DURANT — Deep in southeast Oklahoma, there’s a running joke that, as far as the Legislature is concerned, Oklahoma ends in McAlester, a city about an hour and a half north of the Texas border.

Durant, the county seat of Bryan County, sits about 10 miles north of the Texas border. Such areas have an information ecosystem all their own. Far from the center of either Oklahoma or Texas, places like Durant can end up as information outcasts, grafted into the coverage area of the closest major city, even if it’s in a different state, or left in a dead zone when it comes to news that affects the local community.

“Often or almost always in rural Oklahoma, we are forgotten,” said Janet Reed, executive director of the Durant Area Chamber of Commerce. “We are the grassroots of what has contributed to our great state, and we are very proud of what our contributions have been. But we also have voices, and we want them heard.”

The no-man’s-land treatment of border counties can affect many aspects of life and can even be deadly, as when EF3 tornadoes hit Bryan County in 2015 and 2019, resulting in one fatality each. Both times, there was no prior warning because the storms were being tracked by the closest doppler radar, in Norman, which could not detect the low-altitude storms from that distance.

“We couldn’t see it coming,” said Sen. David Bullard (R-Durant).

Bullard assembled a task force that ultimately decided to pursue the installation of a local radar system, and last year Durant received a $1.6 million grant from the state to install a system that will cover an 85-mile radius. The project is slated for completion by July.

Not all coverage issues can be solved with a state grant and homegrown infrastructure, however. When it comes to news coverage, an evolving media landscape and government policies leave many border counties stranded from the rest of a state. As a result, while many residents pay attention to local and national issues, access to state news coverage is fraying, and with it goes civic knowledge and engagement.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

‘We don’t have a lot of choice’

In Hot Shots Coffee, a popular spot in Durant, stacks of crisply folded copies of The Durant Democrat — dated 10 days prior — lie unread on the bar. Across the country, fewer people are reading local newspapers than ever before, and Durant is no different. TV dominates the news landscape, as it does in much of the rest of the country.

