When Wayne Frost purchased a plot of land next to his auto accessory business in Edmond, he knew his neighbors might protest his business expansion. What he did not know, however, was that the plat on the property included a racially restrictive covenant, which historically allowed only white people or Native Americans to own the land.

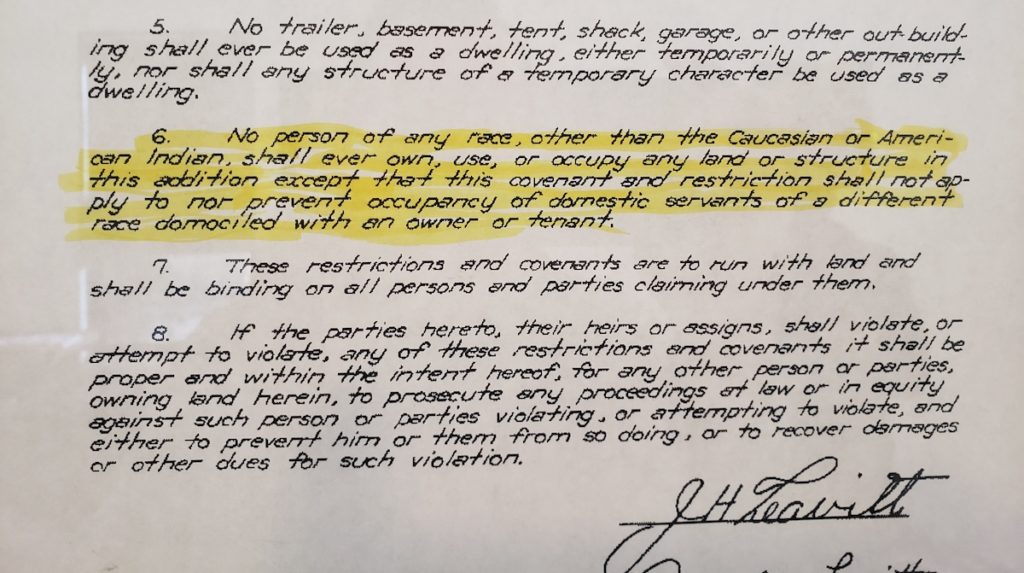

Although unenforceable now, restriction No. 6 of the Leavitt’s North Park Addition plat for Frost’s new property is blunt:

No person of any race, other than the Caucasian or American Indian shall ever own, use, or occupy any land or structure in this addition except that this covenant and restriction shall not apply to nor prevent occupancy of domestic servants of a different race domociled (sic) with an owner or tenant.

Frost — a Black man — said he was shocked to read the passage. As he worked his way through a cycle of emotions, Frost decided to highlight the racially restrictive covenant and hang the document on the wall of a lounge room within his business, located at 4646 Rhode Island Ave.

“People are always telling me there’s no such thing as white privilege or things like that,” Frost said. “It’s just a reminder for me of where we’ve come from, from where this place used to be in the ’50s, to what it is now.”

When the land plat was signed in 1947, Edmond was widely recognized as a sundown town, meaning Black people faced intimidation and threats for being visible in the community after sunset.

“When you look at the demographics of other towns around Edmond and the activity going on with KKK at the time, there’s just little doubt [it was a sundown town],” said Amy Stephens director of the Edmond Historical Society & Museum.

