand jury earlier in 2021. Rep. Terry O’Donnell (R-Catoosa) and his wife, Teresa, were indicted Dec. 17 on a combined seven criminal counts related to his authorship of a bill that legalized her ability to become a state-appointed tag agent in Catoosa.

Prater had begun the investigation into O’Donnell in front of the state’s multi-county grand jury, which is run out of the Attorney General’s Office. But Prater told NonDoc he was denied the opportunity to continue his examination of the O’Donnells before the multi-county grand jury after then-Attorney General Mike Hunter resigned in May 2021. Prater said Hunter had repeatedly asked him to investigate Terry O’Donnell for the tag agent bills and that Hunter had said he had a “conflict,” meaning he could not lead the investigation himself.

Earlier this spring, Prater said he had investigated an allegation about how Hunter convinced McCall to stall an O’Donnell bill regarding state agency contracts with private law firms, a policy that Hunter opposed.

Thursday’s grand jury report about the tag agency matter, however, focused primarily on making a series of recommendations for reforms regarding the Legislature and the Oklahoma Tax Commission, which now appoints tag agents.

Those Oklahoma County grand jury report recommendations include:

- restoring the prohibition against legislators and their direct family members being designated state tag agents;

- changing the legislative terminology for not voting on a matter in which a lawmaker has a direct interest from “constitutional privilege” to “constitutional duty”;

- creating rules in the House and Senate “requiring the preparation of a ‘Legislation Conflict of Interest Impact Statement’ regarding proposed legislation similar to those applicable to the requirements for a fiscal impact statement for legislation.” The report suggests having either the Attorney General’s Office or the Oklahoma Ethics Commission produce such reports;

- broadening their “active investigation” of applicants for motor license agents conducted by the Motor Vehicle Division of the Oklahoma Tax Commission “to include an independent investigation of all factors set forth and include a determination of whether any member of the Oklahoma Legislature would be directly or indirectly interested in any Motor License Agent contract awarded.”

The grand jury report also outlines a broader picture that criticizes how state-appointed tag agents — officially called motor license agents — are selected.

“These contracts are extremely lucrative to most motor license agents,” jurors wrote. “For example, in the case this grand jury investigated regarding the Catoosa Tag Agency, we found that though it was one of four motor license agencies located in Rogers County, the application for motor license agent filed in 2019 anticipated annual expenses of the motor license agent of $177,200 against the average gross collections of that motor license agency of $287,175.67, and thus anticipated it would realize a net profit to the motor license agent of $109,975.67. The actual gross revenues to that motor license agency during calendar year 2021 had grown to $332,343.41. This represents an astounding return upon an initial investment by the applicant of $100 paid by the applicant to the Oklahoma Tax Commission.”

The report states that Oklahoma had 274 active tag agents in 2021 that retained $59.5 million in fees from their customers. Collectively, those tag agents collected $941.8 million in taxes and fees that were deposited with the state.

“The Oklahoma Tax Commission apparently does not track motor license agency expenses by agency, so net [Motor License Agent] fees is difficult to discern to determine efficiency of such operations,” the report states.

RELATED

The ‘weird political misadventure’ of two tag agent bills by Tres Savage

The report also states that the manner in which tag agents are selected by the Tax Commission — in particular with “contingency retirements” that were legalized by a 2018 bill authored by Kannady — prevents “open and fair competition for such potentially lucrative contracts.”

“Because they are currently considered ‘independent contractors’ and not regularly appointed state officers and employees, the appointment of applicants to become motor license agents is not included within statutes prohibiting invidious employment discrimination in state employment,” the report states. “This grand jury has repeatedly heard witness after witness from the Oklahoma Tax Commission unable to state how applicants are openly and fairly recruited when existing motor license agents need to be replaced. Not only are such vacancies not regularly advertised, but a 2018 amendment to Section 1140 of Title 47 which governs the appointment of motor license agents statutorily restricts the discretion of the Oklahoma Tax Commission in appointing replacements for retiring motor license agents.”

The report states that, of 14 tag agents replaced in 2019, 10 of the new tag agents were selected owing to the letters of “contingent resignation” authorized by HB 3278 in 2018. (Contingent resignation letters are submitted by existing tag agents who state they plan to retire if the Tax Commission appoints their desired replacement.)

