Last week, officials from the U.S. Department of Justice visited the Oklahoma County jail for three days. Not long after, on Sunday, July 31, an inmate died at the jail — the 12th fatality this year.

The facility has effectively been under federal oversight since 2009, when jail authorities and the DOJ entered into a memorandum of understanding to address ongoing civil rights concerns at the jail. According to the terms of the MOU, the detention center could even be subject to complete federal takeover if standards are not met.

There were 14 deaths at the jail in 2021, according to Oklahoma State Department of Health Commissioner Keith Reed. With five months left in 2022, this year’s current total of 12 is likely to grow.

Nonetheless, on Monday, at a monthly meeting of the jail trust, which oversees the facility, attorney Paula Williams painted an optimistic picture of the DOJ visit.

“The Department of Justice was on site for about three days, and they brought several experts in the mental health field, medical field and in detention facilities,” said Williams, who serves as outside counsel for the trust. “I wanted to share first that they did have praise for the jail administration and leadership that is currently there. One expert, Dr. Kenneth Ray, called the administration a competent and motivated leadership team.”

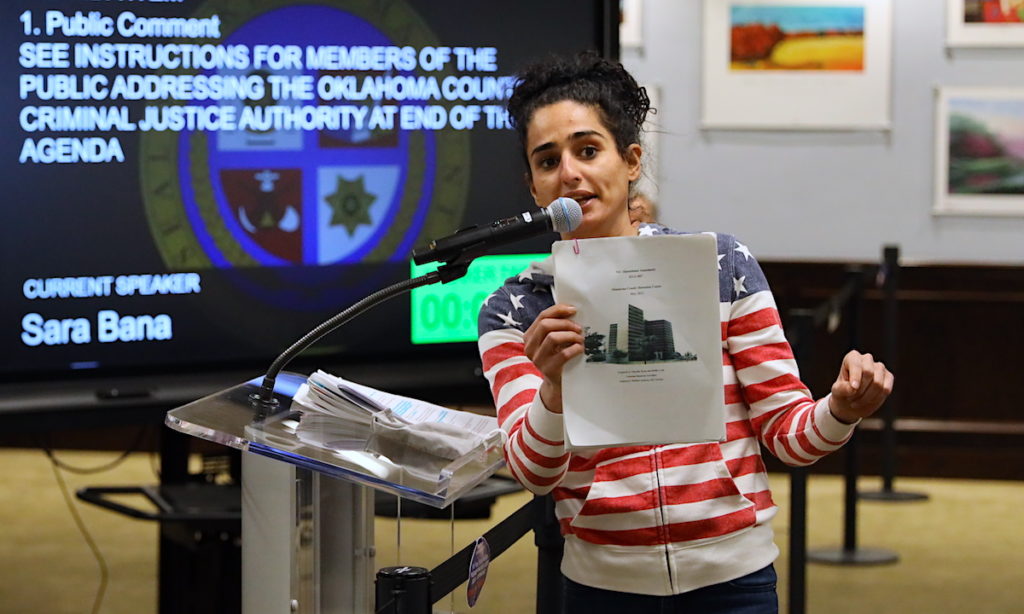

The latter part of her remarks drew jeers from members of the People’s Council for Justice Reform, a local activist group whose members frequently speak at jail trust meetings. During the public comment portion of Monday’s meeting, group member Christopher Johnston called for a federal takeover of the jail.

“We lost another human being. That’s 12 in seven months,” Johnston said. “We’re en route to losing 20 to 24 this year. Management. It’s people. There’s just too much evidence against you guys. It’s time that we start doing something about this issue and stop bullshitting.”

In the June 28 election, Oklahoma County voters approved funding to build a new jail, but that new facility is still years away from being a reality. In the meantime, the current building and its management remain beset by the problems that prompted the need for a new jail in the first place. Inmate deaths continue to mount, and calls for better oversight continue to grow louder from activists and officials alike.

Death by death in 2022

The first of the dozen deaths to occur in the Oklahoma County Jail this year happened in the second week of January, and the jail has averaged 1.7 deaths per month through July.

Because the Oklahoma County Jail’s design doesn’t allow for direct supervision of inmates at all times by staff, they are monitored remotely by video cameras and during regular rounds through the facility. Many of the dead were discovered unresponsive by staff making routine rounds.