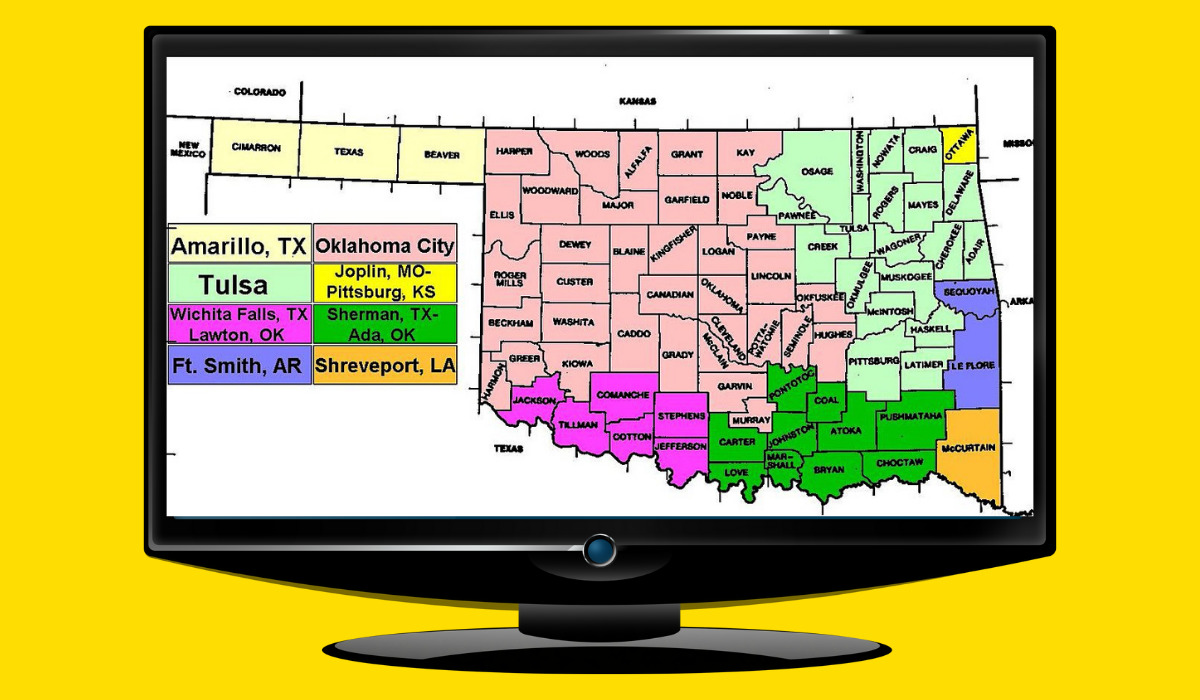

Federal policies have defined television market zones that cut across state lines, swallowing up parts of Oklahoma into markets centered on larger Texas or Louisiana cities. Bryan, Choctaw and McCurtain counties, situated at the southeast edge of Oklahoma, know this problem well.

“We’re in one of those areas where we’re physically closer to out-of-state TV providers than Oklahoma TV providers. It seems like it’s not going to change as far as broadcast TV,” said Pete Wilson, who runs The Valliant Leader, a small newspaper in McCurtain County.

TV news coverage of Bryan County arrives through Texas-based news channels KTEN and KXII. According to Bullard, both stations do a “decent job” of balancing between their Oklahoma and Texas audiences and across urban and rural divides.

RELATED

Direct text: A new way to receive NonDoc’s top stories by Kylie Hushbeck

When it comes to the statewide news of Oklahoma, however, Bullard said very little reaches the area. Bryan County receives no Oklahoma-based TV channels — even the OETA Oklahoma News Report, which airs on PBS, was unavailable on the TV in a Durant motel — and larger newspapers such as The Oklahoman would have to be delivered by mail.

KTEN and KXII describe their coverage area as the “Texoma” region, and they do cover issues in Bryan County, Choctaw County and the Choctaw Nation. This partial coverage is more than what some communities have.

In the town of Valliant, just four miles outside Choctaw County, available TV news stations are broadcasted from Shreveport, Louisiana, and serve the “ArkLaTex” region — Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas. Although, according to Wilson, bad news in McCurtain County sometimes draws the stations’ attention.

“They don’t even include Oklahoma, but still that’s what we’re forced to watch,” Wilson said.

At 71, Wilson has worked in the newspaper business for more than 50 years. He and his wife run the Valliant Leader, occasionally contracting out photography and reporting but providing most of the content themselves. The paper has 1,600 paid subscribers — nearly twice the population of Valliant, where the Leader is the only source of local news.

“We don’t have a lot of choice as to what’s available to us,” said Wilson.

Wilson recalled that McCurtain County used to receive state TV news, but he said that access has disappeared under changes to FCC rules and consolidations in the industry. According to Wilson, the advent of satellite TV caused small-town cable companies to go out of business. And even satellite companies like DIRECTV restrict access to certain local stations to subscribers within the station’s broadcast area.

“We’re hungry for Oklahoma news,” Wilson said. “Not just me, but most people in our area. We’re Oklahomans, and we like to have Oklahoma news available to us.”

Wilson and others have tried to get various levels of government to address the situation, but with no luck so far.

“Several years ago, we tried to work with our elected officials, state and national office holders, to try to get the satellite companies to give us more Oklahoma news channels. They never were able to get anything done about it,” Wilson recalled.

These days, Wilson battles one main competitor for readership: Facebook. Social media platforms, and particularly Facebook, have emerged as a tempting source of news for young and old alike in rural communities.

Wilson pointed out that the information on social media platforms can be unreliable.

“So much of what I see on Facebook is just either factually incorrect or it’s very slanted politically, so I think it lacks a lot in that regard,” he said.

The situation has spurred some innovative approaches to news coverage. Joey McWilliams, a Durant resident, runs a one-man, online-only news service, the Bryan County Patriot, which he said focuses on the positive aspects of life in Bryan County.

The Patriot covers local businesses, school events and uplifting news that McWilliams believes other outlets sometimes neglect.

“The local newspaper has gone from a daily paper to once a week,” he said. “It was under different ownership then, but it needed competition. There are enough stories to go around in Bryan County.”

McWilliams, who has a background in sports broadcasting and religious ministry, started The Patriot in 2017. He has been running it full-time since, while still contributing to a sports news website he founded in 2011, oklahomasports.net.

“I am the Bryan County Patriot,” he joked.

