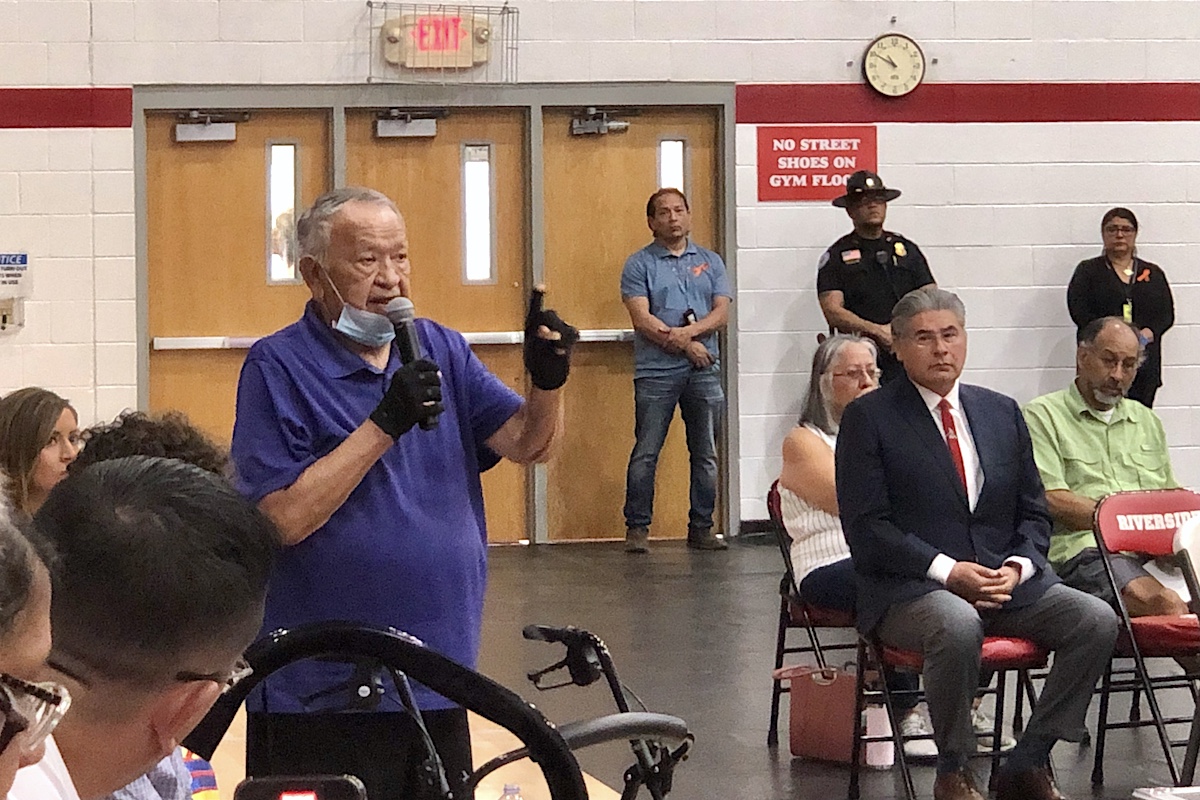

ANADARKO — Standing among about 300 people this morning in the Riverside Indian School gymnasium, Donald Neconie told federal officials, tribal leaders, tribal citizens and media about his experiences at the Indian boarding school from 1946 to 1958.

With a mask pulled below his chin and one hand on his walker, the 84-year-old Neconie described the abuse and mental anguish that generations of Indigenous children endured at hundreds of federal boarding schools across the country, which originally attempted to disconnect students from tribal cultures and assimilate them into American ways.

“Those days, I can remember going home only twice,” Neconie said. “I spent 12 years in this hell-hole, and that’s what it was like: Hell.”