Oklahoma County Jail deaths this year include the following:

- On July 31, the jail announced the death of Robert Dale Richards, 50. Richards was found unresponsive in his cell by staff distributing medicine. He had been booked on June 28;

- Shawn Slavens was one month shy of his 46th birthday when staff responded to a fight inside a cell on June 25. Slavens was found unconscious and taken to a hospital. He died from his injuries July 11;

- On July 2, Corey McMichael died at an OKC hospital after being transported there from the jail’s medical unit because he was experiencing “health related issues.” McMichael, 46, had been in the jail since Aug. 7 of last year;

- Inmate Melvin Loveless, 44, died by suicide in his cell on June 22 and was found by staff. Loveless had been booked into the jail on June 12;

- In the early morning hours of June 9, staff passing out breakfasts found an un-named man unresponsive in his cell after an apparent suicide. At the request of his family, the man’s name was not released to public;

- On May 13, staff discovered Eddie Garcia, 25, unresponsive in his cell at about 2 a.m. He was taken to a hospital where he was pronounced dead. Garcia had been booked into the jail on March 21;

- Detention center staff found Dustin Revas, 26, unresponsive in his cell at about 2 a.m. on March 28. A cellmate told staff Revas had been in digestive distress but refused to alert staff in the hours before his death. He had been booked March 23;

- On the evening of March 11, jail staff found Charles Moore, 48, unresponsive in his cell while passing out medication. Despite efforts by staff to revive him, Moore was pronounced dead. He had been booked on March 9 and was being held in a new-arrival pod at the jail;

- Andrew Avelar, 27, was booked into the jail Jan. 31. He was found Feb. 26 unresponsive in his cell by staff doing routine checks. An initial investigation found Avelar may have died from a suicide.

- Winfred Lowe, 57, was found unresponsive in his cell by staff dispensing medication on Jan. 17. He had been booked into the jail March 30, 2021. Lowe spent 100 days in a hospital while in custody of the jail;

- Austin Bishop, 30, died in the jail Jan. 12 after detention officers were alerted to a medical emergency while they were serving breakfast. Bishop had been booked in June 6, 2021.

Jail administrator Greg Williams, who was hired by the trust to run the jail when it took over the facility from the sheriff in 2020, said in a statement to NonDoc that jail staff continue to work to reduce inmate deaths.

“We mourn any loss of life and always seek to protect the lives of our detainees and staff,” Williams said. “Due to pre-existing medical issues, some deaths are unrelated to a detainee’s time in our facility. Others die by suicide or overdose, which is often due to contraband entering the facility. Our fight against contraband is multifaceted and ever-evolving. Along with our new body scanner, we’ve modernized intake procedures to better spot contraband. Changes in our intake process also help identify individuals who are in need of medical or mental health care. We work closely with our medical provider to identify detainees with severe physical and mental health issues, and alert the courts to help facilitate their release when appropriate.”

Suicide leading cause of death in jails

There are about 547,000 people housed inside America’s city and county jails, and, while most of them leave those facilities alive, some do not.

According to data compiled by Prison Policy Initiative, from 2000 to 2018, suicide was the leading cause of deaths for those incarcerated in city and county jails, accounting for around 30 percent of deaths. An incarcerated person is three times more likely to attempt suicide than someone on the outside.

Among those who die in jail by suicide, the median time from booking to death was just nine days, according to the data compiled by Prison Policy Initiative. For drug overdoses, the median time is one day, and for inmates murdered by other inmates, the median time is 29 days from booking to death.

Women typically have a 7 percent higher mortality rate than men while incarcerated in city and county jails.

And health care inside jails can vary widely. According to a report by Reuters, which analyzed data from the top five leading providers of jail health care services in the country, jails that contracted with outside vendors to provide health care typically had a higher mortality rate than those with services managed in-house. The death rates were “18 to 58 percent higher, depending upon the company.”

The Oklahoma County Jail contracts with Turn Key Health for its medical services. Turn Key Health was not among the companies examined in the Reuter’s report, and the company has previously threatened to terminate its contract with the Oklahoma County jail trust if staffing levels were not improved.