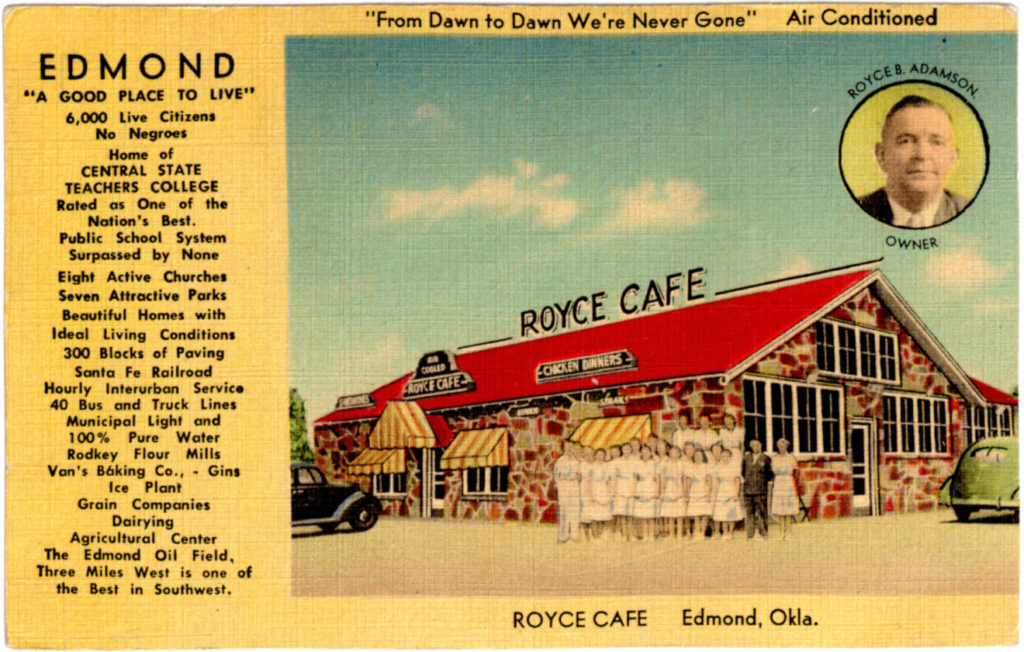

In the 1920’s, articles published in the Edmond Sun and the Edmond Enterprise promoted Edmond as an all-white town, according to the historical society. A popular Edmond restaurant that stayed open from 1934 to 1970, the Royce Cafe, promoted Edmond’s demographic makeup on a postcard, stating, “6,000 Live Citizens No Negroes.”

Edmond’s first housing addition platted with a racially restrictive covenant was the Highland Park Addition in 1907. Excluding the Edmond Highway Addition in 1924, every neighborhood platted in Edmond from 1911 until 1949 contained a racially restrictive covenant.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelly v. Kraemer that enforcement of discriminatory covenants based on race violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

That legal precedent was codified into law 20 years later on April 11, 1968, when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act, just seven days after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.

While racially restrictive covenants are legally unenforceable today, Frost said the language in his property’s plat is still upsetting for Black Edmondites.

“It is discouraging,” Frost said. “I can’t believe it’s still on the books after all these years.”

Addressing racially restrictive covenants across the U.S.

Jeremy Yohe, vice president of communications at the national American Land Title Association, said title companies have worked to remove racially restrictive covenants when they are discovered in title searches, but they are still commonly found in land records.

“During the 20th century, discriminatory restrictive covenants peppered property records in communities across the country,” Yohe wrote in a 2021 article on the issue. “In Minneapolis, the first racial covenant appeared in 1910, when Henry and Leonora Scott sold a property to Nels Anderson. The deed conveyed in that transaction contained what would become a common restriction, stipulating that the ‘premises shall not at any time be conveyed, mortgaged or leased to any person or persons of Chinese, Japanese, Moorish, Turkish, Negro, Mongolian or African blood or descent.'”

Yohe said title companies across the country have taken actions on racially restrictive covenants, such as simply crossing out the covenant or blanking out the covenant and stating “this covenant omitted.”

But expunging racially restrictive covenants can be problematic, as it impacts property rights and the chain of title on affected properties, Yohe said.

With no national uniform measure to address such covenants, some lawmakers have taken action. U.S. Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.) introduced a bill in July 2021 that would create a competitive grant program for educational institutions that work to identify such covenants. The bill would fund local governments to digitize these public records, with the purpose of recognizing communities that were affected decades ago by the enforcement of racially restrictive covenants.

The bill was introduced and referred to the Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, but it has received no action since.

At the state level, the Texas Legislature passed a 2021 bill into law that provides a mechanism for judges to remove discriminatory covenants based on race, color, religion or national origin from land deeds via an order from the property owner.

Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis have also signed legislation to address these issues in different ways.

Edmond Ward 2 Councilman Josh Moore said he is unsure what course of action the city could take to address the issue at the municipal level, but he said he would support an effort to expunge discriminatory covenants from the the City of Edmond’s public land records.