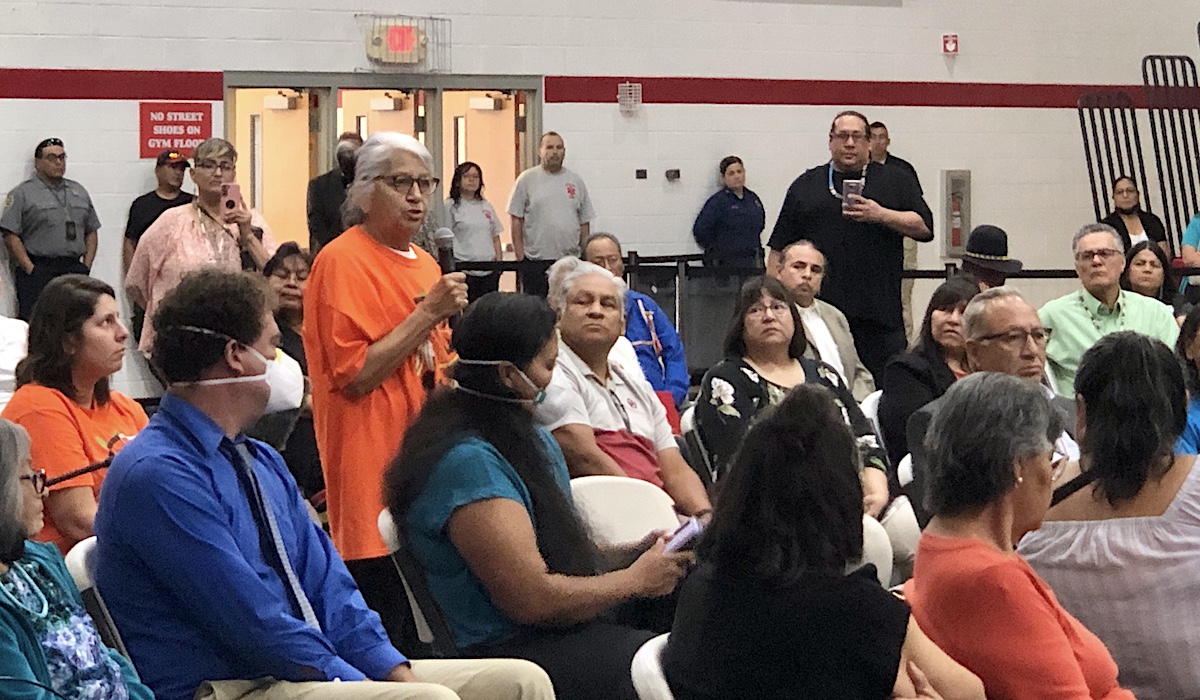

Neconie told his story during the first stop of U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland’s “Road to Healing” listening tour, which aims to chronicle the stories of Indian boarding school survivors and foster reconciliation for tribal citizens.

“Through this effort, we want to not only create a platform for people to share, but also to help connect communities with trauma-informed support and facilitate the collection of a permanent oral history,” Haaland told attendees. “I want you all to know that I am with you on this journey, and I am here to listen.”

Haaland, a former New Mexico congresswoman who became the first tribal citizen to serve as secretary of the interior, declined to speak with media during or after Saturday’s event. She did open the day’s conversation with brief remarks.

“As we mourn what we have lost, please note we still have so much to gain. The healing that can help our communities will not be done overnight, but it will be done,” Haaland said. “This is one step among many that we will take to strengthen and rebuild the bonds with the Native communities that federal Indian boarding schools set out to break. Those steps have the potential to alter the course of our future.”

‘It may be good now, but it wasn’t back then’

Situated along the north edge of Anadarko and the Wichita, Caddo and Delaware nations, Riverside Indian School is the oldest and largest off-reservation boarding school in the Bureau of Indian Education system. The modern school — located near the historic school grounds — is generally viewed as a positive institution that serves hundreds of students from dozens of tribes.

James Nells, a full-blood Navajo citizen who graduated from Riverside in 1977, led the color guard procession at the start of Saturday’s event.

“I think Riverside is a very good school, and it is helping a lot of the underprivileged students and families,” said Nells, who now teaches native song and dance and coaches cross country at Riverside. “When I graduated from boarding school, I went on to college. That’s the same opportunity we give these kids, so it’s all good right now. But, in the past, there has been a lot of wrong that has been done to Native Americans. That was back then. Now we’ve changed and are hopefully making things better.

