In June, Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater filed criminal charges against the founders and former chief financial officer of Epic Charter Schools, dramatically advancing a case that took nearly a decade to investigate and that involves a web of political powerbrokers.

In a matter of days or weeks, however, Prater is expected to announce his charging decisions regarding financial problems at another charter school that involved politically powerful Oklahomans.

The Justice Alma Wilson Seeworth Academy closed in 2019 after the State Department of Education found the school to be “seriously deficient in the areas of transparency, accountability and policies and procedures as they related to the school’s federal funds.” OSDE requested a special investigative audit from State Auditor & Inspector Cindy Byrd.

Released in November, the state audit detailed significant findings and added meat to the bones of a criminal investigation. Auditors discovered evidence and allegations that:

- Seeworth’s longtime superintendent, Janet Grigg, embezzled funds for a decade, took unauthorized bonuses, once paid her home mortgage with school dollars and terminated employees who questioned her financial management;

- Seeworth’s influential board of directors — which featured Oklahoma Court of Civil Appeals Judge Barbara Swinton and Senate Minority Leader Kay Floyd (D-OKC) — repeatedly disregarded reports about the superintendent’s behavior;

- Various board members settled a 2012 discrimination lawsuit brought by a terminated former principal, scoffed at a concerning 2008-2009 internal audit and voted during a “30-second meeting” to remove a board member who had asked questions about a whistleblower letter;

- Seeworth Academy board members authorized and/or allowed expenditure of school funds after officially relinquishing the school’s charter on June 30, 2019.

Beyond the embezzlement and “fraud” allegations against Grigg, auditors alleged that some actions by the school’s board constitute violations of state law. Prater has been investigating whether those actions rise to the level of criminal charges, particularly as it relates to the expenditure of school funds after board members voted to close the school.

“The theft or the misappropriation of money that was intended to benefit our state’s children is a serious matter to me,” Prater told NonDoc in November when the Seeworth audit was released.

Since, Prater has declined to elaborate on his inquiry, but audit work papers and a new interview with Floyd — the top Democrat in the Oklahoma State Senate — shed light on Prater’s potential prosecutorial decisions.

Audit: Grigg spent thousands on shopping, casinos

In their report, state auditors said Seeworth Academy Superintendent Janet Grigg “misappropriated” more than $250,000 of school funds, $41,000 of which came from a “corporate account” that was opened under the school’s name but was not included in audited financial statements. In their interviews with state auditors, Seeworth board members claimed various levels of ignorance about the corporate account’s origins and records.

“The fraud consisted of improper ATM cash withdrawals, improper debit card purchases, and improper checks,” state auditors wrote. “Almost $10,000 was spent with QVC, HSN, and Evine, online retailers. Of the $4,500 in ATM withdrawals, over $2,200 was made at a local casino. Over $15,000 consisted of checks made out to Grigg or to cash. The remaining $11,500 were additional debit card transactions which included charges and cash withdrawals at Dillards, PayPal, Priceline, and various local convenience stores.”

RELATED

Whistleblower letter, booting of board member raise Seeworth Academy oversight concerns by Tres Savage

An alternative school founded in 1998 to serve at-risk youth who had been affected by the criminal justice system, Seeworth Academy was named after former Oklahoma Supreme Court Justice Alma Wilson, the mother of board member Lee Anne Wilson.

Seeworth Academy became a charter authorized by OKCPS. Charter schools are public schools that receive taxpayer funding, feature their own governance board and retain responsibility to meet proper state and federal reporting requirements.

Charter school boards are legally tasked with oversight of a school’s finances and its superintendent. State auditors found that the Seeworth board — particularly longtime members Swinton, Floyd and Wilson — had received warnings, reports and recommendations for years regarding Grigg’s fiscal management and alleged gambling problem.