The Oklahoma County Jail’s design has also been cited as a flaw. The medical unit is located on the 13th floor, a fact that can be problematic in an emergency because of the need to use elevators to get to the ground level from the top floor. An inspection report from the National Institute of Corrections also found phones that were not working in the medical unit. The report states:

For example, the phones on the 13th floor pregnant inmate unit, the [inspectors] asked the inmates to conduct a system test explaining that it was the middle of the night and their cellmate had gone into labor. She attempted two numbers that she had been told to use to no avail and then was advised of a third. Apparently, the third went to central control but was unanswered.

Oklahoma County Jail death rate is high

There were 73 deaths at the Oklahoma County Jail from 2000 to 2019, according to data gathered by Oklahoma Watch and Reuters. During that same time period, the Tulsa County Jail saw 34 inmate deaths, while Cleveland County recorded seven deaths.

The frequency of deaths at the jail has been particularly high in the past couple of years. The Oklahoma County Jail saw four deaths in 2020, according to The Frontier, and six in 2019. In the 19 months since January 2021, records indicate 26 inmates have died — more than one-third of the total from the 10 previous years.

Even before the jail trust took over the jail, in July 2020, Oklahoma County was well ahead of the national average for jail deaths. Between 2016 and 2019, the jail’s mortality rate was 4.77 deaths per 1,000 inmates. The national average was 1.46 over that period, according to data compiled by Oklahoma Watch.

That fatality rate is likely significantly higher now, given the spate of recent deaths.

District 2 County Commissioner Brian Maughan said that while it’s important to take each death seriously, there are a variety of factors that contribute to fatalities.

“There are always ebbs and flows,” Maughan said. “Some years it is higher than others. We always take it seriously when people die in our jail. I don’t know anyone involved that takes that lightly. But there are some circumstances behind some of the people that come into the jail who are absolutely determined to harm themselves, and if someone is that determined, it is very hard to prevent that.”

Echoing Williams, Maughan said many of the current deaths are related to drug overdoses, particularly from fentanyl. Asked whether jail staff could do more to prevent drug-related deaths, Maughan said the problem is not unique to Oklahoma County.

“We’re dealing with a fentanyl epidemic that has exploded nationally, and we have seen the impact here,” he said. “It’s fatal if even small amounts are consumed. I don’t think it’s a case of dirty or bad detention officers — it’s a huge problem nationally.”

Prater: ‘I believe it’s a culture issue and not just the facility’

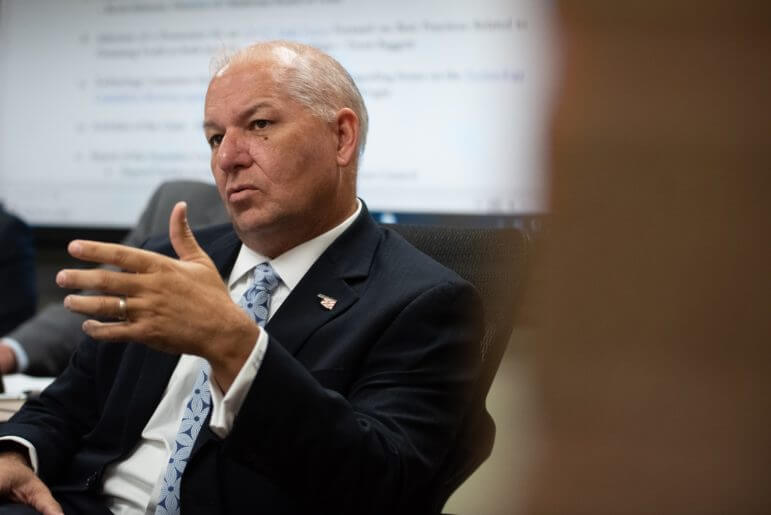

Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater is one county official who has little faith in Greg Williams or the jail trust. In 2021, Prater received permission to impanel a grand jury to investigate, among other things, “lethal uncorrected mismanagement” of the Oklahoma County Jail under the supervision of the jail trust. Prater later recused himself from that investigation.

“There are members of the trust who are county officers who are advised and represented by our office at times,” Prater told The Oklahoman’s Nolan Clay. “They raised concerns regarding conflicts of interest. And to avoid any appearance of impropriety, I voluntarily disqualified our office.”

The grand jury investigation is currently being handled by District 27 District Attorney Jack Thorp. The outcome of Thorp’s multi-county grand jury investigation remains unknown, but criminal indictments for those involved in the jail’s operation and management could be possible.