“I think that we have a very good administrative staff here helping out the children.”

But Nells’ experience as a student then and his values as an educator now were not reflected in the memories of many students who attended federal Indian boarding schools decades before him.

Neconie bluntly reminded the gymnasium’s crowd of that when it was time to tell his story.

“We were sodomized. Men, girls, boys. We were sodomized, and people knew that was going on, and they did nothing,” Neconie said, adding that federal officials visited the school during his time there. “They didn’t do anything to those people, and we went through hell again because we were told if you told anybody you would have the hell beat out of you.”

Neconie said the sexual abuse stopped “for some reason” in the 11th grade, but the effects haunted students for the rest of their lives.

“I still feel that pain. I still feel what this school did to me,” Neconie said. “I don’t care how much money it takes, I will never, ever forgive this school.”

Neconie also described abusive intake processes and efforts to break him of his native tongue at the neighboring St. Patrick’s Mission, which he attended before landing at Riverside.

“I used to talk Kiowa. I understood it,” Neconie recalled. “But after what they did to me, every time I tried to talk Kiowa they put lye in my mouth. They washed my mouth.”

He said he would like an apology from Riverside officials, even though administrators from his time at the school are long gone.

“I’m not going to sugarcoat this Riverside Indian School. It may be good now, but it wasn’t back then,” Neconie said. “When they tore down Kiowa Lodge, I stood by and cheered.”

When Neconie concluded his powerful remarks, five quiet drum beats underscored the solemn nature of his comments.

‘They gave me a number, and my number was 199’

The first hour or so of Saturday’s event was open to media, with dozens of news outlets attending to chronicle stories and report on the Department of the Interior’s investigative report about federal Indian boarding schools that was released in May. Following a brief break, the day’s listening session continued without the presence of journalists for those who wished to tell their stories in a more private setting.

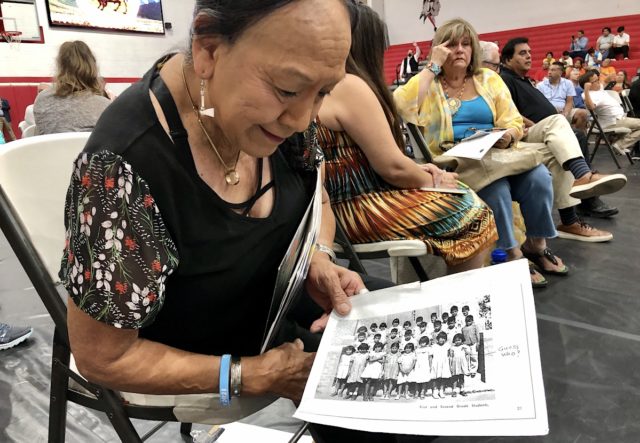

During the morning portion, a Standing Rock Sioux artist named Brought Plenty described her experiences at the Pierre and Eagle Bute boarding schools in South Dakota. Like most of the elders who spoke of mistreatment Saturday, Plenty described the cutting of hair, shaving of heads and use of burning chemicals that constituted the schools’ student intake process.

“They told me I was no longer able to use my name. They gave me a number, and my number was 199,” Plenty said. “We were not allowed to speak unless spoken to. I was punished a lot because I did talk. We were not allowed to talk our language or speak our language.”

She said school staff asked whether she wanted to be Catholic or Episcopalian, and she said she thought the two religions were the same.

“They put a metal cross in my hand and told me I was going to be an Episcopalian and to go pray for forgiveness of who I was,” Plenty said.

Plenty described beatings, whippings and “terrible” actions — “cutting your hair off and throwing it in your face” — and said she has been in counseling since age 22.

“What they did to us makes you feel so inferior that you don’t feel worthy of anything. I didn’t even think I was worthy of going to college,” Plenty said. “To this date, I have counseling twice a week, and you never get past this. You never forget it. What they did to us was terrible. I don’t know how we survived. But I always tell myself and tell our children, those who didn’t get to come home, it is time to bring them home.”