“Despite the fact that financial and internal control issues, along with red flags for potential fraud, were brought to the attention of the board, they failed to initiate follow-up procedures, increase oversight, or take other appropriate measures,” auditors wrote. “In March 2019, when the board received a whistleblower letter alleging financial improprieties, the allegations were dismissed. Soon after, when an individual offered to donate $1 million on the condition that an independent accounting firm conduct an audit of Seeworth, the donation was refused. (…) The overarching lack of oversight by the board created an environment ripe for financial mismanagement and the misappropriation of funds.”

In his interview with state auditors, former Seeworth principal Mongo Allen said Floyd, Swinton and Wilson “knew what was going on” with school finances. Allen was fired by Grigg, whom he described as “a James Bond villain,” and he sued the school.

Allen’s 2012 lawsuit was settled, and he has declined NonDoc interview requests. Swinton has told NonDoc it would be inappropriate to discuss Allen’s lawsuit. Floyd said she had no recollection of Allen’s allegations that Grigg shredded financial records in front of him, spent school hours at a casino and mishandled money raised from sporting events.

In his interview with state auditors, however, Allen found that assertion laughable.

“Everybody needs to know that this board is negligent. (…) They’re negligent because they sat back and allowed this to happen, again, and even though they fired her, they knew this [stuff] was going on,” Allen told auditors. “Lee Anne Wilson and Barbara Swinton — and those were the two heavies that have been consistent — they knew.

“There’s no reason why they should be allowed to get away with what they did.”

‘Inappropriate expenditures’ made after school closed

Despite Allen’s warnings and his 2012 lawsuit, Seeworth Academy rolled on for another seven years under the direction of Grigg and the oversight of Swinton, Wilson, Floyd and other board members.

But that changed in 2019 with the OSDE inquiry and a report to the Oklahoma City Police Department by Oklahoma City Public Schools Superintendent Sean McDaniel.

As chairwoman of the Seeworth board, Swinton spoke to the OKCPD officer assigned to investigate the school in April 2019. The officer wrote that, “Swinton stated she had looked into the matter and failed to see any criminal misconduct.” Around the same time, a human resources professional named Greg Dewey was voted off the board in what he described as a “30-second meeting” after he questioned Swinton’s response to a whistleblower letter alleging criminal conduct by Grigg.

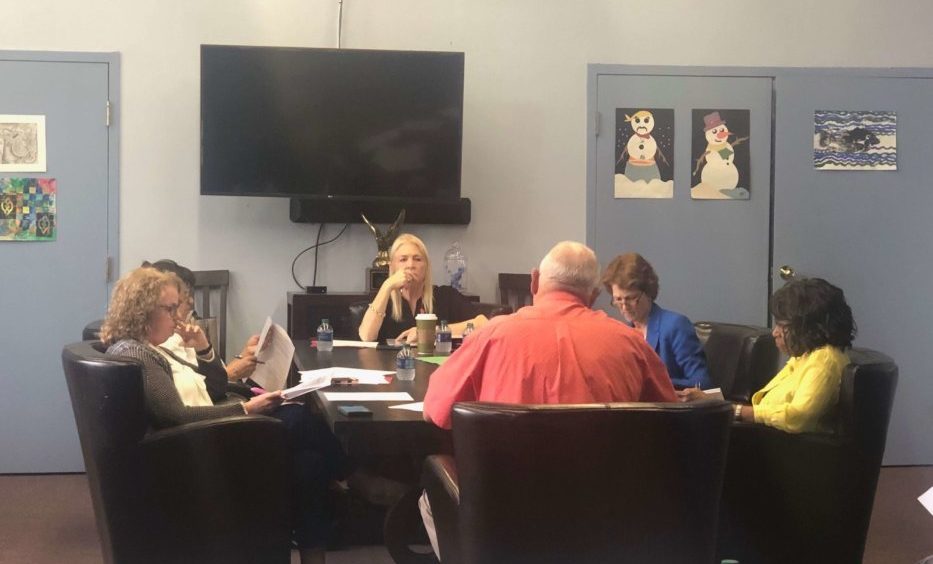

Two months later, however, the smoke around Seeworth Academy’s financial management had become a fire. Grigg was terminated, and the board voted to relinquish its charter from OKCPS and dissolve the school. At a June 14 board meeting, a woman identifying herself as a volunteer initially denied a NonDoc reporter access to the meeting room. During the meeting, a consultant reminded board members of various Open Meeting Act requirements.

