Now is the time to commit to cross-generational conversations, with Baby Boomers listening to Millennials and Gen Z-ers and sharing our experiences from the 1960s and 1970s.

Prairie Power: Student Activism, Counterculture, and Backlash in Oklahoma 1962-1972, by Sarah Janda, provides a wonderful opportunity for such a dialogue. It tells the story of what was happening in Oklahoma during one of the most heated periods of protest in American history and points to potential strategies for the future.

Even though I was born in 1953, the middle of the Baby Boom, I learned much from Janda’s book, particularly about students who were just a few years older than me and why they deserved the title of “Prairie Power.”

Janda also reinforced my long-held belief that the rebels she describes were linked to Oklahoma’s earlier traditions of radicalism. And she made me wonder, not for the first time, how my generation would have responded to Jim Crow, sexism, illegal monitoring by state and federal authorities of anti-war activists, and right-wing aggression if we had been taught a balanced history of Oklahoma populism, socialism and civil rights.

Enemies in high places

For the most part, student activism and the counterculture in the 1960s centered on the University of Oklahoma. (Sadly, Oklahoma State University’s leadership was cowed into supporting even the most illegal surveillance and censorship that was demanded by the state. Though, during a brief period connected with protests in Norman, OSU students pushed back strenuously, and sometimes many of the top ACLU/OK leaders and criminal law reformers were based in Stillwater.)

Contrary to the assumptions of so many Oklahomans at the time, few of these students were extremists. The Students for Democratic Society (SDS) were mostly closer to reform-minded liberals than radicals. Anti-war, anti-draft and civil rights activists were not Communists. Hippies and other believers in the counterculture movements were resisting the superficiality of American consumerism. They took on causes such as desegregating the bathrooms at the Cleveland County Courthouse (at the urging of Clara Luper) and inviting political speakers to campus. Nevertheless, they attracted enemies.

Backed by the anti-Communist hysteria of the times, as manifested in McCarthyism and the “little Dies committee” created by the Oklahoma Senate to root out communists from government and universities, the “law and order” crowd sought to censor these activists.

For instance, in 1969, a publication called the Jones Family Grandchildren (named after left-wing World War I resisters) published a satirical cartoon of police officers sexually assaulting the Statue of Liberty. It mostly showed intertwined arms and legs, but the pornography law had been changed to include “any” book, drawing or picture as illegal “if it is offensive to the modesty or chastity,” or if it is “something that purity and decency forbids.” The five staff members were charged with a felony that could have cost a combined fine of $25,000 and 15 years each in prison.

When OSU tried to invite speakers like Thomas Altizer, Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary, U.S. Rep. Adam Clayton Powell and Abbie Hoffman, conservative attacks became more vociferous. As OSU sought to use the concept of “in loco parentis” to control students and limit free speech, parents condemned such speakers and labeled the students who listened to them as anti-American, treasonous, dupes and dopers.

Widespread surveillance

The measures taken to quash student activism were extensive. Counter-intelligence agencies distributed fake newsletters, supposedly by campus radicals. Another tactic was sending anonymous letters to parents whose children had supposedly been involved in the SDS, attacking the organization for immorality, subversion and drug use.

Also, a combination of police department “red squads,” the FBI’s COINTELPRO operation, the Justice Department, the military and the Oklahoma Office of Interagency Coordination (OIC) ramped up a coordinated but clumsy series of illegal surveillance campaigns against students. I suspect the story that today’s readers will find most interesting in Janda’s book will be the FBI wiretapping the yippie Abbie Hoffman in Stillwater while, in the same hotel, the Oklahoma City police wiretapped his ACLU lawyer, Stephen Jones.

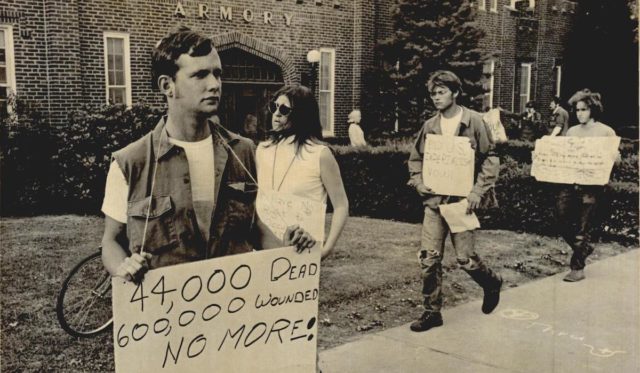

Federal and state agencies cooperated in targeting anti-Vietnam War protesters and draft resistors. They often sought to expel students for dubious or false reasons (such as supposedly not paying interest on a student loan, even though the payments had been made) so they could be drafted. The 112th Military Intelligence (MI) Group photographed and collected files on students for transgressions like circulating handbills, and the MI shared them with multiple agencies, including the FBI, the police and the OIC.

In 1968, 28 demonstrators were arrested for protesting Gen. Lewis Hershey’s draft rules, designed to punish anti-war students. All were acquitted, but federal and state surveillance continued to increase.

The FBI’s widespread surveillance continued as radicalism declined. Under the administration of Oklahoma Gov. Dewey Bartlett, the OIC surveilled three categories of activists: “radical,” “anti-war, anti-draft, anti-military” and “general.” It kept files on the Comanche activist LaDonna Harris, the wife of Sen. Fred Harris, and on Oklahomans for Indian Opportunity, which she founded. It also had files on the Five Tribes Council, the Oklahoma City National Welfare Rights Group, and other peaceful organizations. And it monitored activities such as “gentle Thursday” on the South Oval at OU.

The end of an era

The tensions of that era never quite boiled over in Oklahoma, thanks to specific decisions by leaders and activists.

As the nation’s universities erupted after the killings of unarmed protesters at Kent State in 1970, even OU could have been caught up by violent protests. But, in contrast with OSU, officials in Norman developed more cooperative and balanced approaches to activism. Bartlett wanted to intervene using armed agents, but local authorities pushed back, seeking peaceful means to avoid escalation. For instance, professors like David Levy, in OU’s history department, served as peace marshals. And, sure enough, an officer lost his gun during a protest, but a demonstrator found it and returned it to the police.

Gov. David Hall, who won election in 1974, compared the OIC, which he called the “Sooner Snooper Group,” to the Gestapo. He burned the more than 6,000 files the agency had kept on Oklahomans it was monitoring.

As the drama of the ’60s and early ’70s declined, young people seeking justice and progress committed to more low-key efforts to build a better and sustainable world. One example was Tempie and Fenton Rood, who opened The Earth Natural Food Stores. Others brought their lifestyle into the countryside or small towns, or to liberal churches or yoga retreats and drum circles.

Janda concludes that these movements sought “to seek truth and debate controversial ideas.” Their rebellion was rooted in lessons from various Oklahoma movements and leaders, ranging from evangelism to the socialist Oscar Ameringer and Woody Guthrie, as well as civil rights and women’s rights activism. They sought to pass on a more authentic world.

And that raises the question: If histories such as Prairie Power were read in school, and discussed by the coming generations, couldn’t we build on the best of Oklahoma’s countercultures?