“The principal House author of that bill has given sworn testimony that this provision was intended by him to ‘streamline’ the process of motor license agent transfers so that there would not be a ‘gap’ in operation causing the motor license agency to shut down while a replacement was approved, thereby inconveniencing the portion of the public normally served by that motor license agency,” the report states. “That eliminated the possibility of allowing open and fair competition for such potentially lucrative contracts and any fair opportunity for recruitment of replacement motor license agents, even among persons currently employed by the retiring motor license agent. We also note that ‘contingent resignations’ also violate the spirit if not the letter of existing state policies designed to encourage and effect participation of minority and diverse businesses in state contracts.”

The grand jury recommended repealing the contingency retirement language from state statute.

“We also recommend that the equal opportunity provisions already part of Oklahoma law encouraging fair and diverse participation by potential contractors in the awarding of state contracts should also be required to be followed in the selection of motor license agents and the awarding of motor license agent state contracts,” the report states.

While no new charges were filed Thursday, grand jurors emphasized that charging decisions could still be made beyond the conclusion of their term:

Oklahoma permits the initiation of criminal charges by either grand juries such as this one or by a district attorney having jurisdiction over the venue for the crime. Criminal offenses may be prosecuted either upon an indictment brought by a grand jury or upon an information brought by a district attorney since indictments and informations are considered ‘concurrent remedies’ under Oklahoma law.

While at the time the grand jury brought the indictment it returned in December 2021, it had received and fully considered all of the facts it required regarding the matter of whether charges set forth in that indictment should be brought against the named defendants in that case, this grand jury did not then have sufficient time either then or since to fully consider whether other persons who also may be culpable under the facts alleged in that case should also be charged. In that regard, we were and are aware that some of the persons who may also be culpable of the offenses alleged therein freely and voluntarily testified before this grand jury or the Oklahoma multi-county grand jury and have otherwise cooperated and assisted these grand juries in their several investigations of these crimes. Due to time that we have devoted to investigations of other matters that we have conducted, we have not deliberated further upon whether or not other persons should be charged in that matter.

Pardon and Parole Board decisions examined

Prater and his grand jury’s investigation into the Pardon and Parole Board began in October, but he was the second prosecutor to be involved in the matter.

In March 2021, Stitt called for the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation to look into whether incarcerated individuals had been improperly re-docketed before the board. Then-Attorney General Mike Hunter selected former U.S. Attorney Brian Kuester to oversee the investigation as a contracted special prosecutor.

Prater said the hard copy he received of the OSBI report on the Pardon and Parole board matter was dated Oct. 3. But in a November interview with NonDoc, new Attorney General John O’Connor said Kuester’s oversight of the Pardon and Parole Board investigation was ongoing.

“The OSBI has not finished its investigation and given it to Mr. Kuester yet, so I haven’t seen any of that,” O’Connor said Nov. 3.

Five weeks later, on Dec. 9, Kuester submitted his resignation letter to O’Connor, calling the Pardon and Parole Board investigation “thorough and complete.” Kuester’s letter said “members of the (multi-county) grand jury should be commended for their commitment to following the law and finding the truth,” but it is unclear to what extent Kuester utilized the multi-county grand jury, which had concluded its term in September.

Prater ultimately presented information about the Pardon and Parole board investigation to his grand jury, and the report released Thursday highlighted concerns about whether the spirit of the Open Meeting Act was violated in meetings with Stitt.

This grand jury heard testimony that what would eventually become an official quorum of board members reportedly met with the governor of Oklahoma before their appointment and taking office, at which time decisions were made about upcoming votes of these board members once these board members took their seats on the board, not only in regard to how they would handle their duties regarding deciding paroles, commutation recommendations, and pardon recommendations, but also regarding the dismissal of then-director of the agency. At the time of this conversation, the individuals had not taken their seats yet, nor had any yet taken the required oath of office. However, such a meeting clearly violates the spirit of the Open Meetings Act, and clearly renders the future board less than the independent authority contemplated by the Oklahoma Constitution.

The grand jury report also notes that state law requires the Pardon and Parole Board to publish and distribute to the Legislature annual reports regarding its activities, but jurors found that no such report has been provided since 2018. One Pardon and Parole Board member allegedly objected to the form of the reports.

“Because of that one board member’s objection, these reports were never submitted to the whole board for a vote to approve and to make the reports available to the Legislature and public,” the report states.

The grand jury recommends that the reports be immediately reviewed and filed by the board so that the Legislature and public can determine how board members voted and be informed about the “unusual” increase in commutation numbers.

The report also recommends that the Pardon and Parole Board publish recidivism rates, which the National Institute of Justice defines as a relapse into criminal behavior, for individuals granted commutation. The report states that the Legislature should define the term “recidivate” for the board, as there is no official legal definition of what the term means.