McWilliams uses the platform to post YouTube Live videos of interviews with influential community members, coverage of local sports teams and (mostly) encouraging news stories. The publication has received enough engagement that McWilliams plans to establish an affiliate in Marshall County.

“Granted, I do have some car wreck stories on YouTube. Those get the real traffic, but it’s the positives I try to promote,” he said. “We hear so much that is negative and fear-based because it gets more viewership. I’m actively looking to promote the positive to prevent people from walking in fear. You can walk in respect with wisdom in a situation and not walk in fear.”

‘The only time you get involved is when it’s already impacted you’

Social media, plus the availability of national news networks like Fox, tend to keep citizens informed on national issues. When asked, a number of residents of varying ages in the overwhelmingly conservative region said they feel they had a satisfactory grasp of candidates and politicians in the 2020 and 2016 presidential elections to make informed decisions. Bullard was optimistic about voter turnout in recent elections, despite Oklahoma’s lagging numbers compared to the rest of the country in that regard.

Bullard struggles to encourage his constituents to care about local and state politics, however.

“Getting people to engage in local issues is really low. Usually, the only time you get involved is when it’s already impacted you,” he said. “Most of your news, they’re tuned in because it’s weather-related.”

Though some community leaders and politicians voiced frustration with what they perceive to be bias among media, everyday citizens seemed less concerned about bias than about maintaining a level head amid an overwhelming torrent of information, much of it discouraging.

RELATED

Hey, newspapers: Free NonDoc content for your print product by Tres Savage

At the Hot Shots coffee shop, a woman named Gemma who works as a graphic designer at KTEN, said she believes too much news consumption can be unhealthy.

“I try to stay away from it because it’s easy for us to get consumed by everything that we hear,” she said, pausing from a card game with her father. “Sometimes that can mess with our fears and nerves.”

Others avoid news consumption because they dislike the vituperative atmosphere present in much of the American news media.

A college student named Madison, talking after a meeting at First Baptist Church of Durant, said she tends to avoid consuming news from any source.

“I’m non-confrontational,” she explained.

She said she realizes that not taking in the news affects her civic participation.

“I didn’t even know what midterms were,” she continued. “But I think I would be more likely to vote if there was more coverage.”

Her friend, Sarah, chimed in: “I don’t feel like I’m informed enough to be engaged.”

Between boundaries

Wilson said being in the zones of Oklahoma-based media affiliates would help increase news coverage and the diversity of perspectives available to citizens, but, more importantly, it would ameliorate his constituents’ sense of being disconnected from the rest of Oklahoma.

McCurtain County residents pursue information for themselves, he said, even if that information may filter through Facebook’s opaque algorithm system. Cable news and social media keep residents informed of national issues and, to a much lesser degree, issues facing the state of Oklahoma as well.

RELATED

Hochatown: Southeast Oklahoma’s unlikely tourism hub by Heide Brandes

Rep. Eddy Dempsey (R-Idabel) has a more dire outlook.

“My part of the world doesn’t have a clue,” he said of what goes on at the State Capitol.

For Wilson, better local coverage would help people feel “more included in what’s going on across the state.” Those located in southeastern Oklahoma, so close to the borders of Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana, often feel as if they do not belong to Oklahoma at all — and as if legislators in the State Capitol overlook rural communities to whom they are or feel less accountable.

At the coffee shop, Sarah and Madison corroborated the sentiment, saying they see themselves more as residents of Texas than Oklahoma.

“Especially during COVID, what was going on in Texas was more important, even nationally, than what was going on in [Oklahoma] City,” Sarah said.

Dempsey recalled how the Oklahoma Department of Transportation attempted to implement a new policy in Norman, home to the University of Oklahoma. The department met opposition from the public and the local media. He said he wished that issues in his district received the same attention.

“News stations blew it up,” he remembered. “If they would come [to McCurtain] and have a news station interview everyone, that would help me tremendously to fight some of these battles with state agencies.

“We should not be handicapped for a marketing area that used to be when we only had antennas. That’s all it boils down to. It just hasn’t been updated.”

(Correction: This article was updated at 9:40 a.m. Thursday, June 2, to remove an incorrect reference to the broadcast media landscape in southeast Oklahoma. It was updated again to correct the name of The Durant Democrat.)