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

‘It’s unconscionable the things that were done’

Chickasaw Nation Gov. Bill Anoatubby sat in the front row of Saturday’s listening session, greeting Haaland briefly during the break and turning around in his chair several times to see federal Indian boarding school survivors stand and recount their experiences.

“I think they’ve used the right word when they say ‘survivors,’ because these people did survive some terrible things that happened to them,” Anoatubby said during the event’s break. “But the tribes themselves suffered because our people going through these things (…) it affected us. A lot of the things like our language, our traditions and our culture, they were trying to wipe us out. And they got really close in some tribes.”

Anoattuby said “we’ve come a long way” in terms of relations between the U.S. government and tribal nations, and he praised Haaland’s efforts to chronicle the stories told Saturday.

“We’ve heard these accounts for decades of the kinds of things that occurred. It’s really heart-wrenching to hear it from the people who really experienced it,” Anoatubby said. “It’s unconscionable the things that were done, and while you can’t go back and you can’t fix what happened, we can make things better, and we can help people around us understand that what happened was not right.”

Anoatubby said the Chickasaw Nation has worked hard to “recapture our language” and create its cultural center for the edification of tribal citizens and non-tribal citizens alike.

“Some tribes held on and held on, and it didn’t really affect them as severely. But some tribes almost lost their language. Some tribes had moved away from their traditions and their culture, so they were almost done away with,” Anoatubby said. “When you acculturate a group, that group ceases to exist, and a lot of us got really close.”

Muscogee Nation Principal Chief David Hill also attended Haaland’s event and praised her leadership.

“She is in that position where she can help all native people,” Hill said.

He said the morning’s stories were heavy.

“It’s really devastating to hear all of that because I never experienced that personally — boarding school,” he said. “But I do remember I could not speak English in the first grade or the second grade.”

With his parents working all day, Hill said his cultural experience shifted in school.

“My English started dominating my Creek language,” he recalled.

Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe, spoke during the morning session and said he came “bearing the testimony of one of my tribal citizens who could not be here.”

RELATED

Lack of records confounds school cemetery’s history by Stephen Martin

Barnes described boarding schools as the “chosen weapon” to attack tribal cultures and communities for more than 100 years, and he took Haaland up on her request for policy suggestions.

Barnes said the land of closed Indian boarding schools should be offered back to sovereign nations, and he said careful consideration should be given to the location of current and future housing developments for elders who attended boarding schools.

“They don’t want to live anywhere close to the location of their rape,” Barnes said.

Barnes also posited a question pertinent to Riverside itself: “Why is it that Indian boarding schools are the only ones with cemeteries?”

At least one school cemetery exists near Riverside. Owing to a lack of records, however, no one knows for certain how many children have been buried there since the school opened in 1871, nor do they know exactly where all the graves are located.

NonDoc reported on the issue in 2016. Asked if the Department of the Interior had any new information or plans regarding the unidentified Riverside cemetery, Haaland’s press secretary, Tyler Cherry, said the federal agency does not have an update on the situation.

Plenty, who lives in Dallas, said she and her daughter purchased a ground-penetrating radar device to assist tribal communities in their search for Indian boarding school gravesites.

“We are ready to help,” said Plenty, who noted she brought the machine with her to the Riverside event.

Another speaker during the morning portion of Saturday’s event was Delores Twohatchet, a Kiowa and Comanche woman who described her experiences at Fort Sill Indian School near Lawton.

“In spite of the difficulties, I managed to survive and became an honor student, even though I was teased by the other children,” Twohatchet said, fighting back tears as she spoke. “I think the most traumatic (thing) about me is they cut off my hair, so that is why I wear my hair long.”

Twohatchet walked to the front of the gymnasium and gifted Haaland a hand-made shawl, wrapping the federal cabinet member in the garment and thanking her for raising awareness of boarding school history.

“We need to tell what happened,” Twohatchet said.