‘A tragedy may have been prevented’

The Oklahoma County grand jury report details the events surrounding the January 2021 release of Lawrence Anderson from prison. Less than a month later, Anderson was arrested for a grisly triple-murder. According to the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation, Anderson confessed to killing and cutting the heart out of Andrea Lynn Blankenship, a Chickasha woman who lived near his aunt and uncle.

OSBI has said Anderson then cooked Blankenship’s heart at his aunt and uncle’s house, killing his uncle Leon Pyle, wounding Pyle’s wife and killing Kaeos Yates, their 4-year-old granddaughter.

Concern about Anderson’s release centered on the fact that he originally applied for commutation but was denied in July 2019. He was re-docketed in October 2019, and his Stage 2 hearing was held in January 2020, with the board voting 3-1 to recommend a commutation to Gov. Kevin Stitt. Stitt approved the recommendation in June 2020, commuting Anderson’s sentence to nine years. Anderson, who had received a 20-year prison sentence in 2017 for drug crimes, was released Jan. 16, 2021, after serving three years in prison.

From the grand jury report on Page 43:

There is one additional question related to Lawrence Anderson that is puzzling to the grand jury. Lawrence Anderson was denied a commutation recommendation when he went through the commutation process in January 2019. A short seven months later, he submitted a much shorter application, [was] placed onto a commutation docket in January 2020, and [was] granted a recommendation for commutation. The grand jury is unable to find anything in the public records or from testimony that describes some change in Anderson’s circumstances over those seven months that would account for the change from an unfavorable to a favorable recommendation. This total turn-around in voting showcases the clear lack of objective criteria used by the board, and any requirement that they use any criteria at all if they choose not to.

As citizens, this grand jury finds that this case alone demonstrates the need for discernible objective criteria to be used by the board in making commutation recommendations. The records reviewed and testimony received is void of any evidence that can account for the change from an unfavorable commutation recommendation to a favorable commutation recommendation.

The testimony further reveals that at least one high level member of the administrative staff became aware of the Anderson case being docketed in error. The discovery was made made at a time when it could have been easily corrected. However, a unilateral decision was made by one person not to bring the error to the attention of the board or the governor’s office. This failure to immediately bring the error to the board’s attention prevented the board from correcting the error before the case went to the governor for approval. Failure to notify the governor immediately of this error also prevented the governor’s office from denying the recommendation to commute Anderson’s sentence. A tragedy may have been prevented.

The report states that the grand jury was unable to determine with “absolute certainty” who placed Anderson back onto the docket. Further, the grand jury found that, beginning in 2019 until mid-2021, the commutation process was used as an “early release mechanism” that was anything but “rare.”

“The grand jury recommends that the board follow its own definition of commutations as being rare,” the report states. “The jury recommends that commutations not be used as an early release mechanism nor as a method of changing sentences. As citizens, we are required to follow the law and rules, and the board should be required to follow theirs as well.”

The grand jury also issued a series of findings and recommendations for future practices of the Pardon and Parole Board:

- The grand jury questions the authority of the Legislature to retroactively change the range of punishment for any crime;

- The Pardon and Parole Board lacks sufficient funding to carry out the duties of investigating cases properly and completely;

- Better vetting should be undertaken to determine if conflicts of interest appear to exist between board duties and outside employment and political goals of board members;

- The power to appoint board members should not allow for one authority to appoint a majority of board members;

- The District Attorney’s Council should have a full-time representative at the Pardon and Parole Board offices;

- The governor’s office should have a dedicated staff member to double check those persons being recommended for release of any kind;

- The board should explore and purchase updated software to allow for easier and more complete information to be available for board members;

- The Pardon and Parole Board is not qualified to make determinations related to “new evidence,” meaning such items should not be considered by the board;

- Inmates should be required to attach copies of judgments and sentences for all their convictions to their application;

- The Legislature should adopt a mechanism that allows an interested party to challenge the impartiality of a particular board member, and alternate members should be appointed so that a missing member’s vote is not considered a “No” vote;

- Dockets should be listed by the county from which the conviction occurred, and the dockets should be limited to manageable quantities;

- The board should be required to post audio or video recordings of each board meeting, and these records should remain on the board’s website for a period of five years;

- The board should require the executive director to designate one or more specific persons to oversee and fact check each application on any docket heard by the board;

- Government workers should be required to use government email systems when discussing government business;

- The Legislature should enact some penalty that attaches for willful failure by a public body to follow its own published rules and policies.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

Read the full Oklahoma County grand jury report

(Editor’s note: Megan Prather and Matt Patterson contributed to this report.)