Auditors discovered that the school lacked a number of required records related to board meetings, and people interviewed for the audit relayed stories of the board not complying with the Open Meeting Act.

“There were numerous instances where neither Grigg nor the staff had been approved for a bonus by the board but Grigg still ordered bonuses to be paid,” auditors wrote. “In violation of the Open Meeting Act, director bonuses were not included on board agendas before being discussed and approved in the board minutes.”

But actions of the board after Seeworth officially closed June 30, 2019, also may have violated the law. Auditors discovered that the board held four meetings between July 2 and Sept. 16 and “continued to expend Seeworth resources in their pursuit of keeping Seeworth open.”

In July and August, Seeworth board members refused to relinquish school property and funds to OKCPS. The district took the Seeworth board to court, which resulted in an order directing Seeworth board members to turn over property and funds to OKCPS. (The district repossessed a GMC Yukon from Grigg’s home because it was school property.)

During that time, the Seeworth board made “improper expenditures” of more than $81,700 for payroll and benefits, more than $44,700 for legal services and more than $9,200 for operations of the closed school, according to auditors. Auditors identified 114 expenditures made after the school closed June 30.

“Of these 114 expenditures, 96 expenditures totaling $135,713.98 were for services incurred or items purchased after June 30, 2019, and deemed inappropriate expenditures,” auditors wrote. “Statute defines that school funds may only be used for their defined purpose. These funds were apportioned for the use of Seeworth which ceased to exist on June 30, 2019.”

Auditors took specific issue with an Aug. 29, 2019, check that paid more than $57,700 from Seeworth’s General Fund to the prominent education law firm Rosenstein, Fist & Ringold.

“At the time the cashier’s check was issued, only one invoice, totaling $12,988.50, had been incurred for services performed prior to June 30, 2019,” auditors wrote. “The remainder, totaling $44,753.99, was used by RF&R for services incurred and billed post June 30.”

Auditors wrote that “some legal expenses included in the $44,753.99 considered improper could have been incurred for pre-June 30 related services,” but they said “RF&R only provided partially redacted invoices for our review.”

“Based on these invoices it was not possible to fully ascertain how much of the services billed by RF&R were for pre-June 30 associated costs,” auditors wrote, noting that RF&R had invoiced Seeworth eight times between July 2019 and May 2020 for work that included advice on subleasing property, a rejected memorandum of understanding between Seeworth and OKCPS, and representation of Seeworth in court against OKCPS.

“Neither (interim Superintendent Sherry) Kishore, Swinton, nor Wilson could provide an explanation for the amount of the check, $57,742.49,” auditors wrote. “RF&R was also unable to provide an explanation as to how the amount of the cashier’s check related to any outstanding billings or invoices.”

Auditors wrote that “RF&R continued to apply invoices against the remaining balance of $44,753.99 through April 2020.”

“At that time,” auditors wrote,” the residual of $4,144.09 was transferred to the law firm of White and Weddle, P.C.”

Floyd on attorney payments: ‘I just don’t know’

Chronicling what happened to that remaining $4,144.09 in Seeworth funds was not the only time state auditors would encounter the law firm of White & Weddle during their investigation.

Attorney Joe White accompanied former Seeworth board members Floyd, Swinton and Wilson — each an attorney herself — during their 2021 interviews with state auditors Brenda Holt and Rainer Stachowitz. White asked auditors questions about their investigation prior to the interviews with Wilson, Swinton and Floyd.

“He described himself more as a facilitator of these interviews than an attorney,” auditors wrote of White, “but he agreed that Swinton would say that he was their attorney.”