“I’m not a legal expert on title language across the board, but I would be in complete favor [of expunging racially restrictive covenants],” Moore said. “In a perfect world for me, we would figure out a way to remove it all.”

Darrell Davis became Edmond’s first Black mayor when he was elected in 2021. NonDoc asked Davis whether he would support some sort of action to remove racially restrictive covenant language from Edmond property plats, but City of Edmond marketing and public relations manager Bill Begley responded to the question and said, “The mayor isn’t going to comment on this today.”

Instead, Begley provided his own statement.

“I can say unequivocally the language found in some historical documents and records does not represent the Edmond of today. Our city is an inclusive city that welcomes all,” Begley said.

Frost vs. Leavitt’s North Park neighbors

When Frost bought his original property on Rhode Island Avenue in 2016, Leavitt’s North Park neighbors opposed his business being built facing Memorial Road.

A plat restriction within the neighborhood provides that “all lots shall be known and described as residential property and no structure shall be erected, altered, placed or permitted to remain on any lot, other than one detached single-family dwelling and structures customarily appurtenant thereto.”

Now, Frost has purchased the abutting property just north of his business in hopes of constructing a commercial storage building to house boats, recreational vehicles and automobiles.

Frost requested to rezone the newly purchased property from a single-family residential dwelling to a planned unit development, which would allow the construction of his proposed storage unit. The Edmond Plan 2018 designates the area as a suburban neighborhood, which recommends planned unit development zoning for anything not residential.

Frost went before the Edmond City Council at a Jan. 10 meeting, but after hearing grievances regarding commercial intrusion from Leavitt’s North Park neighbors, councilmembers voted unanimously to delay the item for a later meeting.

“What he has proposed is, in fact, an RV and boat, outside and covered parking lot. I don’t know anybody who wants such a parking lot in their neighborhood,” said Thomas Squires, an area neighbor said at the Jan. 10 meeting.

The Edmond Planning Commission previously recommended approval of Frost’s rezoning request by a narrow 3-2 vote during a Dec. 7 meeting, with planning commission members and neighbors citing concerns about commercial intrusion into the neighborhood.

But Frost argues that some neighbors are already operating a business in the area.

“Right across the street they have just built two metal buildings that are commercial. Inside the neighborhood like three doors down to the north of me, there is dump trucks coming in and out of there,” Frost said. “So it’s very visible that it’s a business, and no one has said anything about it.”

Squires admitted during the Dec. 7 planning commission meeting there is some commercial action ongoing in the neighborhood, but wants to stop that activity as well.

“There has been some talk about some businesses being run there, and clearly that is happening and it is a zone infraction, for sure,” Squires told the planning commission. “We need to do something about that. It’s not that it should be going on at all, or in any way allowed in our neighborhood.”

During its January meeting, the Edmond City Council discussed whether Frost’s zoning request is proper for the type of use he is intending, as well as the accompanying setback that is required when a commercially zoned land plot is abutted against a residentially zoned plot.

When a planned unit development is zoned next to a residential zoning, it creates a “sensitive border,” which means the building on the planned unit development property must be setback 10 feet from the residential property.

Asked by Moore, the Ward 2 councilman, what the appropriate zoning on the property would be if it were not requested by Frost to be zoned a planned unit development, Randy Entz, the City of Edmond’s director of planning and zoning, said it would be zoned E-1, for industrial use. Entz said an E-1 zoning type would require a 70-foot setback from the abutting residential property’s sensitive border — a variance from the 10-foot setback required of Frost’s requested planned unit development.

However, after further pressure from the Leavitt’s North Park neighbors, Frost said he has decided to forgo building any property on his newly purchased lot.

Instead, he is now planning to ask Edmond officials for approval to build a storage facility on the north side of his original lot at 4646 Rhode Island Ave. That property already has commercial zoning and would likely erase issues regarding setback distance from the neighborhood’s residential property, as the closest property to Frost’s proposed storage unit is his newly purchased property.

Frost said he is planning to submit the site plan application in the coming weeks. He will have to receive approval from the Edmond Planning Commission prior to going before Edmond City Council.

(Correction: This article was updated at 5:15 p.m. Friday, July 8, to correct a mistake confusing title work and land records. NonDoc regrets this error.)