Though not involved in the investigation, Prater continues to be shocked by the number of deaths at the jail.

“To say I’m concerned or to say it’s concerning — that just sounds like I’m minimizing it,” Prater said. “That’s not even a strong enough description of how I feel. I’m sick and tired of the jail trust not ensuring people are well cared for at the jail. I’m sick and tired of it is the best way I can put it.”

Prater said he’s hopeful that Thorp’s investigation will lead to fewer deaths and dangerous situations at the jail, and he added that he doesn’t think the planned new jail will necessarily solve the entire problem.

“I believe it’s a culture issue and not just the facility,” Prater said. “They are chronically understaffed, and I believe the trust has been dishonest about their staffing levels. I think that’s led to the increased number of inmates who are dying.”

Prater said the number of deaths at the jail since the trust took over in 2020 is unprecedented in his eyes.

“I haven’t researched every jail in the country, but in talking to people who have come in to look at our jail and who have tried to improve it, it’s one of the worst jails in the country as far as inmate deaths,” Prater said. “In my experience, in this office for 16 years, I’ve never seen anything like it in my life.”

Thorp did not return calls from NonDoc regarding the current status of his investigation.

Deaths, injury costs add up for county

On July 5, jail administrator Greg Williams presented the jail trust with his monthly report. Williams began his remarks by mentioning that there had been three deaths at the jail since they trust last met.

No member of the trust questioned Williams on the circumstances of the deaths. Chairman Jim Couch simply thanked him for the report and moved that it be accepted by the trust.

But what the trust talks about behind closed doors in executive session is another matter. According to District 3 County Commissioner and trust member Kevin Calvey, those conversations are more interesting than what the public sees.

“We had several lawsuits against the county for things involved in the jail. It’s actually worse than has been out in public,” Calvey, who is running for district attorney, said during a debate hosted by NonDoc in June “As I said, the former sheriff was not at all transparent. The current jail trust is transparent. That’s why you hear more things now than in the past. There were situations in which inmates were abused. In some cases, there were prosecutions of jail staff, and I will point out that is a small minority of people that work at the jail.”

Most recently, Oklahoma County settled a lawsuit with the estate of Charlton Chrisman, who died in 2017 after officers shot pepper balls at him from close range. That suit cost the county $1.1 million.

Last year, four former inmates sued the jail following a 2019 incident in which they were forced to listen to the song Baby Shark on a loop for hours.

Both of those incidents happened while the jail was still being operated by the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Department, but there are lawsuits related to more recent incidents in the pipeline.

Among the items discussed in executive session during the jail trust’s April meeting were wrongful-death tort claims from the estates of Parker James Stephens and Gregory Davis. Both died in the jail last year.

Stephens, 21, was found dead from suicide inside the jail in early 2021. His family had repeatedly contacted the jail’s administrative staff about his mental state in the months prior to his death, according to a report by The Frontier.

And deaths are not the only causes of lawsuits. Earlier this summer, an inmate sued the county and jail trust over bed bugs. Another inmate is suing after he was stabbed earlier this year, something the inmate said happened because he was not adequately protected by staff.

District 1 Commissioner Carrie Blumert said making the jail a better place was among her biggest priorities when she first ran for the commission, in 2018. But Blumert, who is facing Anastasia Pittman in a runoff for the District 1 seat later this month, said she has less input over the jail than she did before the trust took over.

“Every time I’m notified of a death at the jail, my heart sinks,” Blumert said. “When the sheriff had the jail, we as commissioners had a little more interaction. After a death, I’d call the sheriff and go over what happened. I can stay connected with Loretta (Radford), who I appointed as my member to the trust, but I don’t have a lot of authority over telling them how to run the jail.”

Blumert said it’s not uncommon for the county to face lawsuits filed by the relatives of those who have died at the jail, or inmates who have been injured there. Blumert said the recent $1.1 million settlement was the largest she can recall since she was elected.

“Typically when someone dies in the jail, family members will seek litigation, which is completely their right,” Blumert said. “What that does for the county is we typically have to hire outside counsel, and if we have to settle a case, which we sometimes do, we are spending tax dollars on that when we are found liable.”

(Correction: This article was updated at 8 p.m. Thursday, Aug. 4, to correct the age of Andrew Avelar. NonDoc regrets the error.)