Floyd was the final former Seeworth board member to answer auditors’ questions, and her interview summary noted that Holt left five messages for Floyd trying to schedule an interview in February 2021. In April, Floyd called Holt back and downplayed her role with the school, despite serving on its governing board for nearly two decades.

“[Floyd] acknowledged we need to interview her but suggested that she wasn’t that involved in the school’s business because she was so busy with her senator responsibilities,” the interview summary states. “She suggested that other board members would probably be more apt to answer any questions we had.”

RELATED

Seeworth audit finds ‘fraud’ by superintendent, inaction by powerful board members by Tres Savage

On April 29, 2021, auditors received a letter from Floyd on Oklahoma State Senate stationary saying she believed auditors would send her written questions to answer instead of meeting for an interview.

“While I understand meeting in-person is optimal, I appreciate your willingness to work with me since we are currently in session,” Floyd wrote on a Thursday. (The Legislature typically does not meet for session on Fridays.)

About 10 days after the Legislature adjourned its 2021 session, Holt and Stachowitz ultimately met June 7 with Floyd and Joe White, the attorney whose law firm received the remaining $4,144.09 of Seeworth funds.

Asked in April 2022 about White’s representation of herself, Swinton and Wilson during their state auditor interviews, Floyd told NonDoc, “There was no representation.”

“He was just there as consulting,” Floyd said, adding that White was not paid for his time with her during the auditors’ interview. “I asked him to bill me. He said, ‘No, I’m doing this pro-bono.'”

But during Floyd’s interview with state auditors, White indicated that he would be paid for his time when the conversation turned to the differences between incremental billing and block billing in the legal profession. White said he bills in blocks, not increments.

“I track it,” White said. “But instead of having .10 (hours), .05, I will bill — like, I know that from one o’clock today until 1:50 I was with you all. I know that from 2:15 until we quit this, I was with you all. I will bill that as one bill. I won’t say ‘one to 1:50.'”

Holt, one of the state auditors, asked Floyd and White why Seeworth funds were sent to Rosenstein, Fist & Ringold and then to White’s law firm after the school had closed.

White said the $4,144 provided to his firm ultimately paid for him defending federal discrimination lawsuits filed in April 2020 by terminated Seeworth employees Sharilynn Rodgers and Tarrence Rodgers. Both of the suits were withdrawn.

Holt said school money should not have been used to pay attorneys for work performed after Seeworth closed.

“Well, who the hell is going to represent Seeworth in federal court?” White replied.

Holt said, “I don’t know.”

“I know work was done, and I got under paid,” White said, drawing laughter from the other auditor, Stachowitz. “I mean, I’m doing the lord’s work today.”

Asked about Seeworth’s lump-sum payment to the law firm of Rosenstein, Fist & Ringold — and the transfer of remaining funds to White & Weddle — Floyd told NonDoc she had no knowledge of the details.

“The treasurer would have handled that, I don’t know. I just don’t know,” Floyd said. “We went and closed everything out, and I thought everything was closed out.”

Floyd offered a similar statement to state auditors, according to audio of her interview. When auditors asked if she was aware of school expenditures after the school closed June 30, Floyd answered, “No.” Auditors then asked if the expenditures were discussed at the subsequent board meetings, but Floyd did not respond. Upon further questioning, she outlined what she recalled from those meetings.

“There was discussion as to wrapping everything up and what bills we had outstanding,” Floyd told auditors. “Were we going to have enough money to pay everything, and just making sure that everything was done.”

On July 20, White returned a phone call from NonDoc regarding the Seeworth investigation, and he described his professional engagement with Floyd, Swinton and Wilson as having “assisted in the facilitation of information with the state auditor for those three.”

Asked if the $4,144 of Seeworth money covered his engagement with the board members, White replied: “I can’t speak to what has been paid. I can speak to that money still sitting in my trust account. Every penny.”

Asked additional questions about the Seeworth money and his engagement with the former board members, White became irritated that he was being asked questions on the record and hung up the phone.

Follow @NonDocMedia on:

‘Listen to me or read about it in the paper’

State auditor interviews with Floyd’s fellow long-time board members — attorney Lee Anne Wilson and Judge Barbara Swinton — featured similar discussions of Grigg’s alleged embezzlement, the decision to close Seeworth and the financial encumbrances made after the school closed.

But auditors also asked Wilson and Swinton about Seeworth’s 2008-2009 internal audit that had been performed and presented to the board by Kerry John Patten, CPA. In his audit, Patten reported three “significant deficiencies in internal control over financial reporting” that he considered to be “material weaknesses” for Seeworth Academy:

- A lack of internal controls for accounting, paying and reporting functions of payroll and benefits that “greatly increases the potential for fraudulent/illegal activities and/or unauthorized payment for salary/benefits”;

- Issues regarding a Talihina resident named Don Guthrie being employed by Seeworth for accounting services and being “the individual who designed and owns the accounting software the academy is using to support their accounting records and provide their accounting reports.” Patten wrote that Guthrie “has total control over the accounting system and performs payroll and expenditure functions for the academy”;

- Inadequate segregation of duties “to ensure that duties assigned to individuals are done so in a manner that would not allow one individual to control both the recording function and the procedures relative to processing a transaction.”

For their 2021 investigation, state auditors interviewed Patten more than a decade after he audited Seeworth’s finances and presented the school’s board with the “material weaknesses.” On March 6, 2021, Patten signed an affidavit for state auditors that outlined what he said happened when he presented his 2008-2009 audit findings to the Seeworth board:

I discussed the management letter and the audit comments with the board.

The entire time I was at this meeting it seemed tense to me and after I began presenting, one of the board members said something to the effect of “Do we have to listen to this?” I replied that they could either listen to me or read about it in the paper. They listened after that but argued every point.

When I left the meeting, I did not feel like I had helped that school at all and that none of my recommendations were likely to be implemented.

Patten’s 2008-2009 audit revealed that Grigg, the longtime Seeworth superintendent, had paid more than $8,300 of her personal home mortgage from Seeworth funds. (State auditors said Grigg declined to be interviewed on the advice of her attorney.)

In her February 2021 interview with state auditors, board member Lee Anne Wilson said she did not recall Patten’s audit presentation “because it occurred 11 years ago,” according to the auditors’ interview summary.

“Wilson stated that Grigg did a great job and that some of the things that occurred in the last couple of years were clearly an anomaly,” the interview summary stated. “Wilson thought [Grigg] had a lot of power but not an inordinate amount.”

State auditors also asked Swinton about the 2008-2009 audit being presented to the board.

“Swinton stated that she did not recall anything like a board member saying something like do we have to listen to this,” the interview summary stated. “[Swinton said board members] were very respectful and understood the importance… When [state auditor Rainer Stachowitz] asked whether she remembered the meeting she stated ‘no.'”

During her interview with state auditors, Swinton discussed her conversations with law enforcement officers beginning in 2019.

“Swinton initially seemed agreeable to scheduling an in-person interview, but then hesitated stating ‘the U.S. Attorney’s Office was probing the practices of Janet Grigg’ and because of that she would probably need to contact ‘our attorney’ to see if she should speak with anyone on the subject,” auditors wrote near the top of their interview summary. “[We] inquired as to what U.S. Attorney was working the case and if this was the Western District of Oklahoma, she said ‘yes.’ Swinton did not provide any U.S. attorney name but stated that Sean Querry was the investigator.”

State auditors noted that Querry is an Oklahoma City Police Department officer who had documented the initial embezzlement complaint in April 2019. In his police report, Querry wrote that Swinton initially told him “she had looked into the matter and failed to see any criminal misconduct.” He wrote that, four months later, Swinton contacted him again to say at least one questionable transaction had been identified.

OKCPD officer Sean Querry has been a member of a U.S. Secret Service White-Collar Crime Task Force.

Asked if he has been coordinating his criminal investigation and charging decisions about Seeworth Academy with federal law enforcement officials, Prater declined to comment.